Colonial Period: Japanese-language New Literature

BackColonial Period: Japanese-language New Literature

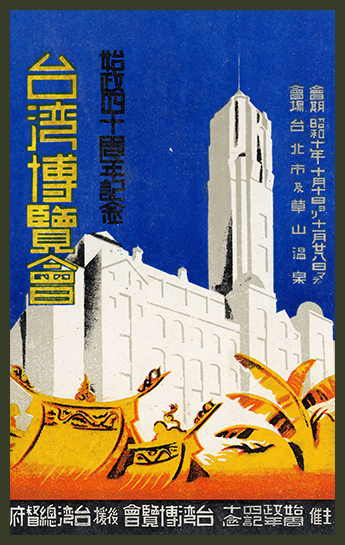

Caption: Postcard of the Taiwan Exhibition commemorating the 40th year of Japanese governance. Collection of the National Central Library.

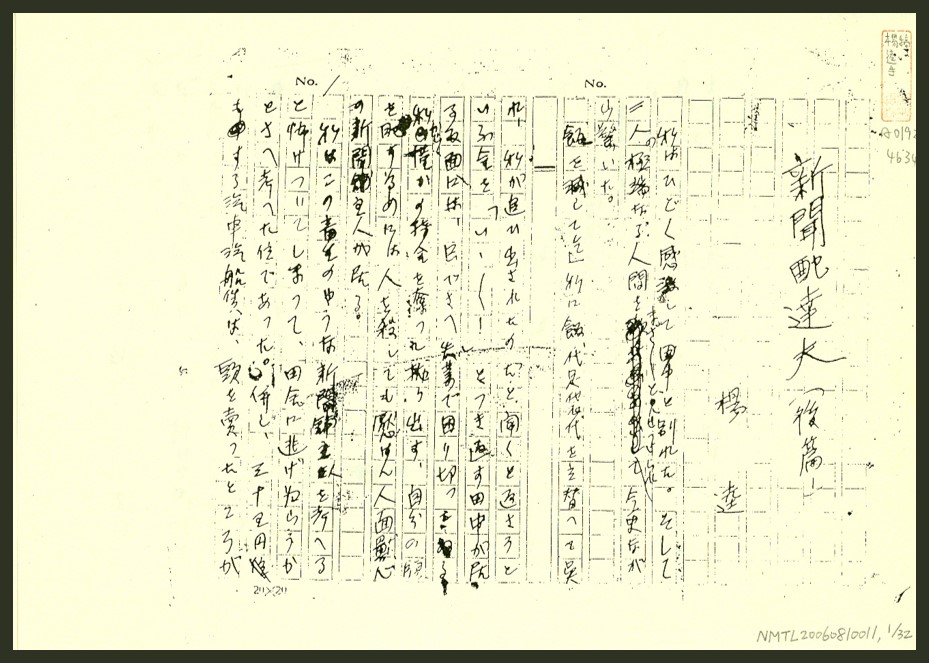

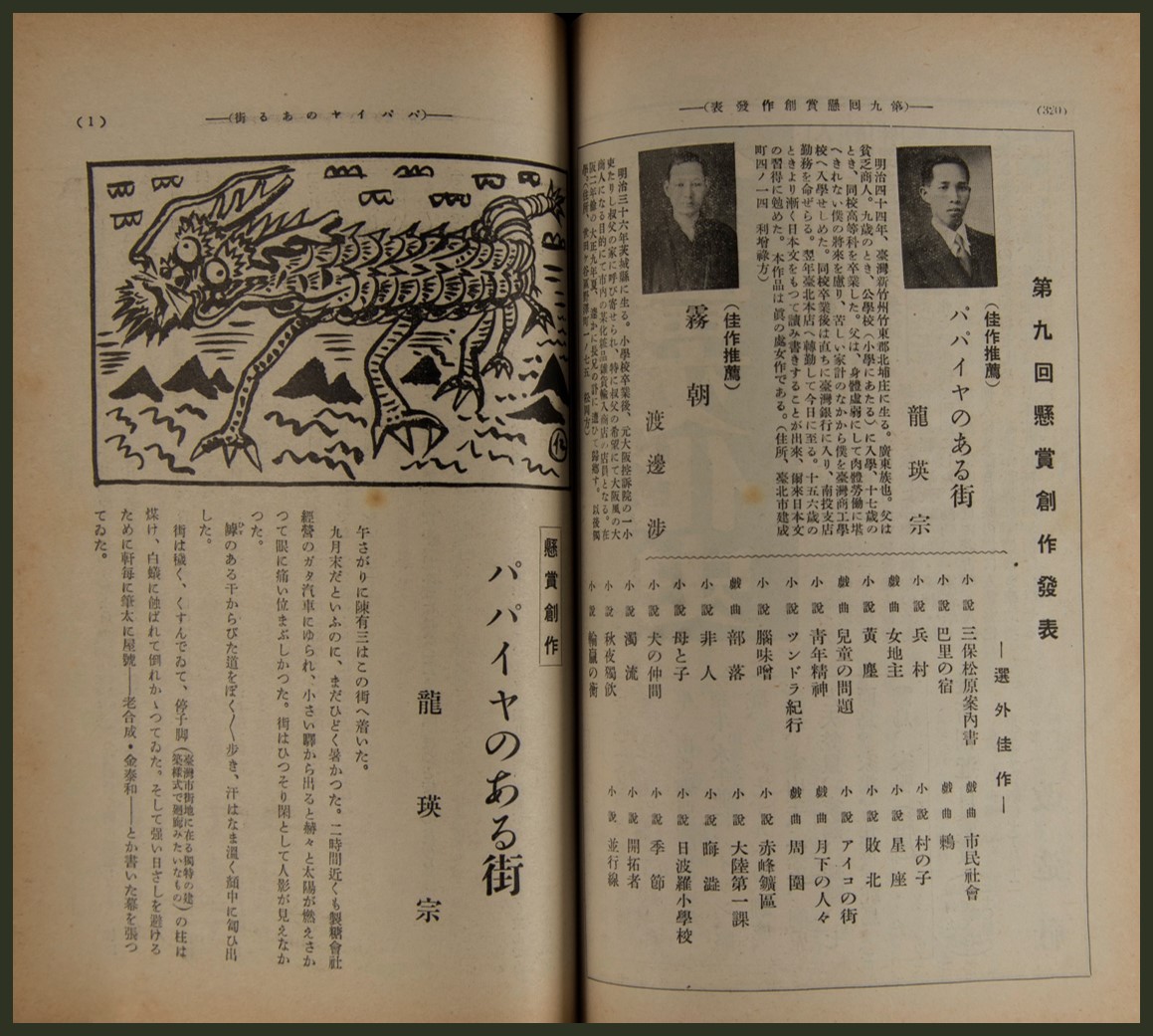

By the mid-1930s, the new literature in Taiwan had matured. In 1935, with much fanfare the Governor-General’s Office organized a Taiwan Exhibition to mark the 40th year of Japanese rule. At the same time, all manner of literary works were being created thanks to the mobilization and efforts of the island-wide Taiwan Literature and Art Union. What sets this period apart from the preceding one is that, instead of Chinese, Japanese became the language of expression, and many Taiwanese writers made their names in literary circles. For example, Yang Kui’s Shinbun haitatsufu (Newspaper Man) and Long Yingzong’s Papaya no aru machi (The Village with a Papaya Tree) both won important awards in Japan, propelling them to prominence in Taiwanese literature.

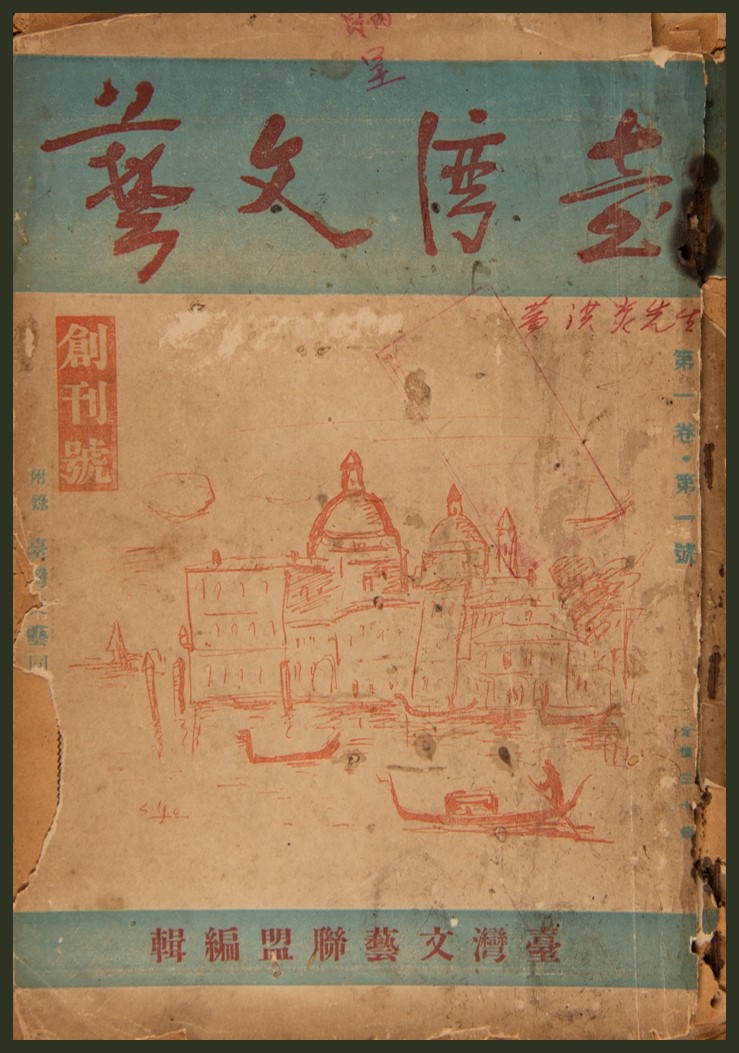

Caption: Inaugural issue of Taiwan Bungei (Taiwan Literature). Collection of the National Museum of Taiwan Literature.

Caption: Manuscript of Yang Kui’s Shinbun haitatsufu (Newspaper Man). Collection of the National Museum of Taiwan Literature.

Caption: Long Yingzong won the Kaizo magazine award with his Papaya no aru machi (The Village with a Papaya Tree). Collection of the National Museum of Taiwan Literature.

The last decade of Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan saw the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War. Against this backdrop and in accordance with the National Mobilization Law, the Governor-General’s Office shifted its policy on Taiwan and starting in 1939 promulgated a series of measures including the kominka (Japanization) movement, industrialization, and the southern expansion policy. On the cultural front, the pro-government Taiwan Literary Writers Association and the Taiwan Bungaku Houkoukai (Taiwanese Literature Public Service Association) were set up to help formulate and implement the colonial government’s arts policy. The Greater East Asia Writers’ Conference was held in 1942 and 1943 to promote support for the Japanese Empire and the ongoing war. However, while these government interventions may have restricted writers’ movements, they were not able to fundamentally shift the direction of development of Taiwanese literature.

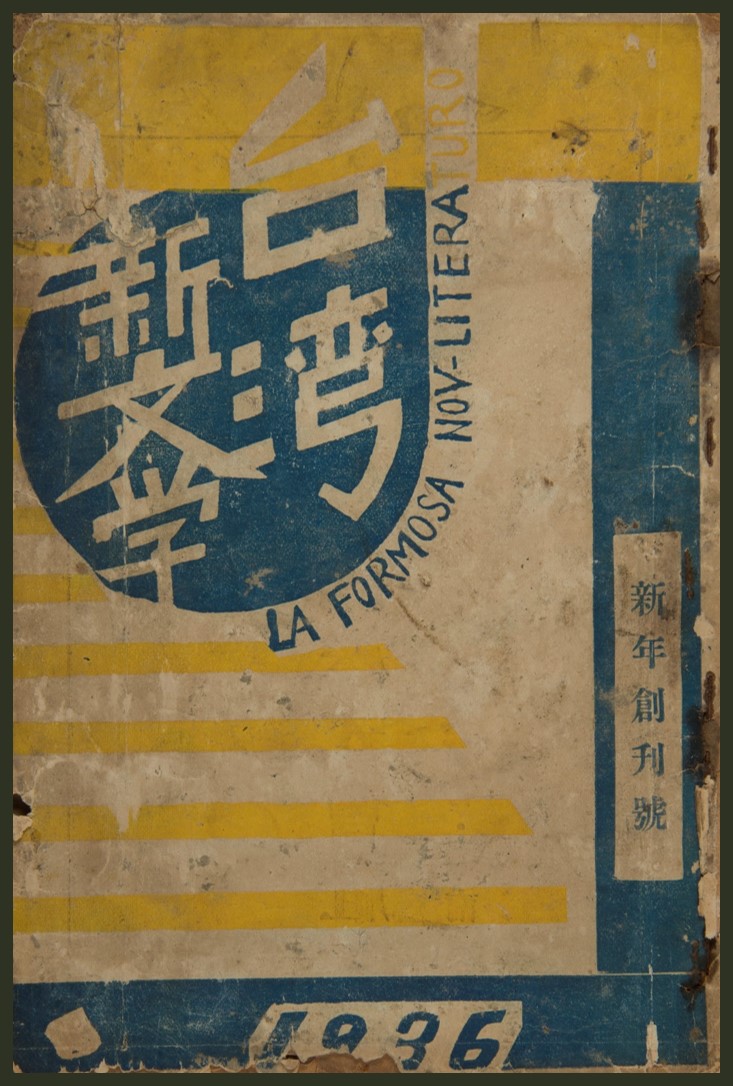

What is notable during this period is a change in the direction of literary thought. In continuation of the new literature movement’s focus on the socially disadvantaged and its critique of injustice, when the island-wide Taiwan Literature and Art Union was founded in 1934, its stated objective was to create a popular literature and make literature accessible to the public. Many of the union’s ideas were publicized in the form of literary comments and reviews in its official publication, Taiwan bungei (Taiwan Literature), or in the form of seminars around 1935. The most distinguished of these writings were Liu Jie’s and Yang Kui’s introduction to socialist literary theory. After 1936, under Yang Kui’s direction, Taiwan shinbungaku (Taiwan New Literature) solicited the involvement of both Taiwanese and Japanese writers in Taiwan and left-wing writers and scholars contributing to Japan’s Bunga kuannai (Literary News) and Bungaku hyouron (Literary Commentaries) in order to discuss the creation of a colonial literature. Yang’s journal bolstered literary exchange between Taiwan and Japan and the awareness of a united front of international popular literature, thus bringing Taiwanese literature to a new level.

Caption: The inaugural issue of Taiwan shinbungaku (LA FORMOSA NOV-LITERA). Collection of the National Museum of Taiwan Literature.

Around the same time, a literary school in the vein of Western liberalism was also on the rise, its main advocates being Japanese writers and scholars in Taiwan. Some of these writers wrote from a humanistic point of view on their observations of the development of new arts in Taiwan. One such writer was Nakayama Susumu, who from 1936 to 1937 wrote ten articles under the title “Seinen to Taiwan” (The Youth and Taiwan), covering such topics as the arts, theater, and literary movements. Some writers, including Takemura Takeshi and Shibutani Seiichi, focused on creating a literary language, style, and artistic techniques, and portraying the author’s mental process. Others followed the literary activity of Japanese writers in Taiwan and produced academic research and literary criticism on the history of Taiwanese literature from the point of view of the colonizer. Shimada Kinji, lecturer at the Taihoku Imperial University, was representative of this group and put forward the term gaichi burigaku (“theory of colonial literature”) to position the writings of the Japanese in Taiwan. In his contributions to the journal Kareitou (Splendid Island), Shimada hailed the embellished writings of Satō Haruo and Nishikawa Mitsuru on Taiwan, which were full of imperialist nostalgia and exoticism, as benchmark works for understanding Taiwan. Shimada’s literary discourse contrasted strikingly with those of Taiwanese writers around 1940 such as Huang Deshi. Huang’s “Taiwan Wenxueshi Xushuo” (Introduction to the History of Taiwanese Literature) traced the development of Taiwanese literature that started from a Chinese cultural tradition and reflected a Taiwanese identity.

Caption: Hamada Hayao, Long Yingzong, Nishikawa Mitsuru, and Zhang Wenhuan. Courtesy of the Long Yingzong Literature Foundation.

These two literary schools eventually clashed, leading to the so-called kuso riarizumu (“feces realism”) debate. On one side were aestheticist Japanese writers represented by Nishikawa Mitsuru, who criticized the realist writers headed by Yang Kui for only writing about the vulgar parts of life. However, all debates on literary theory came to an end as war intensified and literature was subjugated to patriotic fervor.

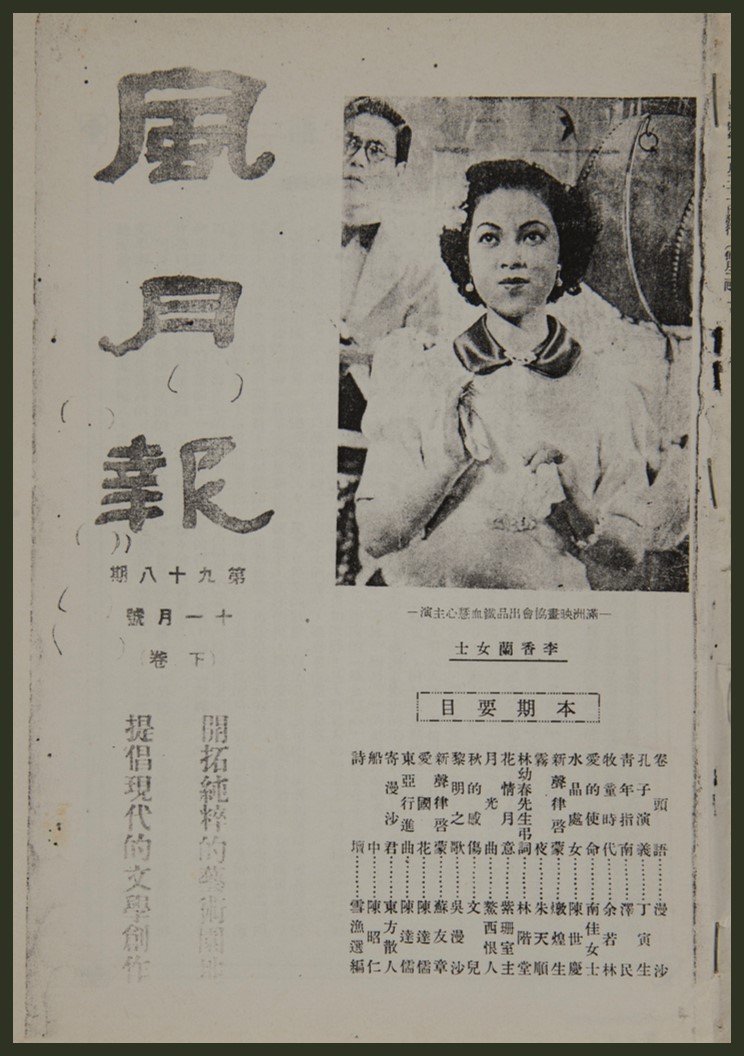

Reflecting changes in literary theory, literature itself also underwent a deep transformation in terms of both form and content. One important development was the emergence of new genres. Owing to an increase in the Japanese population in Taiwan and the Governor-General’s Office policy of attracting Japanese immigrants, there started to appear novels depicting cultural curiosity and intermarriage between Taiwanese and Japanese (e.g. Shōji Sōichi’s Chin fujin [Madame Chen]) or that took as their subject Japanese emigration to Taiwan (e.g. Hamada Hayao’s Nanpou iminmura [A Settlers’ Village in the South]). On the other hand, Taiwanese readers who did not read Japanese could find entertaining literary works written in Chinese, which became more available with urbanization and the rise in consumer culture in Taiwan. In addition to the traditional genres of legal fiction and marvelous tales, the modern genre of romance also hit the market. The main publication to carry romance stories, Fengyue Bao (Wind & Moon Journal), was the only Chinese-language journal that remained after the Governor-General’s Office abolished Chinese-language columns in newspapers and journals in 1937.

Caption: Fengyue Bao (Wind & Moon Journal), Issue 98. Collection of the National Museum of Taiwan Literature.

In response to the emergence of new genres, literary fiction also saw changes in the form of new artistic techniques and character types. Thus, Zhang Wenhuan’s Geidan no ie (A Geisha’s House, 1941) is a representative novel of manners. Another notable development was the changing image of intellectuals, who had long occupied an important place in new literature. One of the intellectuals educated in the colonial school system and who grew up during the modernization of the colony was Yang Kui. In Shinbun haitatsufu (Newspaper Man, serialized from 1932 to 1934), Yang wrote about a young man full of fervor for the ideals of an internationalist revolution coming face to face with the reality. In Moluo (Decline), Wang Shilang portrayed the vicissitudes of a character who became despondent after being jailed for participating in left-wing political activities, and many of Long Yingzong’s works are populated by depressed urban intellectuals.

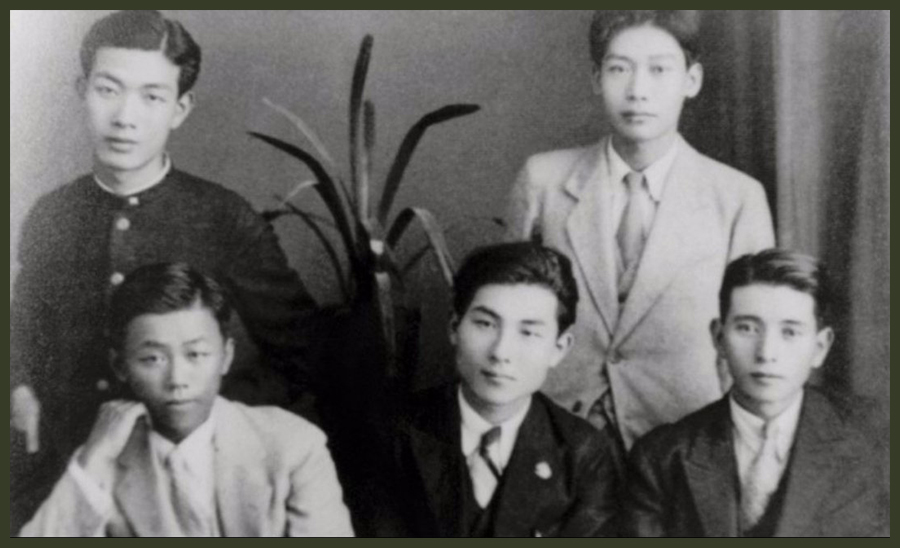

Alongside these naturalist novels full of doom and gloom are fictional works depicting nihilists in the form of journals and monologues, such as Guo Shuitan’s “Aruotoko no shuki” (A Man’s Diary, 1935) and Weng Nao’s “Zansetsu” (Remnant Snow) and “Yoakemae no koi monogatari” (Love Story Before Dawn). These works, with their fin-de-siècle sensibility, were, together with the experimental surrealist poems of the Fengche Poetry Society, the earliest modernist literary works in Taiwan in the 20th century.

Caption: Members of the Fengche Poetry Society. Courtesy of Yang Qifen.

These works, described at the time by literary commentator Huang Deshi as depicting intellectuals escaping reality, constituted the most beautiful literary landscape in the last decade of Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan. In contrast to authors who, whether willingly or not, sang the praises of colonial rule and the war (after the Pacific War broke out in 1941), these modernist authors working in a colonial context never lost sight of the value of literature, and their works are indeed important treasures of 20th century Taiwanese literature.