Leader Lin asked questions to a young woman whose name was unknown. The way he spoke seemed so awkward, almost childlike. Yet, however clumsy he was, the language touched the other person’s heart subtly. Surprised, the woman felt speechless. Language was such a magical and unbelievable means. It encouraged the woman shrouded in sorrow to speak. And this made the lonely soldier deeply excited.

——Chen Chien-wu, Hunting Captive Women

▒ Chen Chien-wu ▒

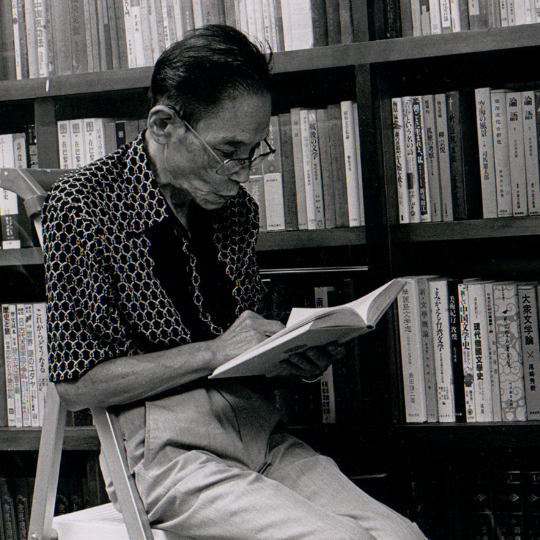

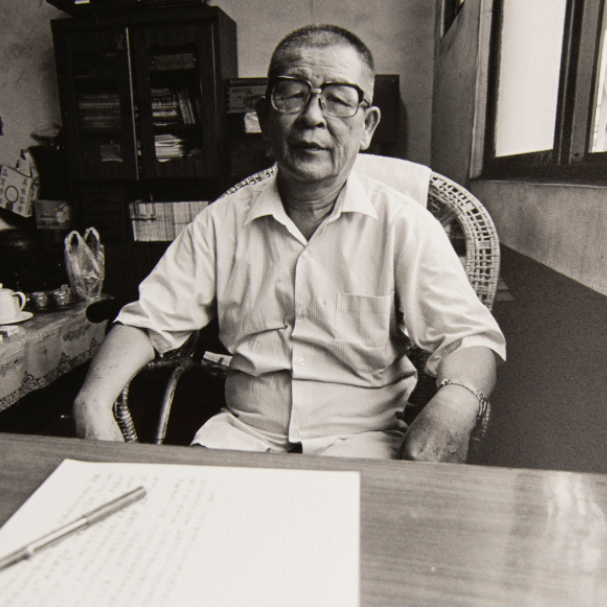

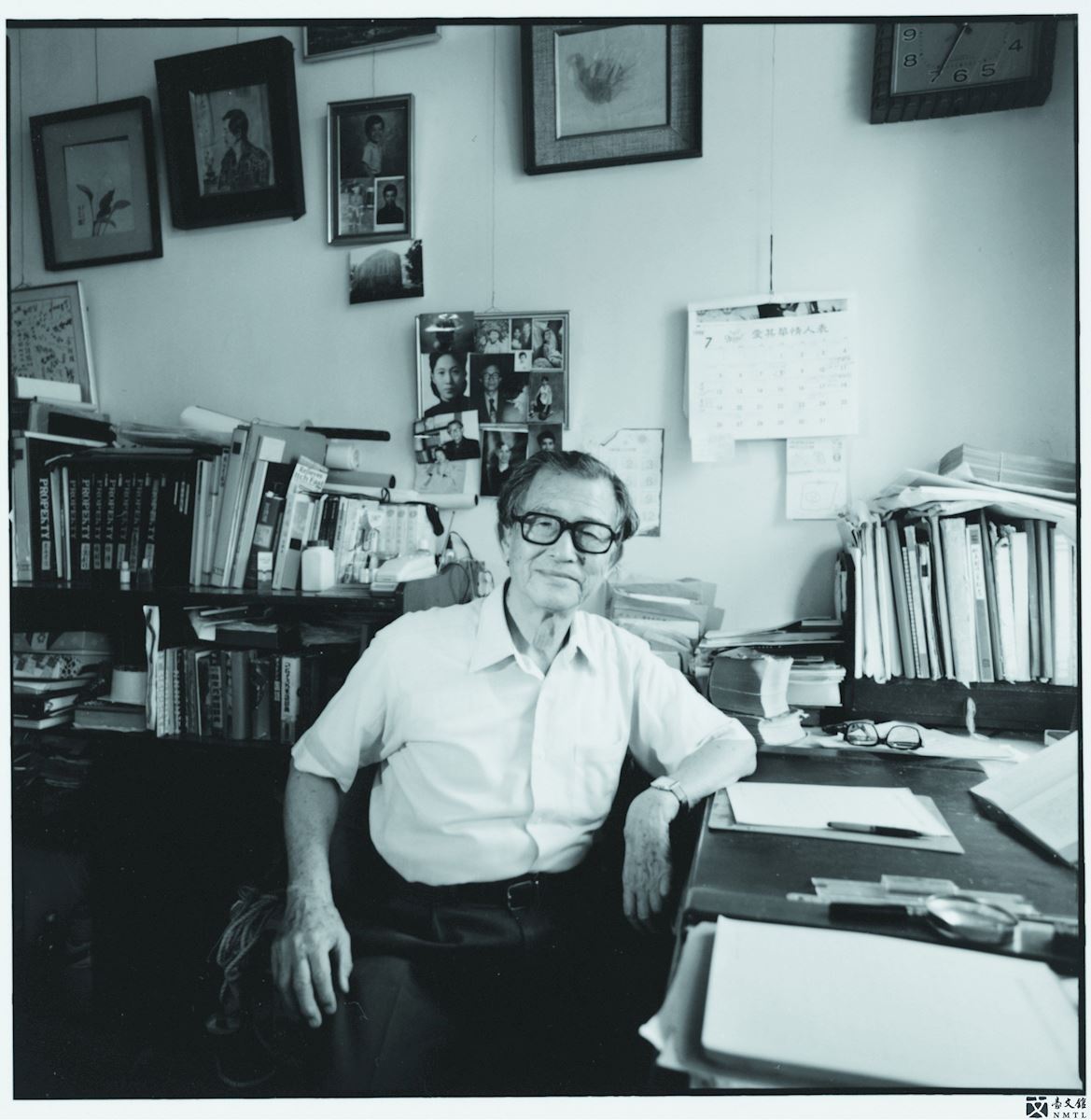

Chen sat beside a writing desk at his place, with one elbow on the desk. Sanmin Road, Taichung, July 1998.(Provided by Lin Po-Liang)

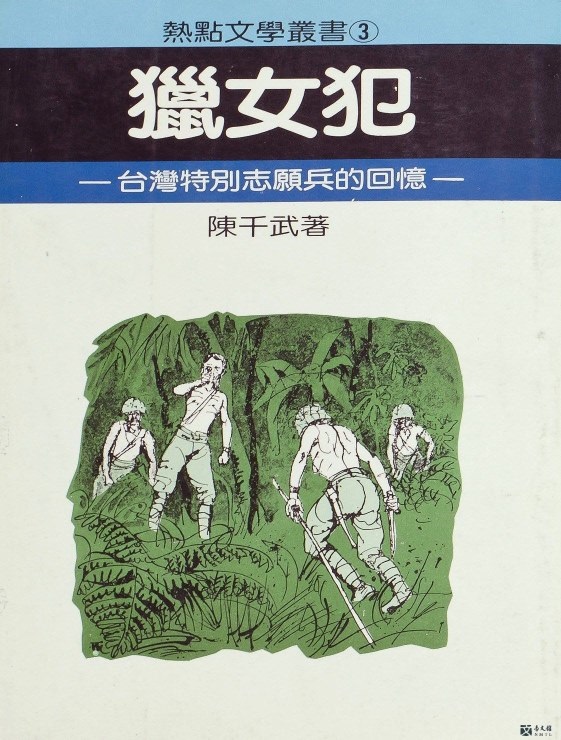

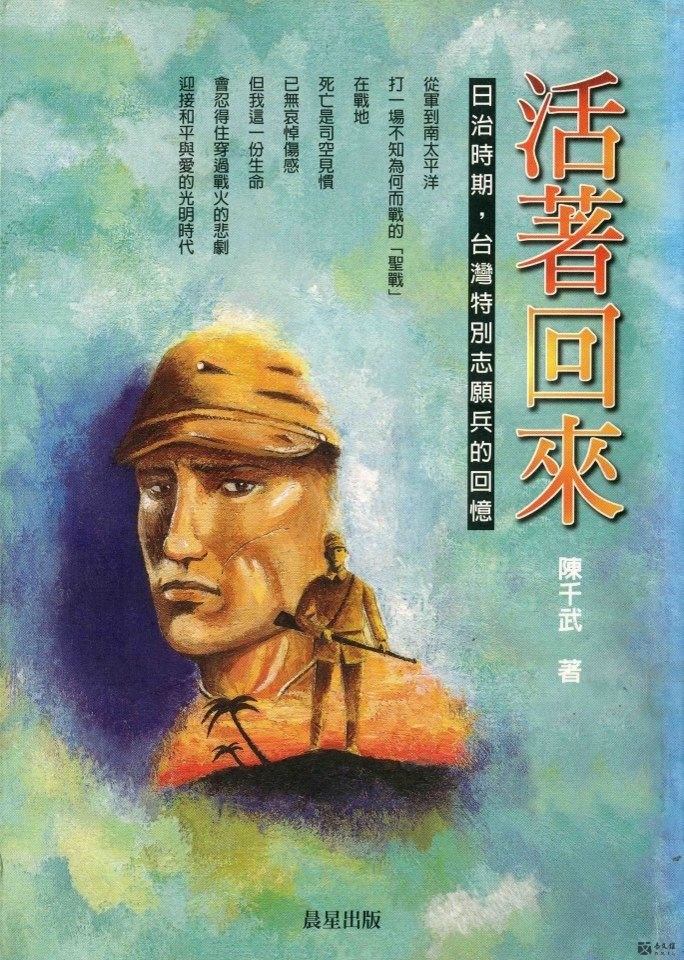

📖 “Hunting Captive Women” & “The Complete Works of Chen Chien-wu” & “Return Alive by Chen Chien-Wu”

Introduction

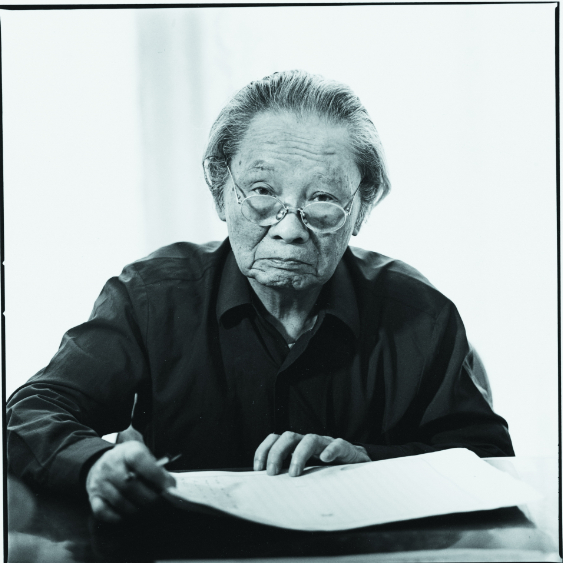

Chen Chien-wu (1922-2012) was born in Nantou and he used “Huanfu” as his pen name. Since releasing his first poem in 1939, Chen had devoted to writing poems, novels and reviews, as well as doing translation and assisting poets from Taiwan, Japan and Korea in exchanging ideas. He contributed much effort to promoting children’s poetry, too. Going out of his way to develop Taiwan’s culture, Chen as a poet was surely passionate about life.

An outstanding figure on this island, Chen established Li Poetry, a magazine, and Poetry Outlook, a printed journal. He was the president of Taiwan Writing Society and Taiwan Provincial Children’s Literature Association, and a consultant for Taiwan Modern Poets Association. He not only wrote poems but also promoted poetry. Looking at Chen Chien-wu’s nearly-70-year literary career, one realizes his experiences in the Pacific War could not have been possibly acquired by most Taiwanese writers. Thus, his poems and novels about the Pacific War became important Taiwanese literary assets.

With devotion and careful writing plans, Chen successfully depicted people’s struggles during the war, facing life, death, love and lust. He daringly revealed the rawest sides of humanity, our survival instinct, and the nobility of the Taiwanese as a minority group who support one another in a wild modern jungle.

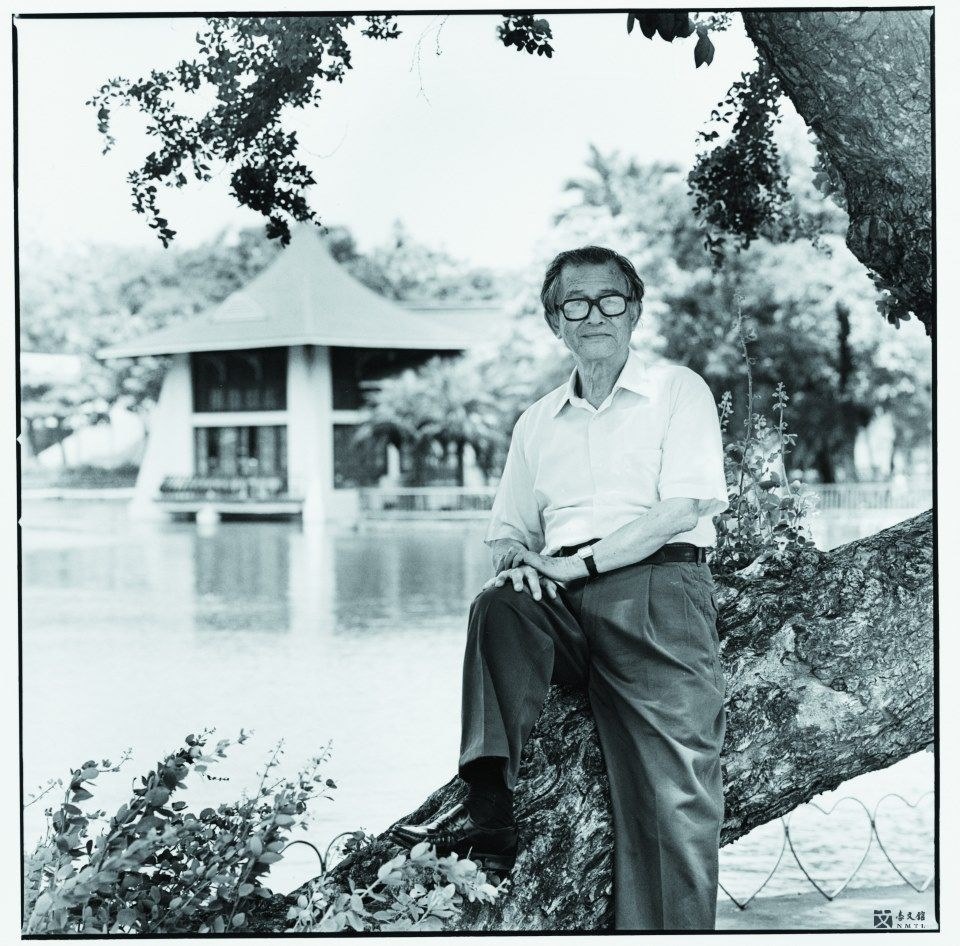

Chen Chien-wu

Chen Chien-wu sitting on a tree trunk, Taichung Park, July 1998.(Provided by Lin Po-Liang)

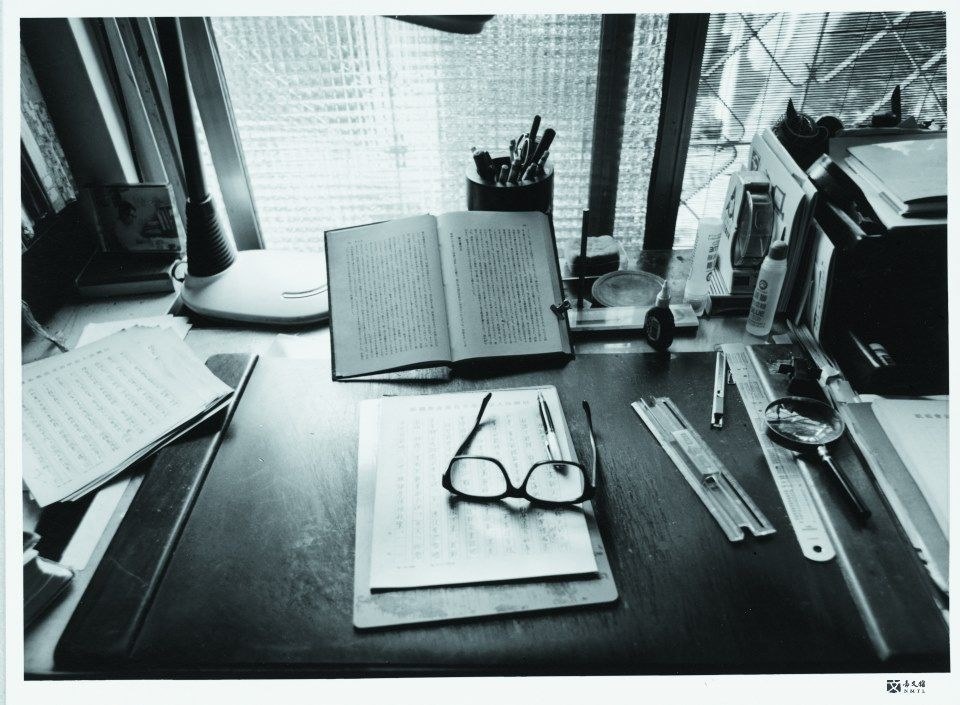

Close-up of Chen Chien-wu’s writing desk.

Close up of Chen Chien-wu’s desk, Sanmin Road, Taichung, July 1998.(Provided by Lin Po-Liang)

|

|

🎬 “Give the mosquitoes a name for honor” by Chen Chien-wu

Manuscript

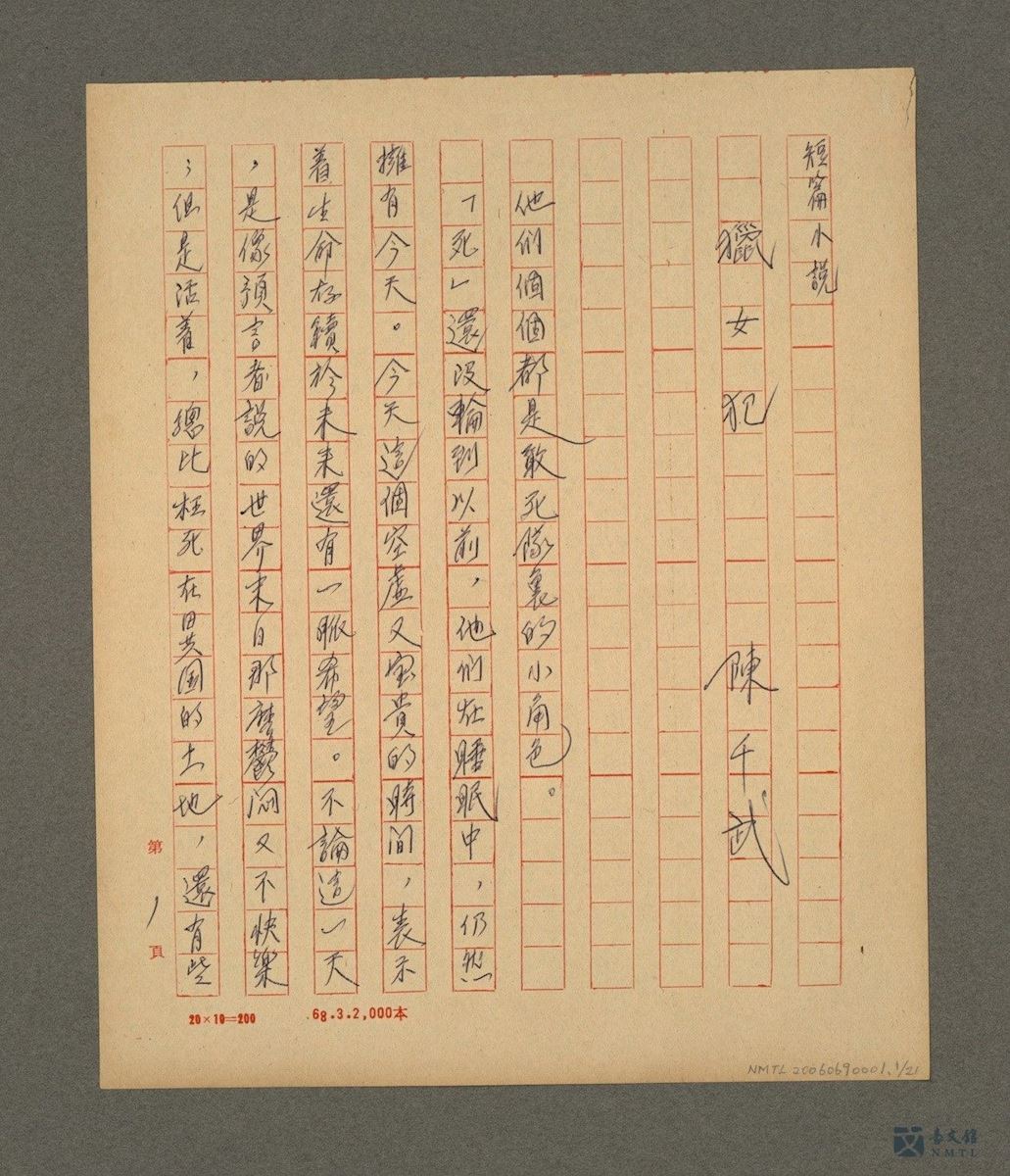

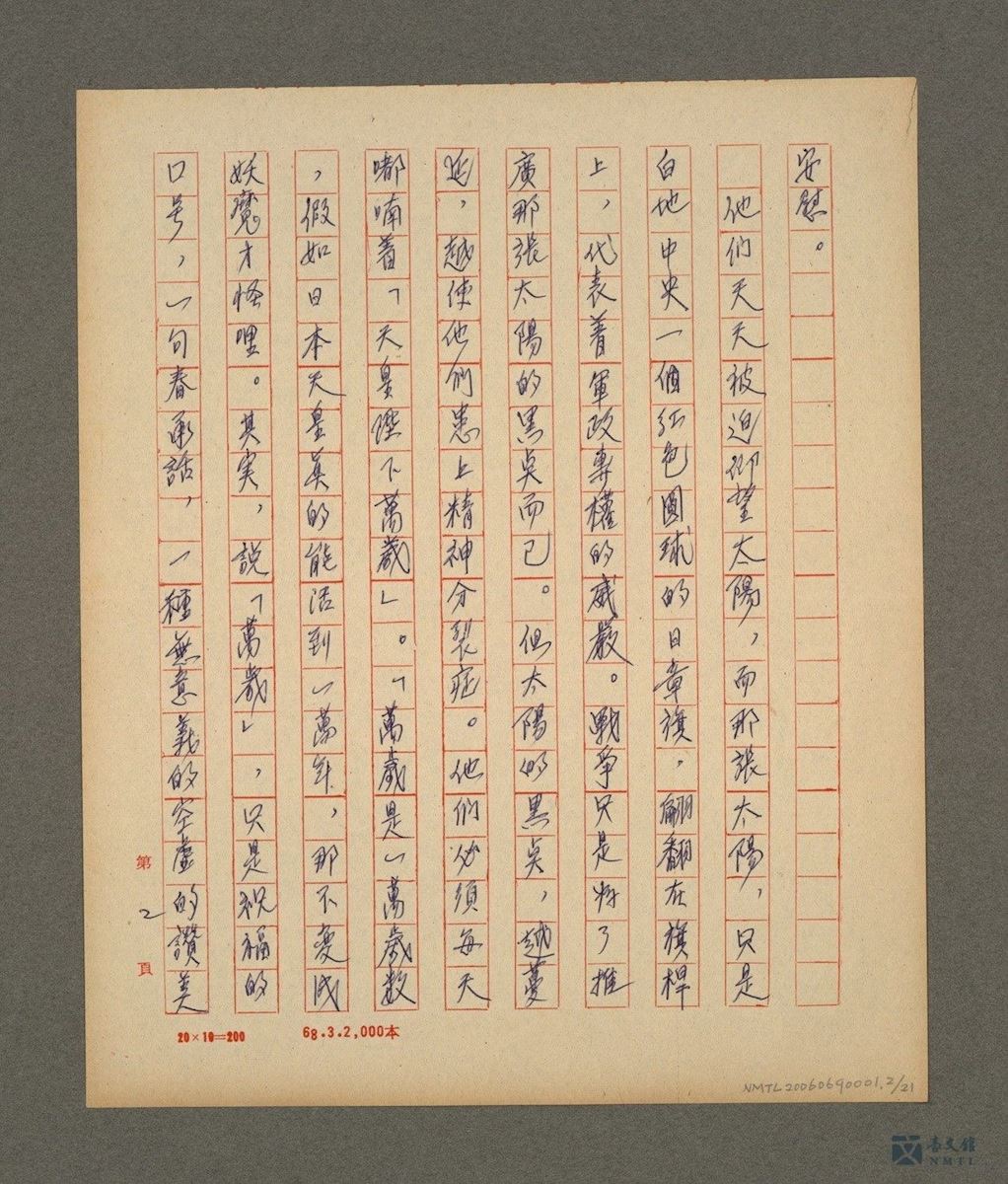

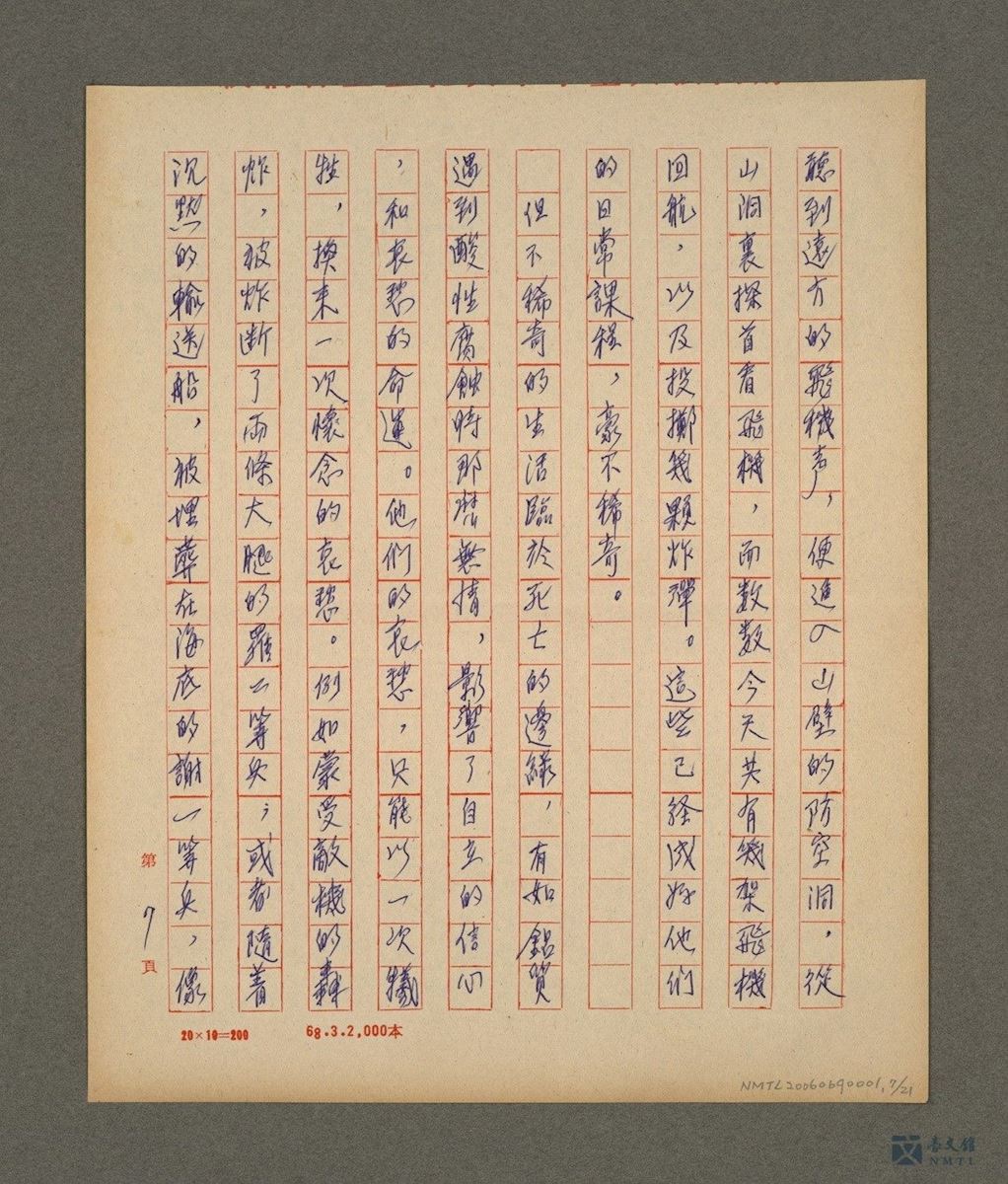

► “Hunting Captive Women”

The story is based in Timor which was previously occupied by the Netherlands and Portugal. During the war, it was taken over by the Japanese army. The voluntary soldiers from Taiwan also received the training for “suicide squads” there. The soldiers were encouraged to go to “comfort centers” where women were provided for sexual pleasure. Lai Sha-lin was a key character in “Hunting Captive Women.” A mixed-race woman, she was captured and sent to Timor to be a “comfort girl.” She saw all the Japanese soldiers who came into her working room for sexual comfort as “hunters,” and herself as a prey. When the protagonist came in just to see her and not “hunt” her, she was still scared. She would rather see him as a hunter.(Donated by Chen Chien-wu / Collected by National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

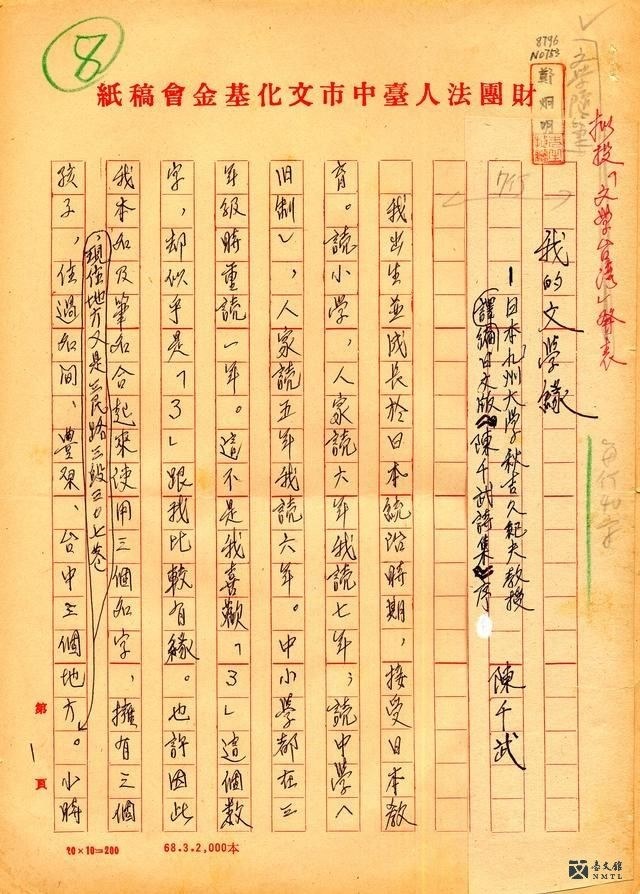

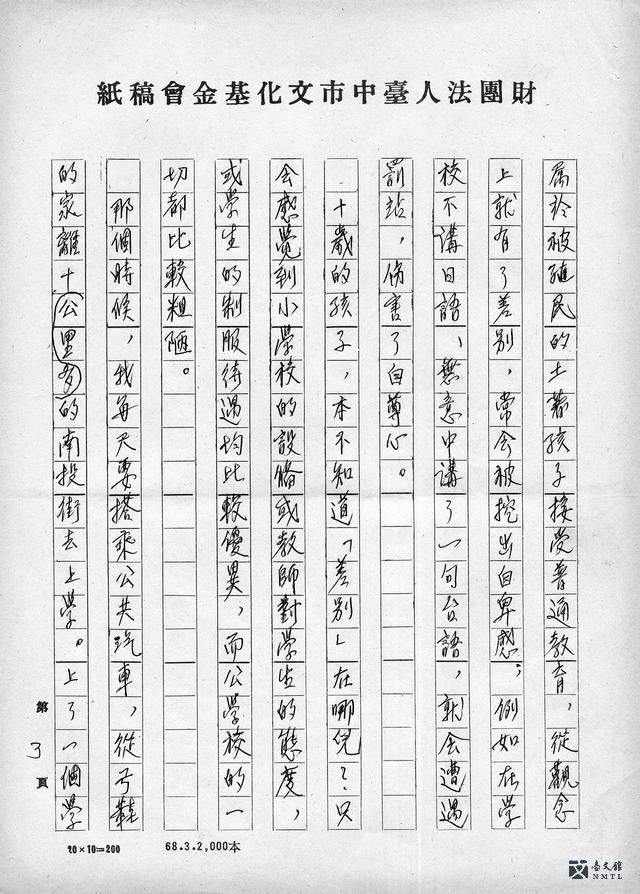

► “My Connections with Literature”– Preface to Poems by Chen Chien-wu, Japanese edition, edited and translated by Professor Akiyoshi Kukio of Kyushu University

In this article, Chen Chien-wu recalled how he got deeply involved in literature. The writer studied in both Japanese and Taiwanese elementary schools. This unique experience made him realize the differences and contradictions between the two. He realized that in each culture, a unique literary system exists. Thus, it is natural for Taiwanese poets to develop their own identity and awareness.(Donated by Literary Taiwan / Collected by National Museum of Taiwan Literature)