Heat Wave under Cold War| Modernist Élan| Stories of Hong Kong Literature

1949 saw the end of the Chinese Civil War on the Asian mainland, with the People’s Republic formally declared in Beijing and the Republic of China government regrouping in exile on Taiwan. Hong Kong was one of the few places still open to both sides, and its free market for ideas and ideologies created a literary landscape saturated with a fractious plentitude of perspectives.

However, Hong Kong’s position on the frontlines of the global Cold War in opposition to the spread of communist totalitarianism invariably influenced the political sympathies of its contemporary writers, whose works certainly impacted public sentiment during this period. Nevertheless, Hong Kong’s relatively open society remained an advantage. New literary and artistic trends from around the world were absorbed, synthesized, and woven into works of literature that were eagerly consumed not only at home but also in Taiwan and across the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia. This was Hong Kong’s aesthetic ‘soft power’.

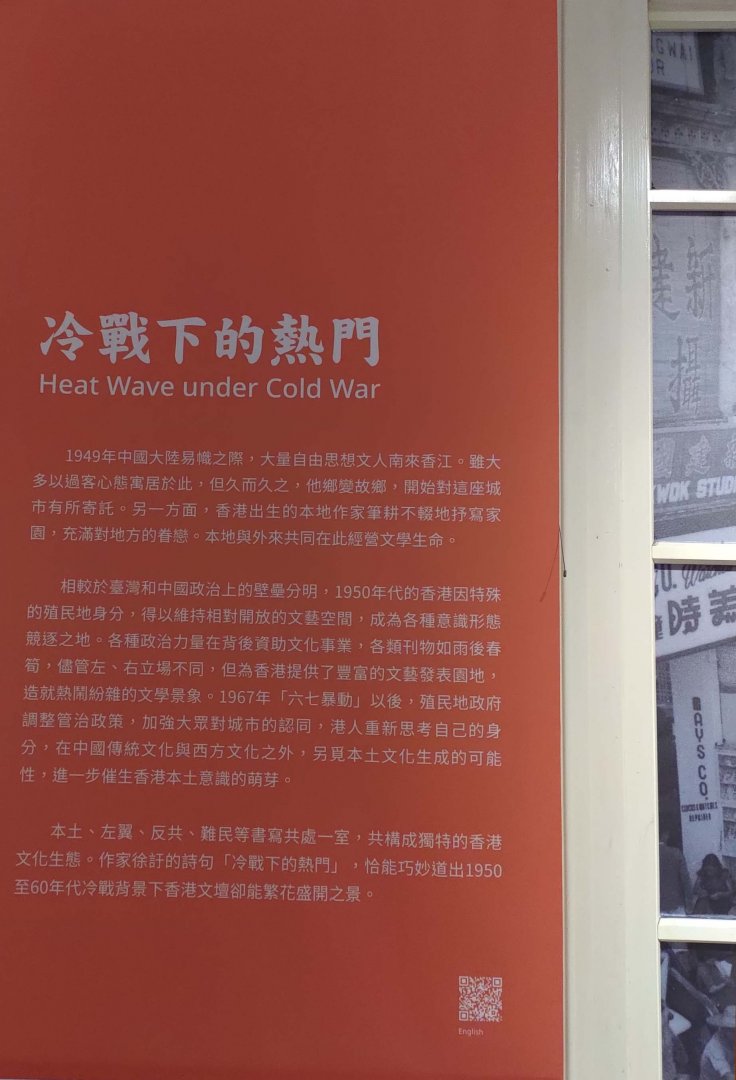

Heat Wave under Cold War

This is a generation of a strange combination of circumstances; this is a generation of making the best of a bad bargain.

── Chen Hui's Under the Sun (2016)

The regime change in China brought many liberal-minded Chinese intellectuals to Hong Kong in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Although initially viewing their stay in the colony as a temporary affair, many would ultimately come to embrace Hong Kong as home. Moreover, local writers during this period continued writing effusively about their native soil and experience. Both invested their talents to breathe new vitality into Hong Kong literature.

During the 1950s, Hong Kong's unique status as a British colony gave it a level of literary and artistic freedom and discourse that was impossible in either Taiwan or China at the time. Various political factions discreetly supported local cultural enterprises, with new journals and magazines proliferating like sprouts after a spring rain. Both left and right-leaning interests joined the fray, enriching Hong Kong's cultural landscape and generating a boisterous and diverse literary scene. A shift in colonial government policy in response to the 1967 leftist riots began encouraging citizens to rethink their relationship with their city in order to strengthen their self-identification with Hong Kong. This opened new possibilities for the emergence of a truly nativist culture and, subsequently, of a distinct Hong Kong identity.

Nativist, left-wing, anticommunist, and refugee literature all shared shelf-space in Hong Kong libraries and bookstores. Each were indispensable elements in Hong Kong's wholly unique cultural ecology. "Cold War chic", a poetic turn-of-phrase written by the émigré poet Hsu Yu (1908 – 1980), describes the flowering of Hong Kong's literary fortunes in the shadow of the Cold War in the 1950s and 1960s.

▲ Li Kuang “Yan Yu” / Hong Kong: Ren Ren Publication / 1952

▲ Hua Jia “On Dialect Literature and Art” / Hong Kong: Ren Jian Book House / 1949

.jpg)

▲ Tang Ren's Jin-Ling Chun Meng

▲ Yue Qian “Wen Jun’s Broken Dreams” / Taipei: Ming Xiong Publication / 1976

▲ Written by Wong Guk-Lau, translated by Masao Shimada, Keishu Saneto, “Shrimp Story” / Tokyo: San-ichi Publishing / 1950

▲ Gu Liu “Little Shrimp Part 1: Kinship Marriage” / Hong Kong: Xinmin Publication / 1948

.jpg)

▲ Eileen Chang's The Rice Sprout Song

.jpg)

▲ Shu Xiang Cheng “The Sun Has Set” / Hong Kong: Nanyang Publication / 1962

Modernist Élan

.jpg)

I'm dead, and that's it. What are those people talking and studying about? Are they talking and studying about the happiness of my emptiness?

── Kun Na's Door to the Land (1961)

The modernist journal New Trends in Literature and the Arts, launched by Ronald Mar (Ma Lang) in 1956, became the standard-bearer for modernist literature and thought in Hong Kong. Modernism engulfed the colony from the late 1950s through the 1960s, spawning a profusion of modernist poems, poetry criticisms, and novels that looked inward for meaning and purpose.

The mainstreaming of modernist ideas in Hong Kong in publications such as New Trends in Literature and the Arts, the 'Repulse Bay' literary supplement of the Hong Kong Times newspaper, and Modern Edition inspired and drew inspiration from several important contemporaneous modernist publications in Taiwan, including Modern Poetry and Epoch Poetry Quarterly. More than fertile soil for local writers, these publications were a platform for exchange and sharing between Hong Kong and Taiwan literary circles, with far-reaching influence on the development of modernist thought within both.

Despite differences in the underlying origins of modernist trends in the two areas, cross-fertilization of works, themes, and ideas ultimately led to modernism becoming a prominent and highly representative literary trend linking Hong Kong and Taiwan.

.jpg)

▲ The first issue of Literary Current Monthly Magazine

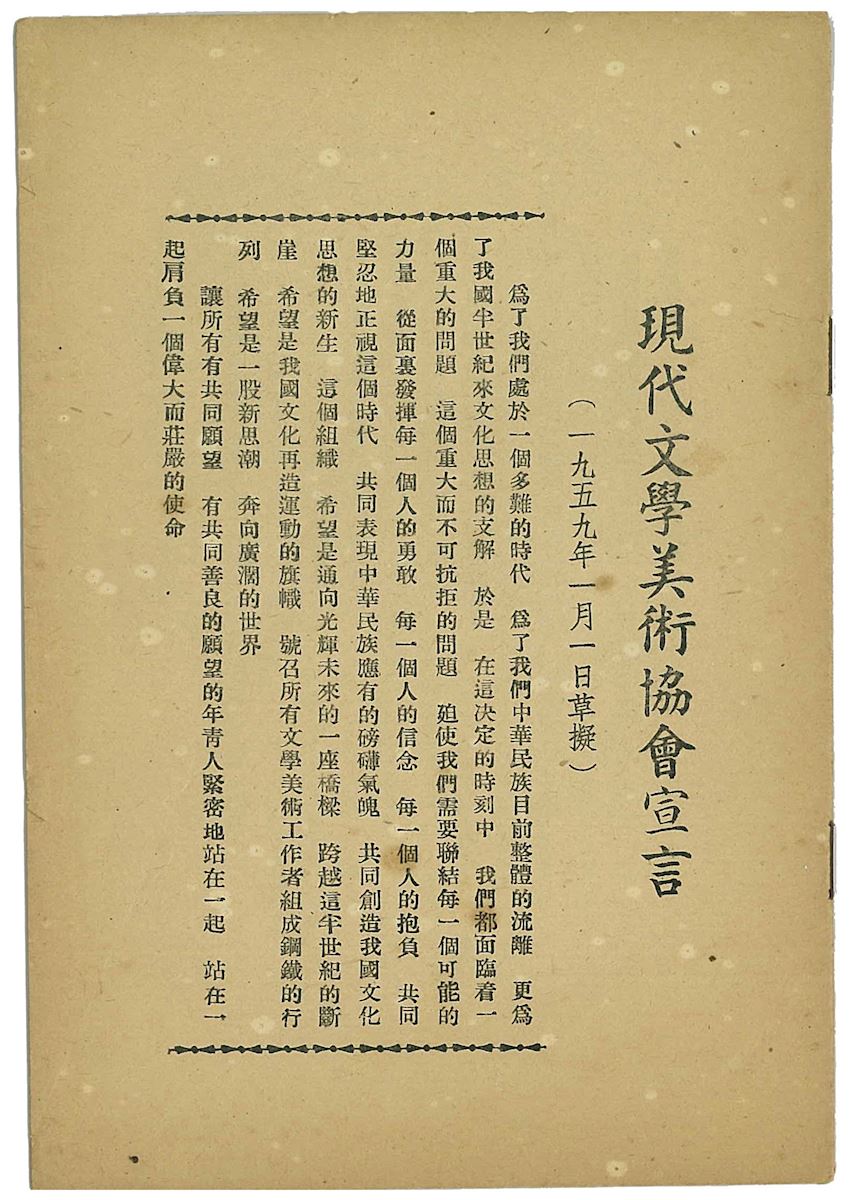

▲ “Manifesto of The Modern Literature and Art Association Hong Kong” (Facsimile)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

(1).jpg)

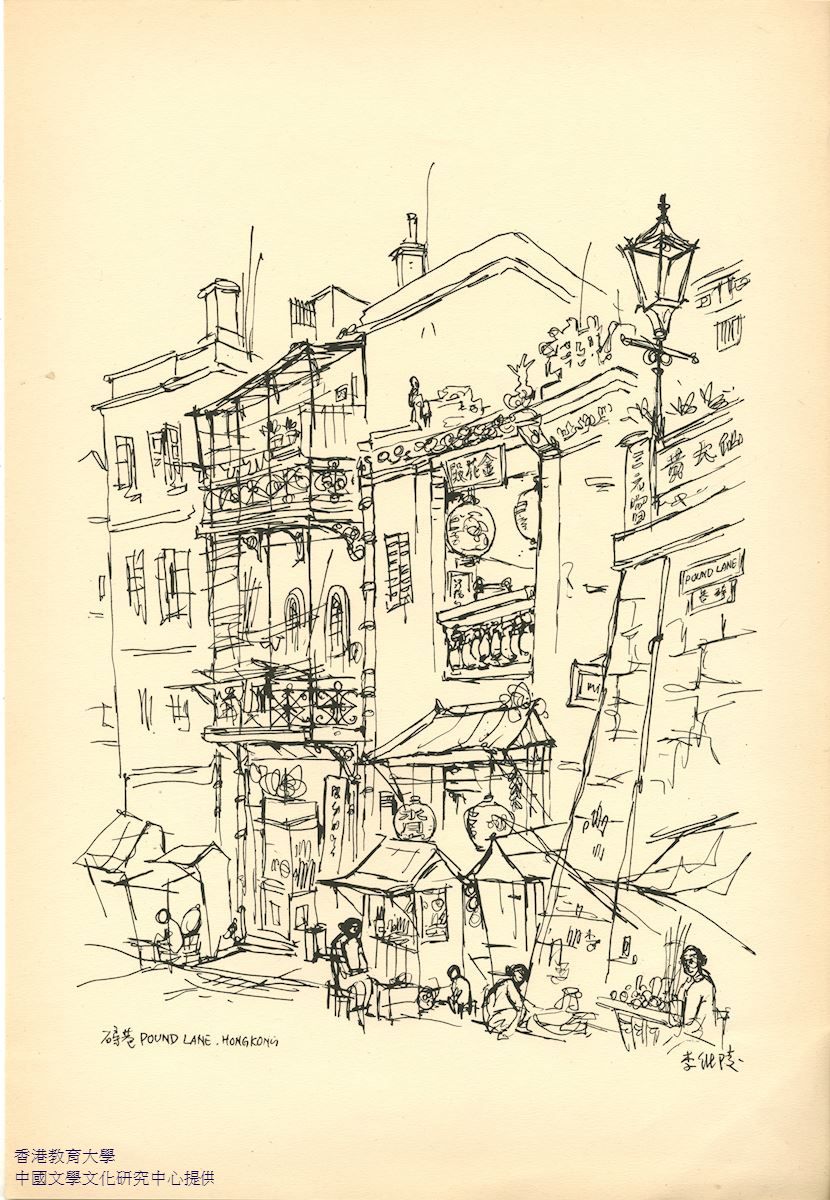

▲ “Li Wei-Ling’s Paintings” / Hong Kong: Dazong Publication / 1975

▲ Lau Yee Cheung's The Drunkard

Stories of Hong Kong Literature

Q:Writer Li Kuang was the chief editor of Everybody's Literature in the 1950s, and his poetry collection was republished several times due to its popularity. Born in Guangzhou, his indissoluble bond with Hong Kong was established back in the 1930s due to the red bean paste which cost three cents a bowl ...

A:

Li Kuang fled to Hong Kong in the 1930s when he was a middle school student, and could only afford a bowl of red bean paste that cost three cents at Sham Shui's Po Pei Ho Street. To him, paying twenty cents for a bowl of Guiling Jelly was too expensive, and it also could not change his preference.

The taste of red bean paste made him dream of Hong Kong streets, the trams, the Peak, and even brought him back to Hong Kong. In the 1950s, he was the chief editor of Hong Kong's literary publications, Everybody's Literature and Hai Lan, and wrote a poetry collection: "Yan Yu", "The Bells in the Highland", etc. He was one of only a handful of poets who had their poetry collection republished. In 1958, he moved to Singapore, devoting himself to teaching, and once again bade farewell to Hong Kong.

27 years later, he returned as a visitor. Even though people had changed, his feelings for Hong Kong remained unchanged. He wrote in "Three Hong Kong", "I nod, I'll definitely return to Hong Kong, and the next time when I "return to Hong Kong", it will not be after 27 years, but at most one to two years later. I will write "Yi Dong" again, and once gain have tea in Central, and take the tram and ferry. Next time, I will not be so unfamiliar with Hong Kong." Unfortunately, there was no next time, as he died in Singapore on the Christmas Eve of 1991.

Q:Hong Kong writer, Shu Xiang Cheng's novel, The Sun has Set, describes the daily life of Hong Kong. Why was the novel renamed Behind the Streets of Hong Kong Island when it was published in China in 1984?

A:

Shu Xiang Cheng is an important Hong Kong writer, and his novel, The Sun has Set, is one of his masterpieces. This novel was first serialized from January to October 1961 in Nanyang Literature magazine, and the first edition was published in the following January by Nanyang Literature Publications.

In January 1979, Hong Kong Literature Research Institute republished the book. In the early 1980s, with China's reform and opening up, Hong Kong literature gradually caught the attention of mainland Chinese scholars. Guangzhou's Flower City Publishing House planned and selected some important Hong Kong literary works for publication, and The Sun has Set was one of them. It was published in October 1984, but as "Sun" symbolizes Chairman Mao it was thus "taboo"; the book title was renamed Behind the Streets of Hong Kong Island. It was said that the author lamented over it.

In October 1999, Hong Kong's Arcadia Press Ltd. rearranged and published the book, and listed it as one of "Shu Xiang Cheng's Fiction Collection". In June 2008, it published the Commemorative Edition of The Sun has Set.

Changing the book's name from The Sun has Set to Behind the Streets of Hong Kong Island reflects the helplessness of that generation; it witnessed the ubiquitous influence that politics has on literature.

Q:Hong Kong writer, Leung Ping-kwan, recalled that he first read the poems of another Hong Kong writer Ma Lang, when he was 14 years old. He "discovered" this poet from Selected poems of the Sixties published in Taiwan ...

A:

I "discovered" Ma Lang's (Ma Bo Liang) poetry in the early 60s.

In 1962, the fourteen-year-old Leung Ping-kwan borrowed Selected poems of the Sixties, published in Taiwan, from Hong Kong City Hall Library, and got to know Hong Kong writer Ma Lang and his works. The following year, he read from an old magazine, Literary Current Monthly Magazine, about Ma Lang's North Point, the place where the poet grew up:

One night, as I was strolling nearby, I saw someone selling old books beside a chess group lit with a kerosene lamp. Among the pile of old books on "pastry", "blue book" and astrology, I saw a stack of old magazines called Literary Current Monthly Magazine, which cost only two cents per copy, so I quickly bought them.

At that time, it was only four to five years after the discontinuation of Literary Current Monthly Magazine. In the past, Hong Kong's Chinese education did not pay much attention to, or preserve, current literature. Literary youths could only "discover" Hong Kong literature through informal channels, and literature has always relied on such profound methods to be passed down and inspire beginners.

In 1983, Leung Ping-kwan recalled this "discovering" experience in Ma Lang's "The Loafer who Burns the Piano".

Q:The movie In the Mood for Love, starring Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung, was directed by Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai. Do you know which Hong Kong writer’s novel the movie is based on?

A:

You may have watched the movie, In the Mood for Love, directed by Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai, but do you know that the movie is related to Hong Kong's literature?

The novel Intersection of Hong Kong writer Lau Yee Cheung was the inspiration for In the Mood for Love. Besides honoring the novelist in the movie closing credit, some lines from Intersection were particularly quoted at the end of the movie. Although it was not a direct adaptation of the book, the moving story where literature and movie were interwoven and went beyond the restrictions of time and media, induced thoughts and imagination of the audience. The interaction of a novel published in 1972 and a movie released in 2000 created a Hong Kong story in 1960.

The subsequent movie, 2046, was under profound influence of another novel of Lau Yee Cheung, The Drunkard. The Drunkard was written in the early 60s, and was known as "China's first stream of consciousness novel", and a classic work of Hong Kong literature. Wong Kar-wai subsequently produced In the Mood for Love and 2046, both of which were inspired by Lau Yee Cheung's works, showing that the text was so fascinating that it captured the director's heart.