“Did you make the horse sculptures out of self-blaming?”

“At the time, Taiwanese people called the Japanese four-legged dogs, and the Taiwanese who worked for Japan three-legged dogs.”

“Why did you only make horses, not any other animals?”

“It’s because they only wanted horses. As I made the sculptures, suddenly, I seemed to see me in the horses. So I tried to put myself in them.”

I picked up each and every horse on the ground and in the corners. Every horse poses differently, but they have one thing in common: Their facial expressions and body gestures exude pain and guilt.

──Chen Ching-wen, Three-legged Horse

▒ Cheng Ching-wen ▒

Cheng Ching-wen, without a smile on his face but shadows at Photographers’ Studio, Linyi Street, Taipei City, November 2001.(Provided by Lin Po-Liang)

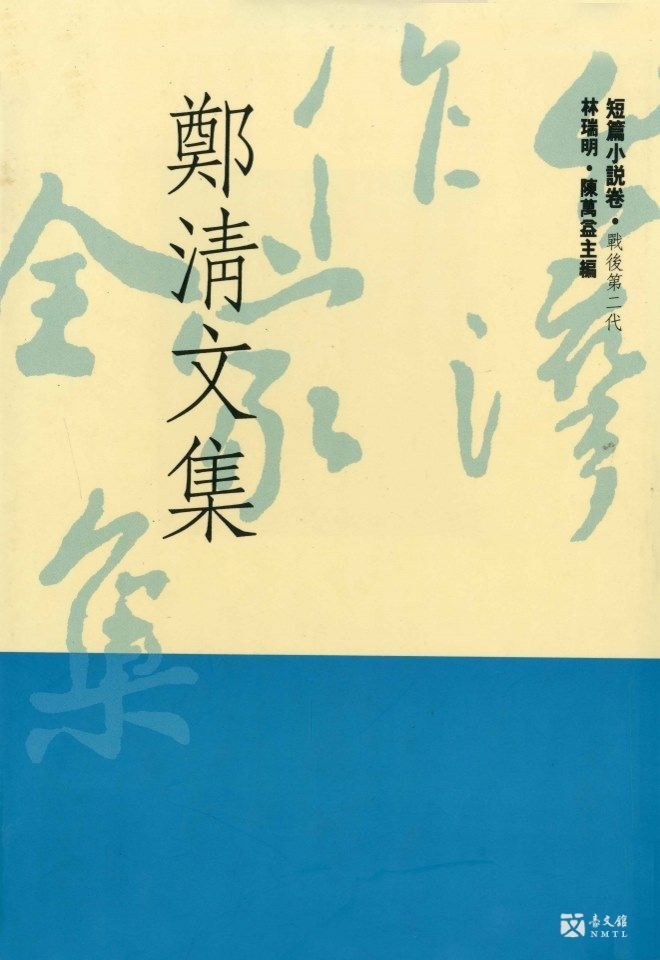

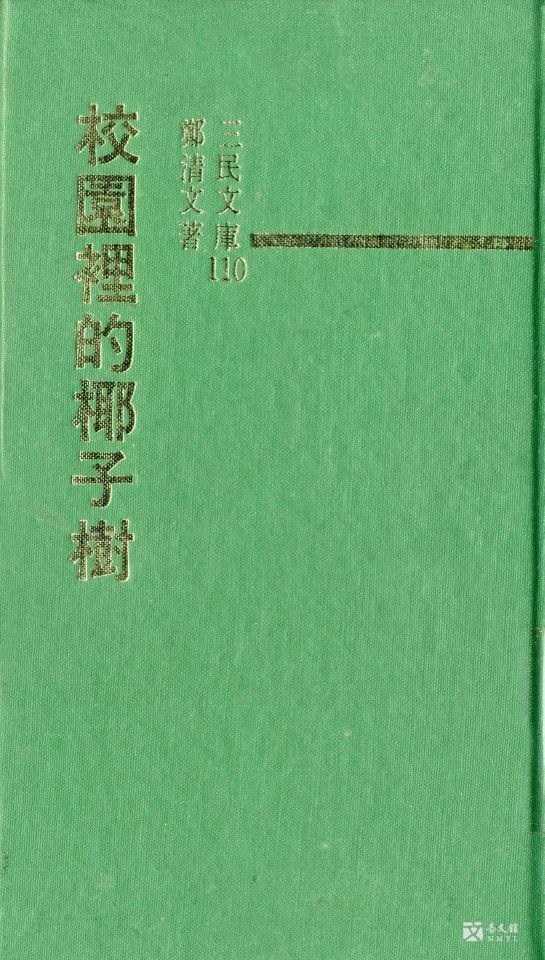

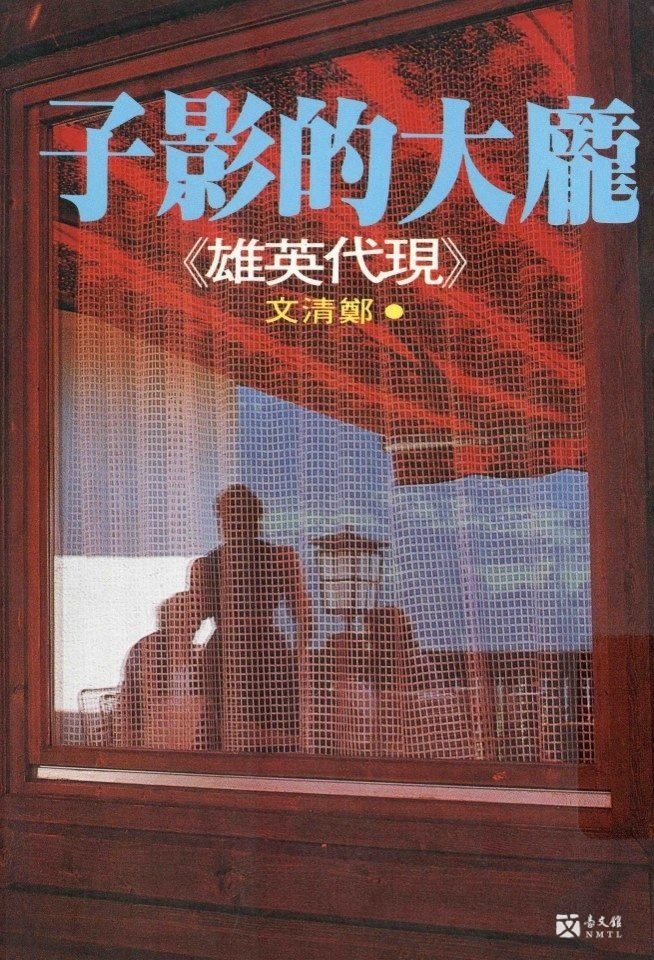

📖 “The Complete Works of Cheng Ching-wen” & “A Coconut Tree on Campus” & “Giant Shadows”

˙

Introduction

Born in Taoyuan, Cheng Ching-wen (1932-2017) held a few pennames such as Guba, Guluan and Chuangyuan throughout his life. In 1958, Cheng released his first novel entitled “A Lonely Heart” at the literary supplement of United Daily News, with renowned writer Lin Hai-yin as the editor-in-chief.

His other publications include Dustpan Valley, Giant Shadows, A Coconut Tree on Campus, Complete Short Novels of Cheng Ching-wen, and Sky Lantern & My Mother. His most representative short stories are "Suite on Water," "A Coconut Tree on Campus," "Giant Shadows," and "Three-legged Horse." In 1998, Three-legged Horse, translated into English, won the Kiriyama Pacific Rim Book Prize from the Pacific Rim Center based in the United States, as the first writer from Taiwan to receive the award.

When it comes to novels, Cheng insisted that “literature is life, it is art, and it reflects people’s minds.” He emphasized the realness of a novel’s content and the diversity and accuracy of its details. Exactly because he valued such qualities, Cheng was often able to truthfully depict the lives of Taiwan’s people across social classes through his fine stories, leaving precious records of humanity which have been slowly fading in Taiwan.

Cheng Chin-wen and his student.

Cheng Ching-wen and students in the Department of Taiwanese Literature, November 2001, Aletheia University.(Provided by Lin Po-Liang)

(1).jpg)

At the front of Cheng Ching-wen’s place.

The front of Chen Ching-wen’s place (calendar, flower pots, shoe racks), Cheng’s residence in Taipei, November 2001.(Provided by Lin Po-Liang)

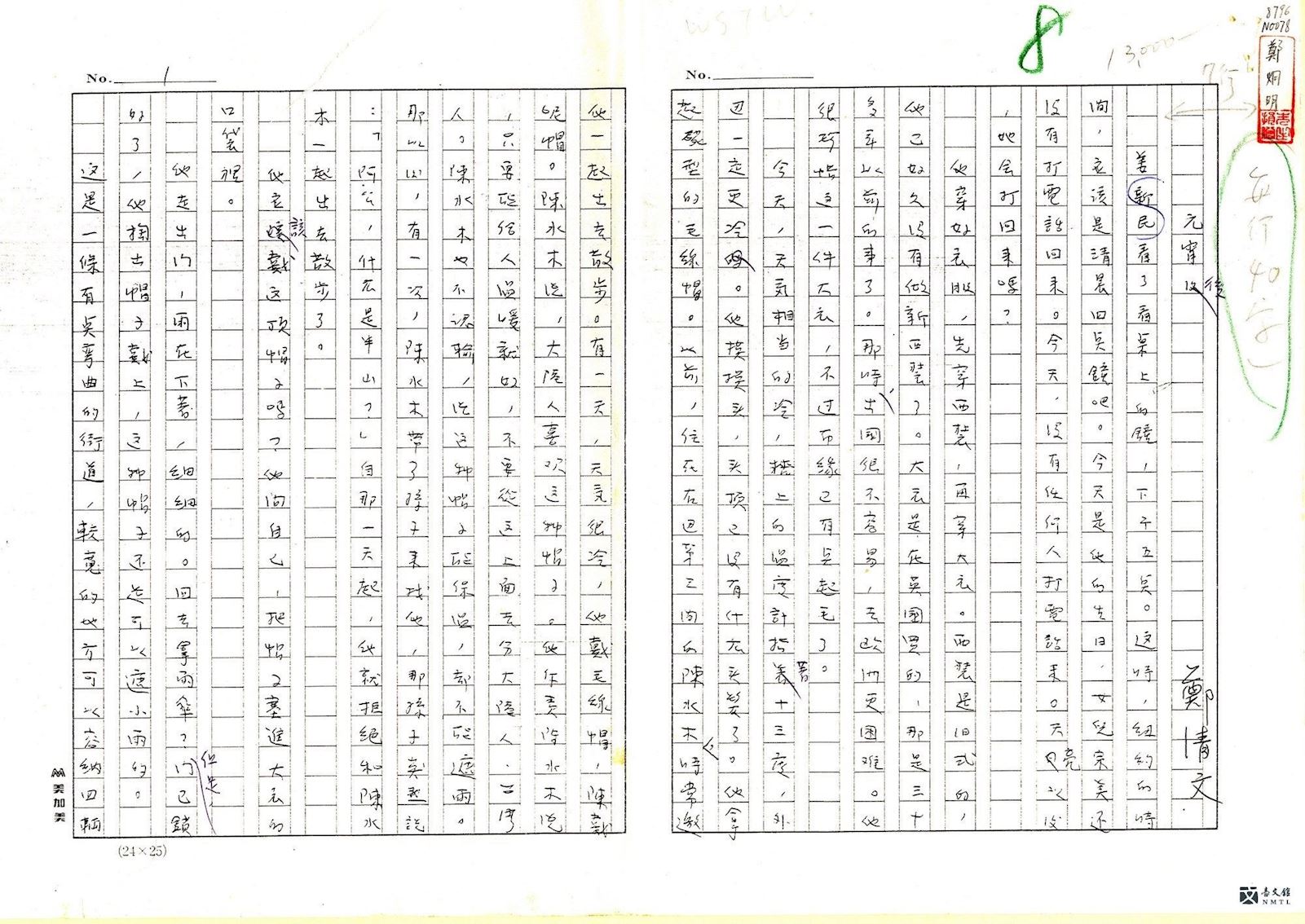

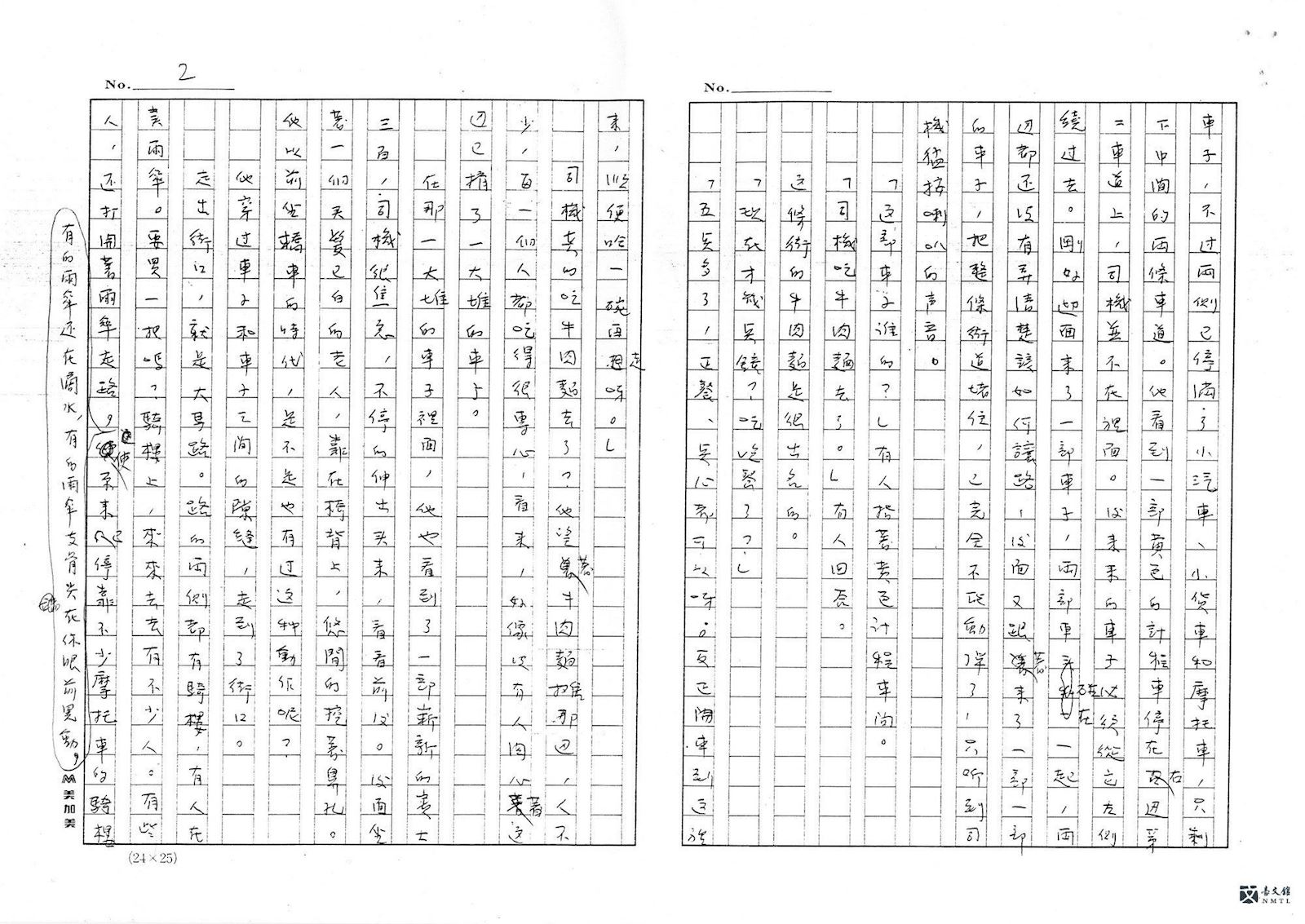

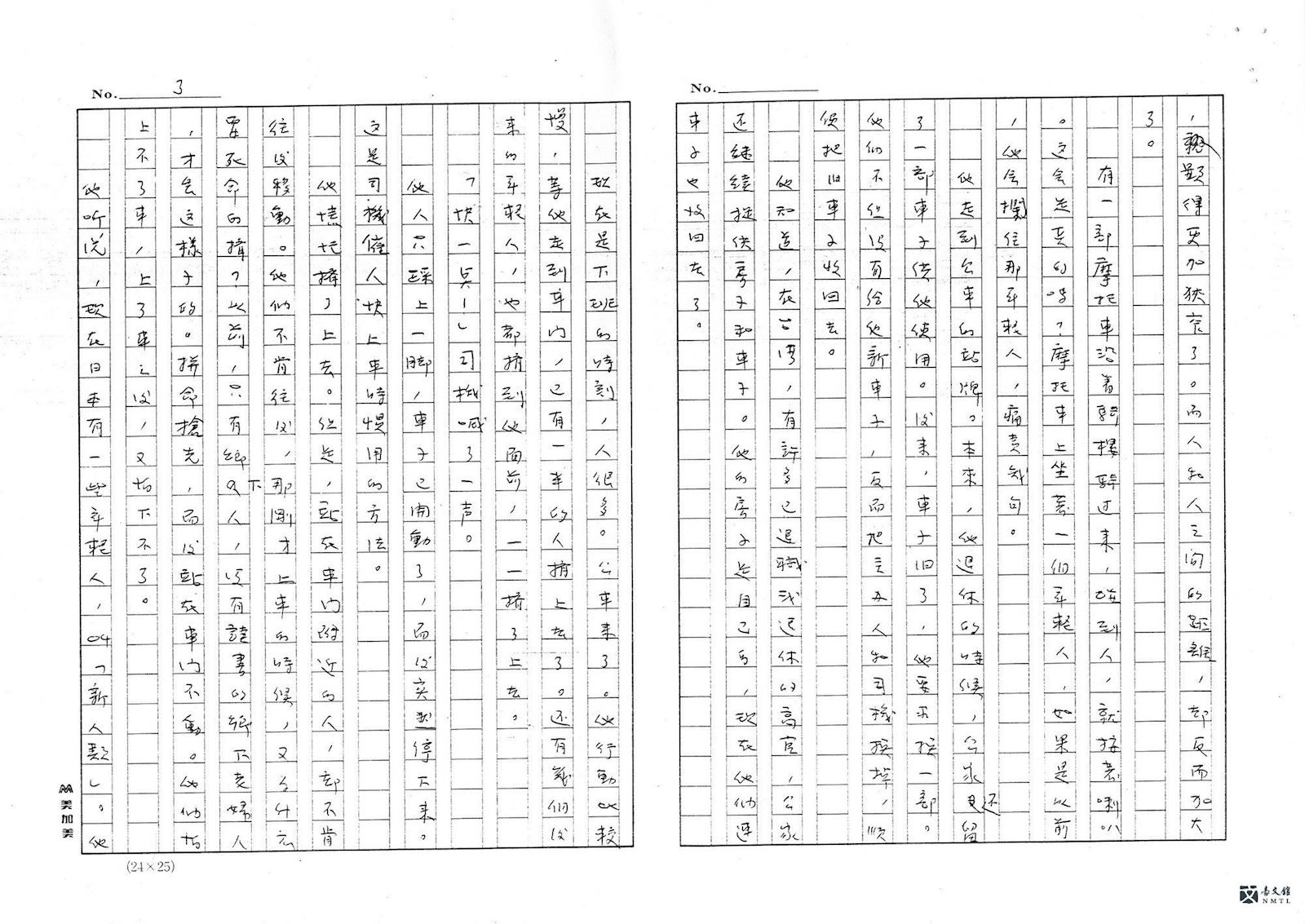

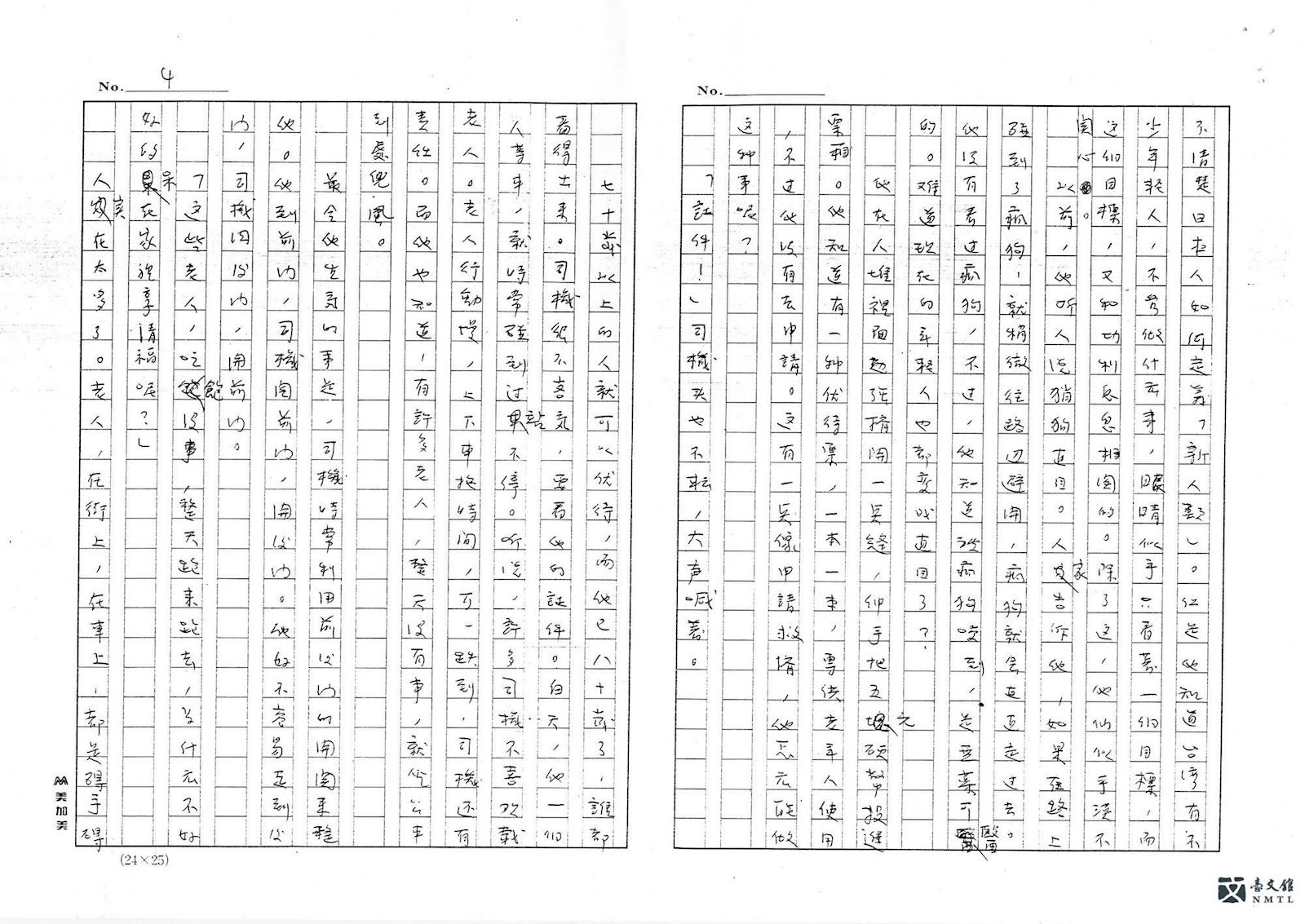

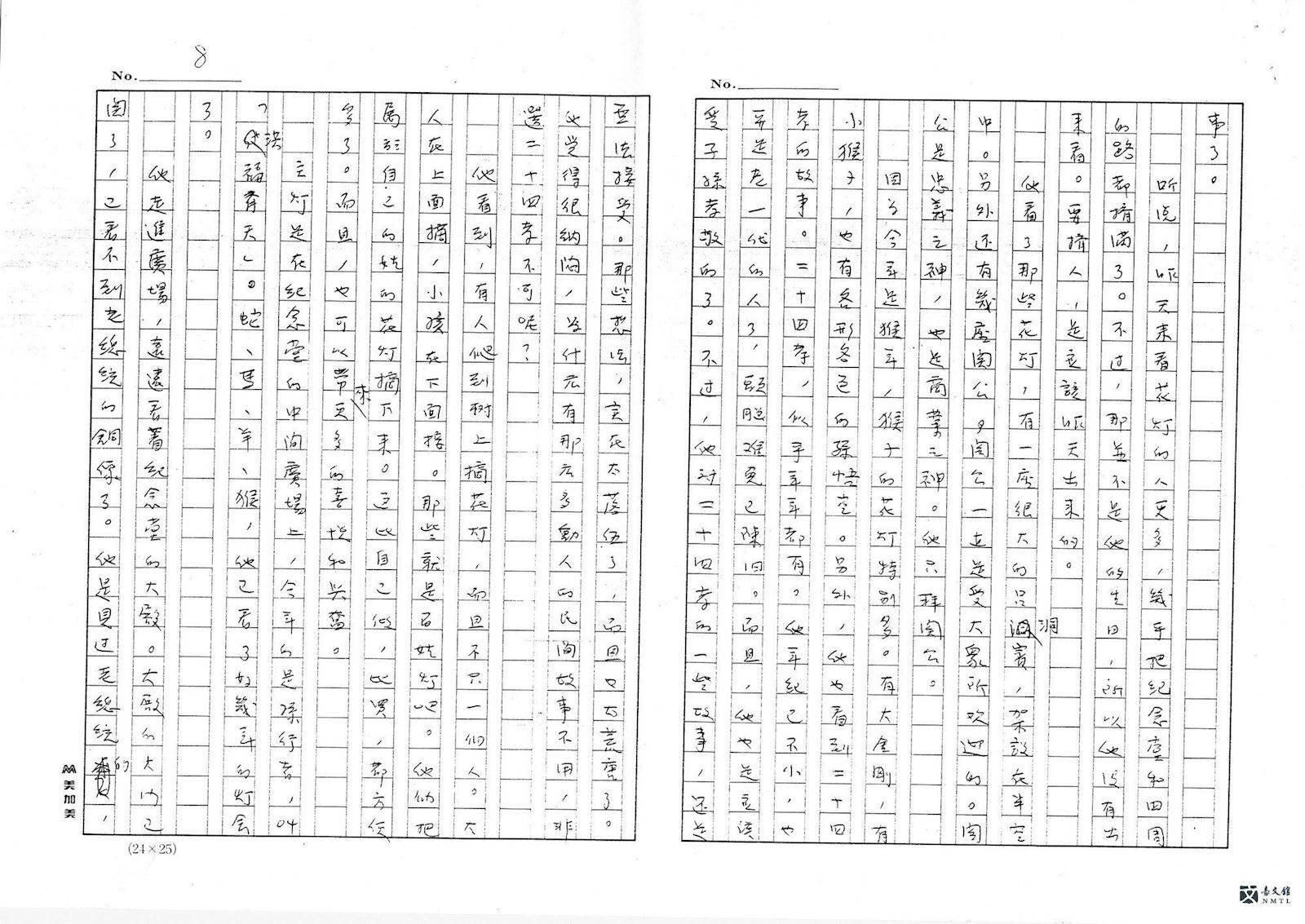

Manuscript

► “After the Lantern Festival” (copy)

This article tells the story of Chiang Min-hsin whose birthday fell one day after the lantern festival. Chiang took a bus at five in the afternoon to a memorial hall. Afterwards, he went home and waited for a call from his daughter wishing him happy birthday at midnight. During this time, Chiang thought of his daughter who supported Taiwan’s independence in the United States, his son who was a failure, Lin Yung-he who saw him as the one who killed his father, and his friend Su Shang-wen. A triumphant veteran returning to Taiwan after visiting mainland China, Chiang reflected upon his awkward socio-political identity during the Formosa Incident and the White Terror.(Donated by Literary Taiwan / Collected by National Museum of Taiwan Literature)