A Taiwanese "Just So" Story|Doomsday Flood|Disastrous Wind|Shadows Under the Water|The Mountain's Lost Souls

The early settlers of Taiwan faced a myriad of life-threatening challenges that ran the gamut from torrential rains and winds to earthquakes, landslides, and floods. Nature was a petulant and unforgiving fact of everyday life that weighed heavily on the minds of those who came to make a new life here. Thus, it is only natural that these threats and dangers would occasionally be personified and woven into stories that caught on and were shared from generation to generation.

The best-known local legend about earthquakes is that of the Di Niu (subterranean bull). Also, Taiwan's Austronesians have legends of earthquake-causing giants and wild boars. All of the indigenous tribes have legends related to floods. The traditional Chinese tale of the Deng Hou (Lamp Monkey) also touches on popular fears of floods great enough to cover the land and submerge islands. Popular stories have regularly and imaginatively credited natural disasters to gods, demigods, and other supernatural beings. Rivers, providers of life, can also take life and wreak devastating havoc. Thus, the ghosts and ghouls that reside in these waters require rituals to keep them from causing mischief. Many a trek through mountain forests ended in travelers becoming disoriented and losing their way. Thus, stories arose of forest goblins that lay in wait in the deep woods, ready to send passersby to certain doom.

Settlers on this strange and unfamiliar island put their imaginative stamp on the dangers around them. Personifying these dangers made them things that could be dealt with, appeased, resisted, and even possibly eradicated.

A Taiwanese "Just So" Story

Taiwan, within the Pacific Ring of Fire, is regularly rocked by seismic activity. Each of the island's different Austronesian groups have somewhat different stories about the origin of earthquakes. One story that certainly predates the arrival of Chinese settlers says that the land is held up by animals, which set off earthquakes when they need to scratch an itch.

Inō Kanori's article "Jishin ni kansuru Taiwan Doban no Kōhi" (Earthquakes in the Traditions of Formosan Aborigines) relates that Atayal tradition holds that earthquakes occur when a giant hornet stings the carp that lives beneath the earth and that the Beinan tribe on Taiwan's East Coast believe that earthquakes happen when the one-armed, one-legged being who is holding up the earth gets sore and shifts position. Further, the Basay of the Taipei Basin attribute earthquakes to a boar beneath the earth turning from one side to the other. Interestingly, Inō Kanori found the theme of the Di Niu (subterranean bull) to be woven through both Austronesian and Chinese earthquake mythologies. In facing the awesome, destructive power of earthquakes, the people on Taiwan hoped not only to identify the cause of this phenomenon but also to construct rituals that might mollify or even control the entities responsible.

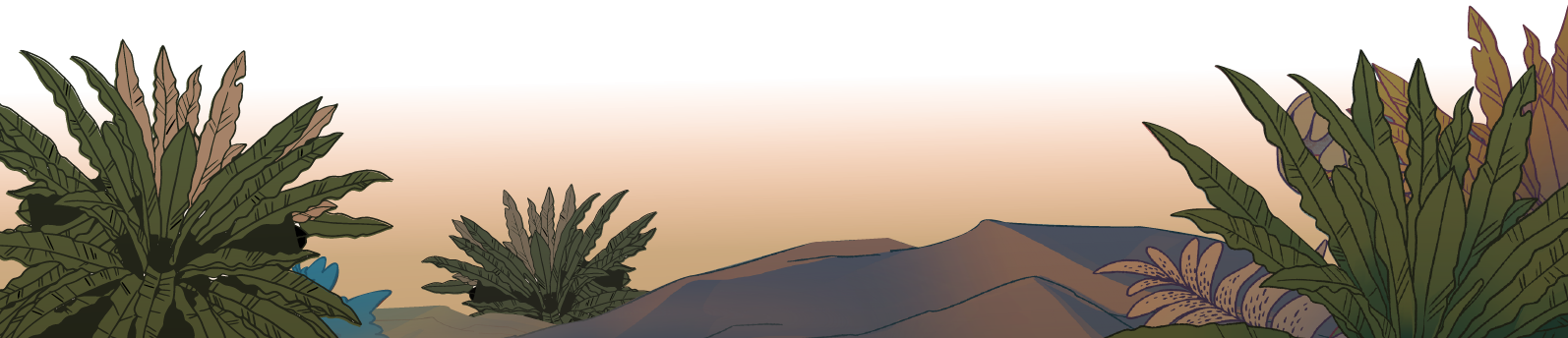

Di Niu

Source: "Jishin ni kansuru Taiwan Doban no Kōhi" (Earthquakes in the Traditions of Formosan Aborigines), by Inō Kanori, in TŌKYŌ JINRUI GAKKAI ZASSHI (JOURNAL OF THE TOKYO ANTHROPOLOGICAL SOCIETY), issue 241, vol. 21, 1906.

The mythical Di Niu or "subterranean bull" features in both Austronesian and Chinese legends about earthquakes. Chinese legends attribute small tremors to the bull's fur standing on end, minor earthquakes to the bull flapping its ears, and strong earthquakes to it swishing its tail. Thus, earthquakes are sometimes referred to as a bull "turning over" or "scratching an itch". In a similar vein, the Bunun tribe of central Taiwan say that earthquakes happen when the giant bull-like animal living under the earth rises to its feet. The Tsou have a legend that is similar to the Bunun's.

Doomsday Flood

Flood myths are not uncommon among the various indigenous tribes of Taiwan, which perhaps reflected the actual memories of the land's ancestors. Among these myths, some tell of an animal - perhaps a gigantic eel or snake - blocked the river, causing the water to rise; some relate that the water-gulping monster shut its mouth, causing the river to overflow; some say it was the god's punishment for breaking a taboo; some say the sea god was displeased with the maid offered; and still others say that it was an attack by the sea god on the other gods. In these myths, the people were devastated by the flood. In their struggle to survive, many stories related to the origin of fire also came about.

The Chinese people in Taiwan also wove their worries about flooding into their New Years' legend of "The Lamp Monkey's Complaint to the God of Heaven." In these ancient myths, it is not hard to find hidden traces of mythical creatures and spiritual beasts from prehistoric times.

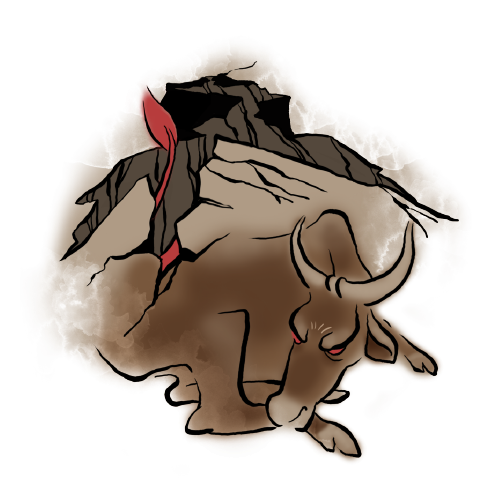

Tarovar

Source: THE MYTHS AND TRADITIONS OF THE FORMOSAN NATIVE TRIBES by Ogawa Naoyoshi, 1935.

In THE MYTHS AND TRADITIONS OF THE FORMOSAN NATIVE TRIBES, there is a legend about the Kapaiwanan flood, which tells of a monster called Tarovar living on the flatland and the river water that flows into its mouth. One day, Tarovar's mouth was clogged, causing the water level to rise and, eventually, causing a flood that spared only Tomapalapalai Mountain, Wutou Mountain, and Dawu Mountain. Only when Tarovar finally opened its mouth again did the flood subside.

Lamp Monkey

Source: "Anger of the Lamp Money", GO-EN by Gao Rong-wu, 1932.

TAIWAN MINKAN BUNGAKU-SHŪ (COLLECTION OF FOLKLORE FROM TAIWAN) records the story of the lantern monkey from Dakekan. Traditionally during the winter solstice, people stick glutinous rice balls onto furniture in appreciation of the furniture deities' hard work. However, the "Lamp Monkey" deity on the lamp stand was somehow left out. Flying into a fit of rage, the Lamp Money scampered to the heavenly court and framed humanity with all manner of crimes. Believing its words, the Emperor of Heaven decided to flood the earth at the end of the year and destroy all humans. Fortunately, the pleading of other deities let mankind survive.

Disastrous Wind

Wind is the natural flow of air, and due to the differences in terrain and environment, wind appears in ever-changing forms, giving rise to all kinds of personified legends. In Taiwan's indigenous myths, wind sometimes symbolizes vitality, and stories about women becoming impregnated by the wind are not uncommon. Although bringing good, there is also a cruel side to wind, as related in the Pazeh legend of "Apu-bare" (the Wind Lady).

In the Pazeh legend, wind is described as originating from below ground in a cave where Apu-bare lives. When Apu-bare opens the cave entirely, a violent storm is released, causing catastrophe. The end of this legend is also a metaphor for the conflict between humans and Mother Nature. Another example is Taiwan's foehn winds, which scorches plants as if by fire or some evil force. A poem by a Qing Dynasty writer describes the foehn winds as a "qilin storm" with destructive power. According to the book, TAIWAN FŪZOKUSHI (TAIWAN MANNERS AND CUSTOMS), a bird called the "Stone Swallow" lives in remote mountains and faraway islands. When it soars and swirls skyward, it stirs up the air between sky and earth, creating the winds.

Apu-bare (Apubari; the Wind Lady)

Source: MYTHOLOGIES OF UNDOMESTICATED SAVAGES by Sayama Yukichi & Yoshitoshi Onishi, 1923.

According to the legend of the Pazeh people, there is a gigantic cave in the northern mountains where wind originates. Inside this cave lives "Apu-bare", who has control over the magnitude of the wind by the extent to which she opens the cave. Apu-bare has a lump on her head, so she had to leave the cave occasionally to catch the sun. One day, she fell sound asleep and did not return to the cave for several days. As a result, strong winds continuously blew from the mouth of the cave, causing the people to suffer terribly. Finally, a brave warrior killed Apu-bare with an arrow and broke into the cave to destroy all of the doors and windows. Since then, the winds blowing from the cave have become significantly milder.

Shadows Under the Water

The story of humanity is closely intertwined with water. While water is essential to life, it is also a font of calamity and sorrow. The torrential rains and frequent typhoons of summer send rivers roiling across their banks and onto fields and villages. The frequency of extreme weather here has injected dire warnings on the dangers of open water and rivers into Taiwan cultural traditions and stories and fueled the proliferation of tales about water-dwelling ghosts, ghouls, and other related phenomena.

Water-related folk traditions and practices permeate every corner of Taiwan. The dragon-boat races held during the late-spring Duanwu Festival represent perhaps the most widely observed of these. Although now claim a story of tragic romance as the origin of these races, they may indeed be rooted in a much older tradition of river worship and rites held to stop waterborne illnesses.

Observances are also regularly held around Taiwan in remembrance of particularly devastating floods. In Kouhu, Yunlin County, the 'Spirit Drawing out of Water' ritual memorializes the thousands who died in an 1845 flood. Yilan County's Pài-Poh Ritual seeks to placate the anger of drowned souls and secure the levees with prayers of peace to Laodagong and the Water God. These and other similar religious rites around the island reflect the general public's fear of water.

Shui Gui (Water Ghosts)

Source: "The Water Ghost's Promotion to City God", TAIWAN NICHINICHI SHIMPO (TAIWAN DAILY NEWS), Sep. 1st, 1917 (6th year of Taisho era).

Water ghosts are imagined to be the spirits of people who have drowned and, in order to achieve reincarnation, must find another soul to take their place. Thus, water ghosts are always at the ready to pull an unsuspecting victim under the water. Water ghosts are the most prominent ghost archetype in Taiwan. The colonial-era newspaper Taiwan Nichinichi Shinpō (1898-1944) frequently ran spine-tingling tales of water ghosts and their mischievous doings. While most are portrayed as unequivocally evil, some water ghosts have been said to be unwilling to harm the living. An instance of the latter is the foundation of the folk tale "The Water Ghost's Promotion to City God".

The Mountain's Lost Souls

While humans rely on the rich resources in the mountains and woods, they also fear the dangers hidden within. Mountains effuse a mysterious power that has never failed to amaze people since ancient times. The most widely spread stories are none other than people losing their way in the mountains in all sorts of strange ways. In the Atayal story cited in the MYTHOLOGIES OF UNDOMESTICATED SAVAGES, a young girl went collecting firewood one night, and was lured into the deep of the forest by a black hand. She was later found in a tree by tribal members and remained mute ever since.

Stories about "people being pulled by evil beings to places that are hard to reach," may be seen by Chinese as the works of "Môo-sîn-á" - a monstrous being surprisingly similar to indigenous versions of devils such as "Saraw" and "Lalimenah". The commonness of these mountain legends and commonality across different ethnic groups reflect the shared awe and respect of the mountains.

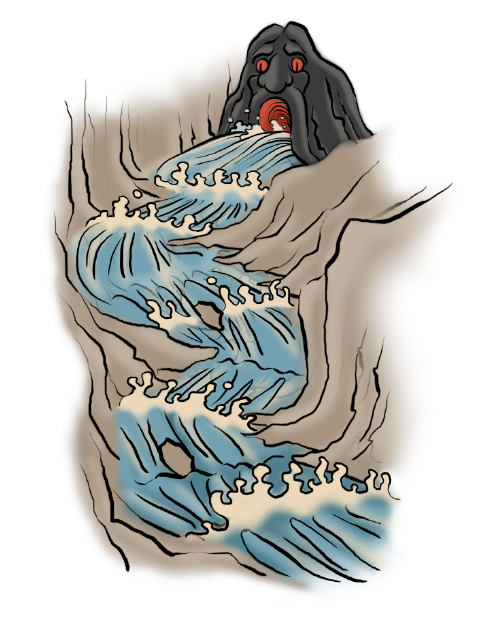

Môo-sîn-á (the Demon)

Source: "Mountain Demon", HAN DAILY NEWS No. 2947, February 1908.

Môo-sîn-á appears in mountains and forests, and often lures people into the mountains by guile. This demon is also known as "Moxin" and "Mosina", and the Hakkas call it "Wangxin". Once deceived by a Môo-sîn-á, its victims lose their mind, and when fed with grass, mud, or dead bugs will find this food delicious. The earliest written description of Môo-sîn-á was recorded in TAIWAN NICHINICHI SHIMPO (TAIWAN DAILY NEWS) in 1908.

Lalimenah

Source: BANZOKU KANSHŪ CHŌSA HŌ KOKUSHO (AN INVESTIGATION OF THE CUSTOMS OF THE ABORIGINES IN TAIWAN) Volume II.

Lalimenah is an evil spirit in Sakizaya legend that lures sleeping persons to a faraway place, makes them take a wrong path or climb to the top of a tree, or stuffs their mouths with cow dung, grass, branches, or bugs. According to another version of the legend, Lalimenah is the image of the God of Death. Lalimenah can transform itself into the visage of a person who has passed away and speak to the sick, who will then die a few months later.

Saraw

Source: BANZOKU KANSHŪ CHŌSA HŌ KOKUSHO (AN INVESTIGATION OF THE CUSTOMS OF THE ABORIGINES IN TAIWAN) Volume II.

Saraw is an evil spirit documented by both the Amis and Puyuma peoples. Saraw lives in the mountains and is as tall as the sky. It will catch humans and hide them in the mountains. According to BANZOKU CHŌSA HŌ KOKUSHO (INVESTIGATION OF THE SAVAGE PEOPLES) REPORT, Saraw appears in March, and makes passersby forget their intended destinations. Its victims may wander for several days, climb high into a tree, or sit by flowing waters in a trance. Those bewitched by the Saraw may be found in places that are normally difficult to reach or even found dead.

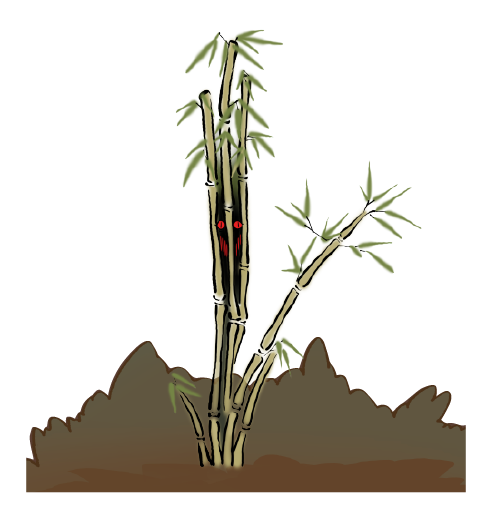

Bamboo Ghost (Tek-ko-kui)

Source: MINZOKU TAIWAN (TAIWAN FOLKLORE) Volume IV, Issue 8.

The Bamboo Ghost, also known as Zhugui, Zhuzigui, or Zhugangui, appears at dusk according to a Hakka legend recorded in the COLLECTION OF HUALIEN COUNTY FOLKLORE. It will manifest in the form of a bamboo stalk and lie across the road. If someone accidentally comes across it, it will bounce up suddenly and draw away the person's soul. In another version, the Bamboo Ghost pummels passing pedestrians, hurting or even killing them. To drive the Bamboo Ghost away, one should curse it and force it to give way, or apologize to it sincerely and ask it to allow safe passage. There is another monster also known as the Bamboo Ghost. It is ten meters tall and often follows behind a person. When encountering this monster, one should pluck a frond of Chinese silver grass (Miscanthus) and pull off the foliage while chanting "I'm long and you're short, I'm long and you're short." This will cause the Bamboo Ghost to steadily shrink in size.