Classical Chinese Literature of the Ming and Qing

BackClassical Chinese Literature of the Ming and Qing

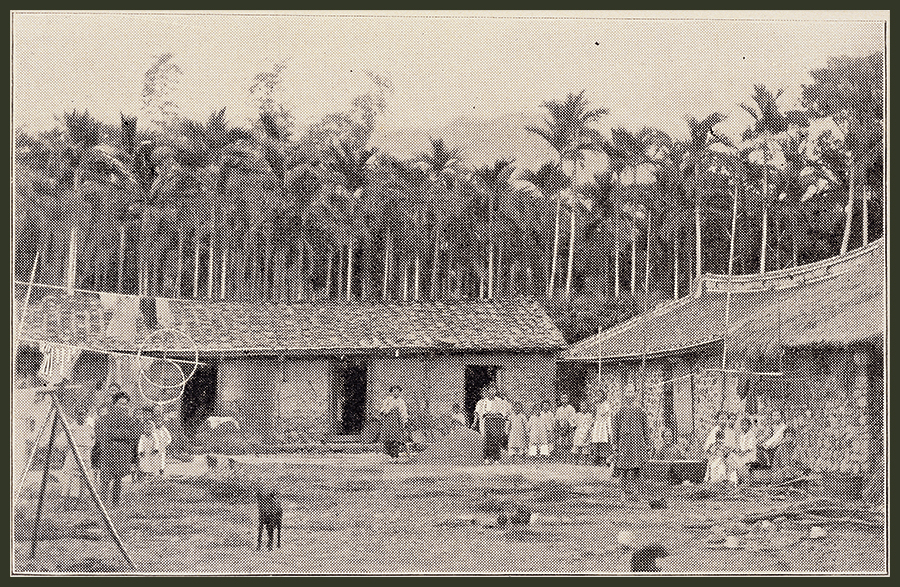

Caption: Han Chinese village in eastern Taiwan. Collection of the National Central Library.

Although classical Taiwanese literature originated in China, when it is viewed in the context of the history of Chinese literature—which covers a vast geographical expanse and has lasted for thousands of years, the classical literature that was created on the tiny island of Taiwan and has a history of less than 400 years is treated as nonexistent or unworthy of mention. But when one views it from the perspective of Taiwan, one judges the significance and value of classical Taiwanese literature differently.

The peak of classical Taiwanese literature, in respect of artistic achievement and depth of thought, came during the Japanese colonial period (1895–1945), i.e. the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was the culmination of 200 years’ accretion and deepening of Han Chinese culture in Taiwan. The development of classical literature in the Chinese language during the Ming and Qing dynasties in Taiwan, over more than two centuries, was a process of transplantation and then naturalization. In his Zhuzhici (Bamboo Branch Ballads), Qiu Fengjia describes how Chinese immigrants from Fujian and Guangdong settled in Taiwan and gradually took root over 200 years. In fact, Qiu’s words are also an apt portrayal of how classical Chinese-language literature developed in Taiwan.

Before Han Chinese settlers arrived in Taiwan, this island was already inhabited by many aboriginal tribes who transmitted culture through oral traditions rather than written records. The first text-based literary work in Taiwan emerged in the mid-17th century, as the Ming dynasty was collapsing. Shen Guangwen, who arrived in Taiwan before Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong), was credited as the first person to bring Han Chinese culture and literature to Taiwan, and thus hailed as the founder of Taiwanese literature. A group of literati including Wang Zhongxiao and Xu Fuyuan arrived in Taiwan later with Koxinga. This group mostly wrote strongly nostalgic poems evoking the pain of losing their country, but they also wrote about the scenery and customs of Taiwan and praised the beauty of the island. This was the first “loyalist literature” in the history of Taiwanese literature. Zheng Jing, Koxinga’s son, also left behind a poetry collection known as Dongbilou Ji (Collection of the Dongbi Pavilion) under the alias Qianyuan Zhuren (Master of the Qian Garden).

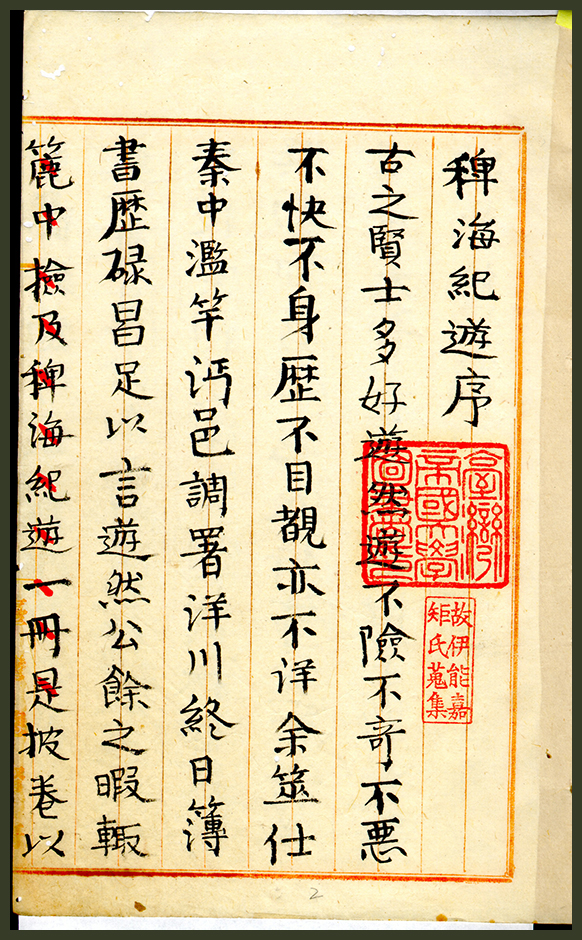

Following the fall of the Zheng regime founded by Koxinga, Taiwan came under the control of the Qing Empire for over two centuries, from 1683 to 1895. Between the late 17th and the mid-18th century, roughly between the reigns of the Kangxi and the Jiaqing Emperors, classical literature in Taiwan was mostly authored by government officials posted to the island from China and a small number of Chinese travelers. Their stay in Taiwan tended to be of short duration; their writings, laden with curiosity and exoticisms, were observations on Taiwanese landscapes and customs, including the geography, climate, agricultural produce, and plains-aboriginal culture. Representative works from this period include Rongzhou Wengao (Manuscripts of Rongzhou) of 1684, written by Ji Qiguang, county magistrate of Zhuluo; Pihai Jiyou (Small Sea Travel Diaries) of 1697 by Yu Yonghe, who came to Taiwan to mine sulfur; Chikanji (Chikan Collections) of 1705, written by Sun Yuanheng, sub-prefect of Taiwan; Dongzhengji (Collection on the Campaign to the East) of 1721 by Lan Dingyuan, who arrived in Taiwan with Lan Tingzhen to quell the Zhu Yigui Uprising; and Taihai Shicha Lu (Records from the Mission to Taiwan and its Strait) by Huang Shujing.

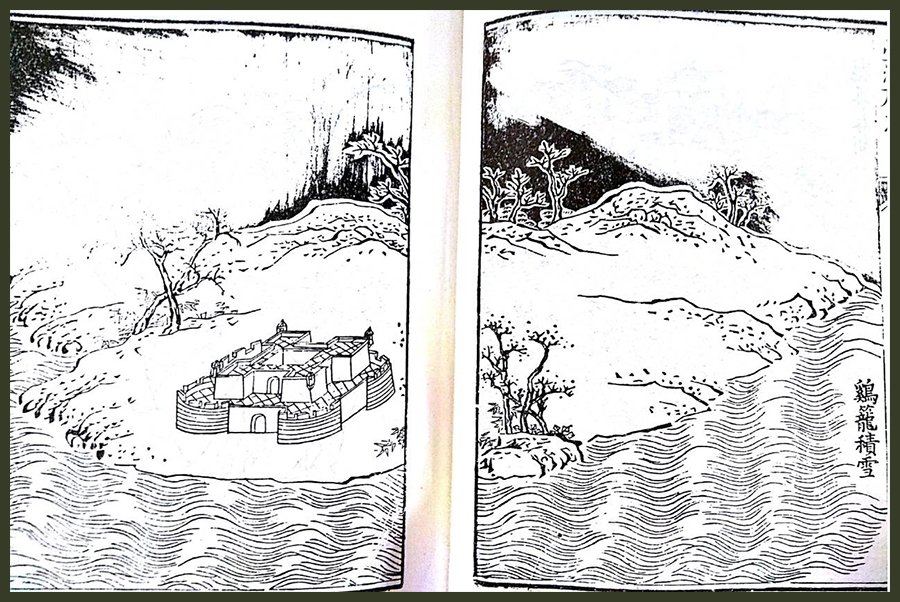

Ji Qiguang and Shen Guangwen founded the Dongyin Poetry Society, the first classical poetry society in Taiwan. Yu Yonghe’s three-volume Pihai Jiyou records his voyage across the sea to Taiwan, what he saw on his way north from Tainan to Taipei, and his mining sulfur in Beitou. With its vivid writing, this first Taiwan travelogue has been highly regarded by posterity. Sun Yuanheng’s acclaimed Chikanji is a collection of poems depicting the landscape and customs of Taiwan and Sun’s experience as an official here. In addition to these works, gazetteers also collected numerous poems about the “Eight Views of Taiwan”, a unique genre in Taiwanese classical poetry.

In addition to poetry and prose, there was also a third genre called fu, or rhymed prose. This genre lends itself well to encomia and has been popular in China since the Han dynasty. The fu on Taiwan written by literati such as Lin Qianguang, Gao Gongqian, and Wang Bichang often use flowery language and exaggerated brushstrokes to praise the beautiful scenery of Taiwan and tout the Qing Empire’s rule, so they are highly political works. Jiang Risheng’s Taiwan Waiji (A Supplementary History of Taiwan), which blends history and novel, records the stories of the four generations of the Koxinga family.

Caption: Pihai Jiyou (manuscript by Inō Kanori). Collection of the National Taiwan University Library.

Caption: “Snow in Keelung”, part of the Eight Views of Taiwan. Taiwanfuzhi (Taiwan Prefecture Gazetteer).

The Qing Empire’s rule over Taiwan was consolidated during the Qianlong and the Jiaqing reigns. Meanwhile, through the mechanism of the imperial examination a Taiwanese scholar class gradually emerged. Important figures and works of the time include Bansongji (Collection of Bansong) written by Zhang Pu of Tainan; Beiguoyuan Quanji (Complete Collection of the Beiguo Garden) by Zhang Yongxi and Jingyuantang Shiwenchao (Jingyuan Hall Collection of Writings) by Zhang Yongjian, both from Hsinchu; Hainan Zazhu (Notes from Hainan) by Cai Tinglan of Penghu; Touxianlu (Records of a Moment of Leisure) and Taiguchao Lianji (Collection of Taiguchao) by Chen Weiying of Taipei; Cao Jing Shiwen Lueji (Short Collection of Cao Jing’s Poetry and Prose) by Cao Jing of Taipei; Shilanshanguan Yigao (Manuscripts of Shilanshanguan) by Shi Qiongfang of Tainan; Qianyuan Qinyucao (Poetry of the Qian Garden) by Lin Zhanmei of Hsinchu; Guanchaozhai Shiji (Poetry Collection of the Guanchao Studio) by Huang Jing of Guandu, Taipei; Xixing Yincao (Chanted Poems of the Westward Travel) by Li Wangyang of Yilan; and Taocun Shigao (Taocun’s Poetry Collection) by Chen Zhaoxing of Changhua.

As these writers were long settled in Taiwan, their works show a more sophisticated understanding of and deeper affinity for the Taiwanese land and people. Describing Taiwan’s natural landscape, war and conflict, idyllic home life, food and produce, and inter-ethnic interaction, the texts are often moving and show attention to detail, setting them far apart from outsider writings that tend to adopt an attitude of superiority and express a desire to enlighten the local populace.

Later, as the literary class continued to flourish, works of even higher quality were created by a new generation of writers known as the “Yiwei Generation” who were active between the end of Qing rule in Taiwan and the early days of the Japanese Colonial Period. When the island was ceded to Japan, some left Taiwan for China (e.g. Shi Shiji, Xu Nanying, and Qiu Fengjia), some initially went to China but later returned to Taiwan (e.g. Wang Song, Lin Chaosong, and Lin Yongchun), and others, such as Hong Qisheng, never left Taiwan. The works of this generation came to be regarded collectively as the second wave of “loyalist literature” in the history of classical literature in Taiwan.

What sets this wave apart from the first (under the Koxinga family regime) is that the literati were now faced with the aftermath of the crumbling of the Qing Empire—the collapse of feudal politics that had endured for thousands of years—as well as the introduction of Western philosophy of self-determination, technology, and civilization. As a result, classical Taiwanese literature of this period also underwent significant changes both in terms of the thought behind it and the language used.

(Left) Qiu Fengjia’s Litaishi (A Poem Upon Leaving Taiwan), calligraphy for Chen Yuncheng. Courtesy of the Cultural Affairs Department, New Taipei City Government.

(Right) Portrait of Lin Youchun. Courtesy of the National Tsing Hua University Library.

The classical Taiwanese literature of the Ming and Qing dynasties developed during a period that witnessed the fall of the Ming dynasty in the mid-17th century, the decline of the Qing Empire in the late 19th century, and the ceding of Taiwan to Japan after the Qing lost the First Sino-Japanese War. This period started in turmoil and ended in turmoil. As empires of both East and West scrambled for a piece of China, Taiwan, which is located between the continent and the great ocean, was also caught up in the turbulence. While classical Taiwanese literature during this period was still heavily influenced by its Chinese origin, gradually localization took place and developed a distinctively Taiwanese literary identity