Reconstruction and Anti-Communist Period

BackReconstruction and Anti-Communist Period

Caption: Ceremony to accept Japan’s surrender in Taiwan. Photo from Wikipedia Commons.

After Japan’s surrender in 1945, Taiwan came under the administration of the Republic of China. Henceforth, the course of Taiwanese literature split off from the new literature tradition born during the Japanese colonial era. During the early post-war period, people from Taiwanese and Chinese cultural circles met each other for the first time and came into close interaction. Between 1945 and 1949, a large number of journals were founded in Taiwan, drawing both Taiwanese and Chinese writers. Yiyang Zhoubao (Yiyang Weekly), set up by Yang Kui; the Japanese edition of Zhonghua Ribao (The China Daily News) edited by Long Yingzong; and Taiwan Wenhua (Taiwanese Culture), edited by Yang Yunping featured works of Taiwanese writers active during the Japanese colonial era and those of Chinese writers (e.g. Xu Shoushang and Tai Jingnong). The former sometimes discussed the history of new literature in pre-war Taiwan, while the latter might describe Chinese literature during the May Fourth Movement and the wartime.

Coming from different literary traditions and expressing different cultural identities, the two groups clashed in a debate on Taiwanese literature in Taiwan Xinshengbao (Taiwan Shin Sheng Daily News) between 1947 and 1949. Taiwanese writers emphasized their distinct literary tradition and consciousness, while Chinese writers traveling to Taiwan positioned Taiwanese literature as part of Chinese literature.

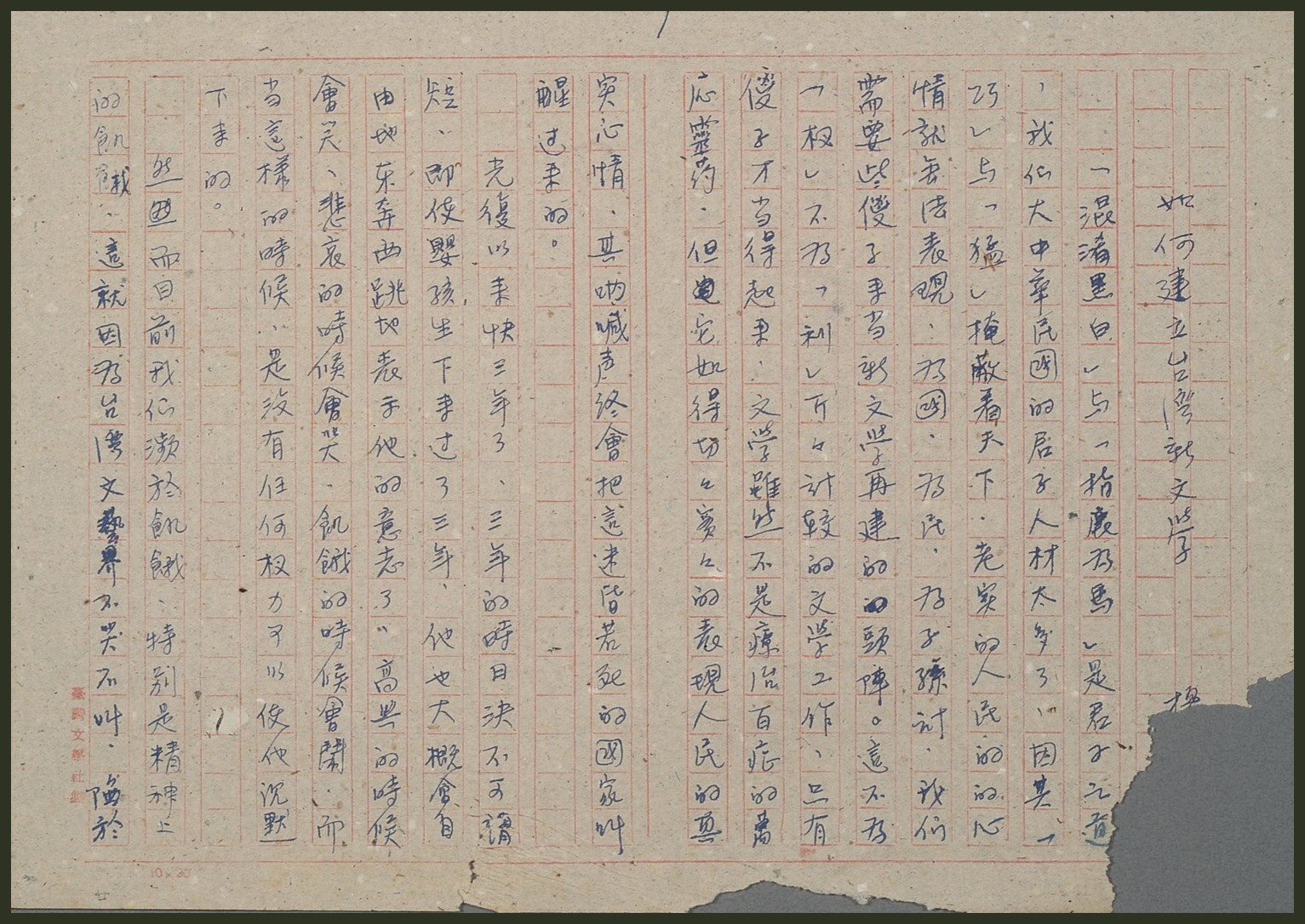

Caption: Manuscript of Yang Kui’s “Ruhe Jianli Taiwan Xinwenxue” (How to Create a New Taiwanese Literature). Collection of the National Museum of Taiwan Literature.

Two years after Taiwan came under the control of the Republic of China, a large-scale conflict between the Taiwanese and Chinese broke out, leading to the promulgation of a martial law order. In 1949, following the defeat of the Kuomintang (KMT) in the Chinese Civil War, the Republic of China government led by the KMT relocated to Taiwan, where it focused on preparations to take back China. In this tense political climate, the government also sought to use various cultural policies and organizations to control literary production.

From the end of the Second World War to the early 1950s, a series of political events (such as the February 28 Incident and the mass arrest of students on April 6, 1949) and cultural policies (such as the ban on the use of the Japanese language) meant that both Taiwanese writers and those newly arrived from elsewhere were subject to varying degree of suppression, and officially sanctioned works dominated the field. Nevertheless, many intellectuals continued to found publications and publishing houses for the sake of promoting literature and education, making the 1950s the second peak of new journals in the post-war period. With at least 60 publications circulating on the market, writers of different genres, many of them women, carved themselves a niche. The modernist and nativist literature that would come into prominence in the 1960s and 1970s can also be traced back to this period. The various literary movements are described briefly below.

Against the backdrop of the Cold War, anti-communism was the guiding ideology of the KMT and the US camp to which it belonged, as well as the highest principle for officially sanctioned literature. In 1953, Chiang Kai-shek wrote in “Minsheng Zhuyi Yule Liangpian Bushu” (On Nurture and Recreation) that the arts should promote the beautiful and pure national culture, and in 1955 he instructed that artistic productions should exhibit “fighting spirit.”

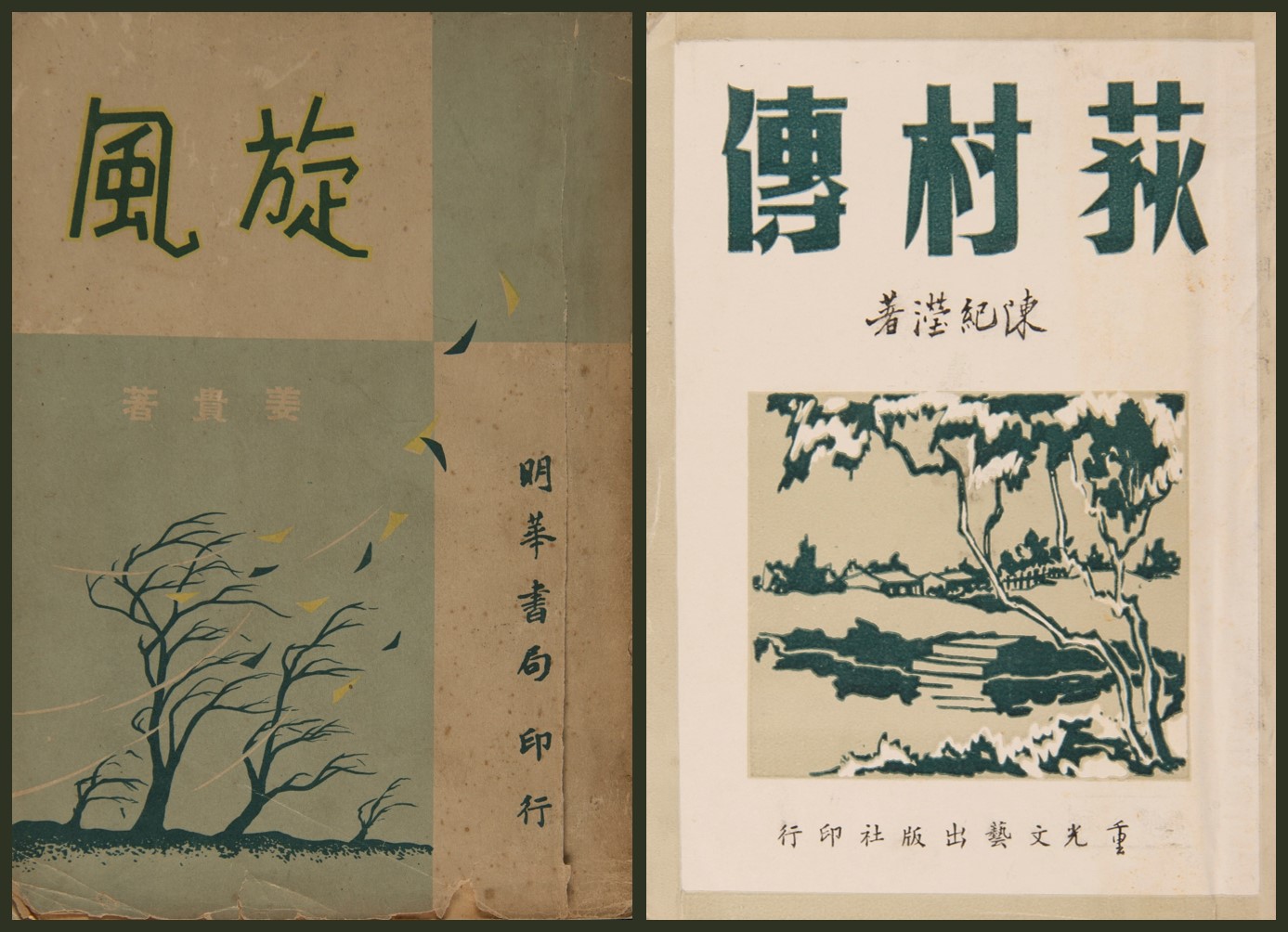

The government’s forceful promotion, coupled with the incentives of literary prize money and independent publication, created a phenomenon wherein the dominant literary works were either anti-communist literature that portrayed the inherent evil of the Chinese Communit Party, or nostalgic literature that lamented having left the Chinese homeland behind, or a combination of both. Chen Ji-ying’s Di Cun Zhuan (Fool in the Reeds), Pan Renmu’s Cousin Lianyi, and Jiang Gui’s Xuanfeng (Whirlwind) are some of the anti-communist works deemed to have high artistic value. Sima Zhongyuan established himself as a prominent writer of nostalgic literature with his Huangyuan (The Waste Land), which combined a Chinese epic narrative, Western stream-of-consciousness, and Japanese New Sensationalists. Zhu Xining shot to fame with the anti-communist novel Dahuoju De Ai (The Love of Big Torch) and subsequently published works of nostalgic literature Tiejiang (Molten Iron) and Hanba (Drought Demon) in the 1960s.

Left: Jiang Gui’s Xuanfeng (Whirlwind). Collection of the National Museum of Taiwan Literature.

Right: Chen Ji-ying’s Di Cun Zhuan (Fool in the Reeds). Collection of the National Museum of Taiwan Literature.

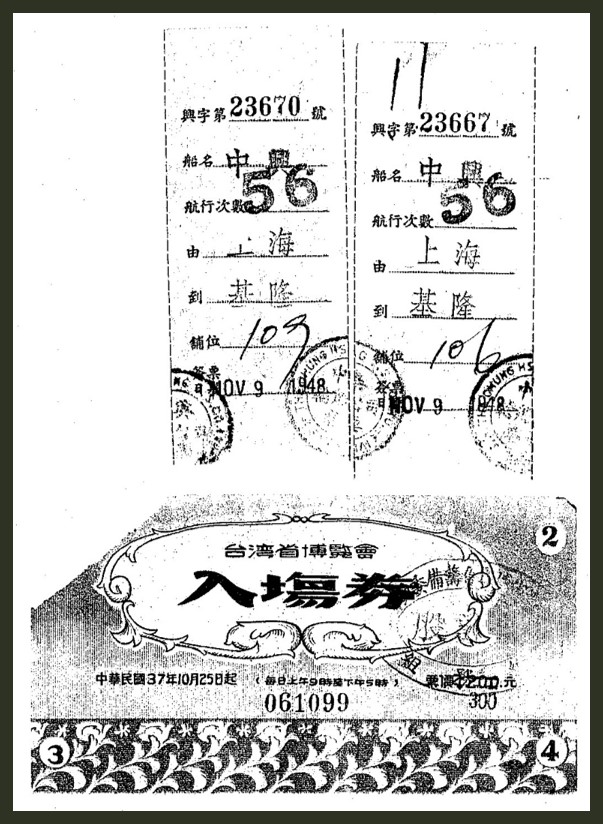

Caption: Lin Haiyin’s return steamer ticket. Collection of the National Museum of Taiwan Literature.

The mass exodus of Chinese in 1949 following the Chinese Civil War brought many highly educated women to Taiwan, leading to the first wave of women writers in the history of Taiwanese literature. While many women writers wrote along anti-communist and nostalgic lines, in accordance with government encouragement, as they became more experienced and confident, they also expanded their subject areas and started to move further away from officially sanctioned topics. Some works by female writers in this period already show gender awareness, while others wrote about Taiwan and expressed an intention to make this island their permanent home. For example, Lin Haiyin’s Hunyin De Gushi (Marriage Stories) and Luzao Yu Xiandan (Green Seaweed and Salted Eggs) explored in depth women’s status in love relationships and marriage amid social and cultural changes and in wartime. Guo Lianghui’s novels, mostly set in Taiwan, captured romantic relationships and gender relations in a changing society and urban women’s desires and struggles. Many female writers were also literary editors or publishers, such as Nie Hualing, under whose editorship Ziyou Zhongguo (Free China) magazine would only publish articles conforming to her dictum of “absolutely no clichéd anti-communist works.” The magazine was a liberal stalwart opposing authoritarian rule. Meanwhile, serving as editor-in-chief of the Lianhebao (United Daily News) literary supplement, Lin Haiyin focused on a “purely artistic” direction, giving space to nativist and modernist writers who at that time were on the fringe.

Left: Lin Haiyin’s Hunyin De Gushi (Marriage Stories). Collection of the National Chung Hsing University Library.

Right: Lin Haiying’s Luzao Yu Xiandan (Green Seaweed and Salted Eggs). Collection of the National Chung Hsing University Library.

Caption: Inaugural issue of the Ziyou Zhongguo (Free China) magazine. Collection of the National Museum of Taiwan Literature.

When the KMT government passed the ban on the use of Japanese, Taiwanese writers practically lost the ability to write. Chung Li-ho was one of the first Taiwanese writers to receive recognition because he was able to write in Chinese, having lived in China for many years when Taiwan was under Japanese colonial rule. In 1956, his novel Lishan Farm was awarded a prize by the Chinese Literature and Arts Award Committee. Some of Chung’s works are in the vein of nostalgic literature, describing his memories of living in China, while others are about the rural landscape of Taiwan; the narratives mix Chinese and Taiwanese dialects, like the nativist literature that would take off in the 1970s.

Wenyou Tongxun (Literary Friends Communications), founded in 1957, was a small-scale publication featuring the works of Taiwanese writers and information on their activities. Although it had only a small circulation, in a very difficult time it supported the literary activities of the first generation of post-war nativist writers including Zhong Zhaozheng, Chen Huoquan and Liao Qingxiu.

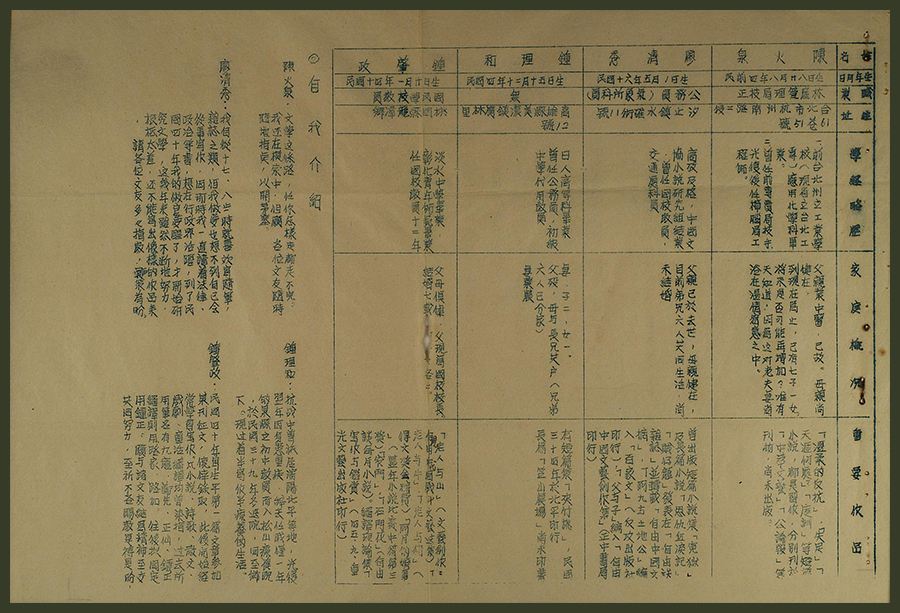

Caption: Short biographies and self-introductions by Chen Huoquan, Liao Qingxiu, Chung Li-ho, and Zhong Zhaozheng in Issue 2 of the Wenyou Tongxun (Literary Friends Communications). Courtesy of the Chung Li-ho Culture and Education Foundation.

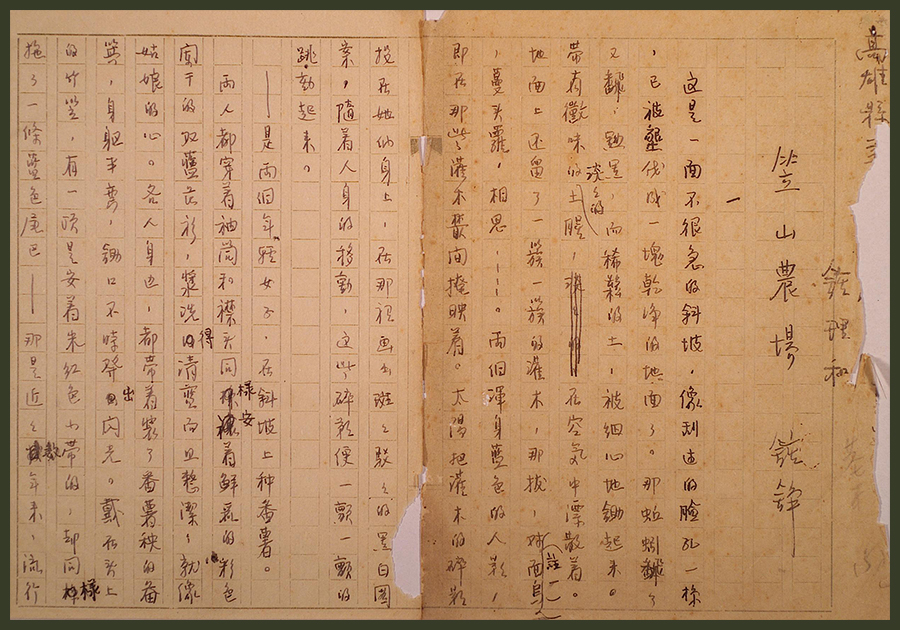

Caption: Manuscript of Chung Li-ho’s Lishan Farm. Courtesy of the Chung Li-ho Culture and Education Foundation.

Western literary thought started to make its way to Taiwan in the early 1950s. Ji Xi'an’s Xiandaishi (Modernist Poetry, 1953), the Lanxing Zhoukan (Blue Star Weekly), founded by Qin Zihao and Yu Guangzhong in 1954, and the Chuangshiji (Epoch Poetry Quarterly), founded by Luo Fu, Ji Xi'an, and Chang Mo in 1954, all translated and promoted creative writing methods and literary thought from the US and Europe. The Wenxue Zazhi (Literary Review) founded by Xia Ji'an in 1956 also played an important role in spreading Western literary theory and translations of Western works of different styles. Together with his brother Xia Zhiqing, Xia Ji'an established a new paradigm for literary criticism in Taiwan and laid the foundations for modernist literature in Taiwan, which would continue to develop in the 1960s.

Caption: Inaugural issue of the Wenxue Zazhi (Literary Review). Collection of the National Museum of Taiwan Literature.

Overall, the period from 1945 to 1960 saw a rupture between Taiwanese literature and the Taiwanese writers and works of the Japanese colonial era. Following this, the development of Taiwanese literature started to merge with that of modern Chinese literature. However, even though the dominant writers were Chinese who had fled to Taiwan from Communist China, this modern Chinese literature was itself different from the new literature tradition developing on the Chinese mainland because most works that were not right-wing were banned from publication in Taiwan.

Emerging writers learned from new Chinese literature and foreign literary works translated in China and Taiwan, and also from each other. In the early post-war period, the development of Taiwanese literature was characterized by a transition and new attempts to merge different styles, whether in terms of language, literary format, or subject matter. Taiwanese literature of this period shed the vestiges of classical Chinese and the unnatural Westernized vocabulary seen in new Chinese literature, and developed a simple and elegant vernacular Chinese writing style, while the literary format also replaced the complex repetition of traditional Chinese fiction. The roots of many features of the Taiwanese literature to come can be traced back to the 1950s.