The Hand That Rocks the Cultural Cradle|Exploring the Frontiers of Mortality

Tales of the paranormal in part draw upon the general desire for there to be explanations beyond the mundane. Beyond satisfying their physical and material needs, humans desire spiritual satisfaction. What reality doesn't provide, we humans have shown ourselves more than capable of filling in the blanks. For example, the natural human desire to someday reunite with departed relatives and friends, an impossibility in the physical world, becomes possible in the spiritual. Existence after death, spirits, and other otherworldly phenomena play out in this unseen realm and, perhaps, give those still caught in reality a sense of inner peace.

This nonmaterial sating of spiritual needs goes beyond individual needs to encompass social needs. Society's occasional thirst for nonmaterial explanations or diversions nourishes and perpetuates the entire paranormal genre.

Ghosts reflect our imaginings of the hereafter and address a fundamental spiritual need. Moreover, the intermingling of the afterlife with the preexistence supports and encourages a system that is both holistic and ethical. From this perspective, ghosts may be a piece of the social landscape that society simply cannot do without.

Ghouls, on the other hand, tend to appear to address apparent social needs, underscore specific moralistic points, reign in proscribed behaviors, vent feelings of guilt, or foster internal cohesion. Thus, although at first blush it may seem that ghosts and ghouls exist only as evil entities intent on vexing humanity, they have in fact had an important, behind-the-scenes role in keeping things in balance, both at the level of the individual and of society.

So, what purpose does stories of the paranormal serve? The answer may be simply that ghost, ghouls, and other such creatures of the night fill a human need. The paranormal may be a social lubricant that helps keep us steady in the face of the unknown and maintains social harmony. Their stories give us a window on the culture of our forebears and on how they lived, thought about their world, and formed and transmitted collective memories.

The Hand That Rocks the Cultural Cradle

Don't Open the Door!|Monsters Who Prey on Children |The Summoners

There are all kinds of paranormal beings lurking in the shadows of every society. Some are just frightening, while some are more destructive. But all are daunting, as they are believed to be able to cause harm. However, the origin of these fears may be more human than paranormal. When a society cannot cater to the spiritual needs of its residents, people began to create imaginary creatures responsible for havoc in order to maintain normal societal operations. Conversely, the corresponding behaviors of these created beings will further reinforce the beliefs of the people.

For example, some hauntings are associated with long-term illness or natural disasters. When bad things last for a long time and are unsolvable, they can make people suffer, and without faith in believing that things will eventually turn out fine, the sufferers will not be able to hang on. In such situations, by attributing the disasters to the doings of evil beings who are ultimately subduable by gods, disasters enter the operational framework of society, becoming issues that are handleable. In other words, humans create hope for the future through their beliefs in these trouble-making creatures.

This is only one form of haunting. In Taiwan, both the indigenous people and the Chinese have legends related to myriad kinds of hauntings. Giving thought to the social significance of these hauntings may give a whole new perspective to their meanings, and make people rethink their relationship with the paranormal beings in this scientifically advanced generation.

Don't Open the Door!

Regardless of the period of history, the 'stranger' has always been a source of foreboding and fear. Add to this scenario children at home alone who unwittingly let the stranger inside, and you have fodder for a classic tale of terror. The large families that typified traditional Chinese households up to recent times meant that a stranger could very likely gain admission by pretending to be a distant uncle or aunt. "Grand Aunt Tiger" is a story in this vein.

Grand Aunt Tiger is a classic Taiwan-Chinese fable that keeps listeners on the edge of their seat and delivers a moralistic sermon at the end. Taiwan's indigenous cultures have stories with a similar plot, including the Beinan tribe's Grandma Bear, a Truku tale about a child-eating demon, and the Paiwan story of a ghoulish creature known as the "Sariku". While the similarities may show the fingerprints of cultural borrowing or reflect a universal literary theme, these stories in both Chinese and Austronesian contexts illustrate the predictably terrible outcomes earned by straying beyond accepted social mores and rules and warn the children in the audience to keep to 'the straight and narrow.'

Hu Gu Po (Grand Aunt Tiger)

Source: "Grand Aunt Tiger" by Morimoto Junko, in MINZOKU TAIWAN (TAIWAN FOLKLORE), vol. 2, no. 2, 1942.

Grand Aunt Tiger was a Taiwanese fable told to children in nearly every household. It tells of a tiger goblin of the mountain forests that took on the appearance of a kindly old lady and tricked two young sisters into letting her inside their home, where she felt sure she would enjoy a hearty feast once they were asleep. This tale, long known throughout China, came with the Chinese who emigrated to the island. Related stories appear in colonial-era publications including Kareitō Minwashū (A Collection of Taiwanese Folktales ) and Minzoku Taiwan (Taiwan Folklore).

Sariku

Source: MYTHOLOGIES OF UNDOMESTICATED SAVAGES by Sayama Yukichi & Yoshitoshi Onishi, 1923.

In the MYTHOLOGIES OF UNDOMESTICATED SAVAGES, there is a story about Sariku told by the Paiwan Kasuga tribe, which says that "Sariku" forced its way into the house of two boys when they were alone at home and told them interesting stories to make them fall soundly asleep. In the middle of the night, the elder brother woke up and heard Sariku eating. He asked what Sariku was eating and Sariku panickily replied "cowpeas." The elder brother realized his younger brother had been eaten, and quickly hid in a tree. He poured hot lard from the tree down onto Sariku when it came after him, scalding the monster to death.

Monsters Who Prey on Children

In ancient times, when medical science was less developed, newborns and infants who died prematurely were sometimes believed to have been taken away by deities or evil creatures. Chinese sometimes gave their children ungraceful pet names, or raised boys as girls in a society that is partial to boys. The purpose of belittling children was to tell evil beings or deities that "this child is not worthy of being taken away." Also, people might ask a deity to adopt their weak and sickly child as a godchild, so that the child may be blessed with good health and grow up safely.

However, despite meticulous care, some newborns and infants still die young. In such cases, blaming the death on the doings of evil spirits would relieve people from guilt and reduce disorder in the community. In the Amis legend Alikakay, the Giant Child Eater impersonates a person to take babies away and eat their innards. The Kaxabu people's Fanpo Ghost (Huan-pô-kuí) is able to remove and eat babies' innards without breaking the skin. The Chinese also have a legend about a cat ghost that loves the smell of sesame oil chicken soup, a dish commonly served for women during their confinement for convalescence after giving childbirth. The cat ghost is lured by the aroma, and chokes babies to death. The passing down of such legends of baby-killing monsters simply reflects a means of facing the fear that people have toward the early death of newborns and infants.

Cat Ghost

Source: HAI YIN POETRY by Liu Jia-mou, Provincial Documents Committee of Taiwan.

It is a Taiwanese folk-custom to hang a dead cat on top of a tree to prevent "cat ghosts" from causing trouble. It has been passed down from ancestors that if a dead cat is buried in the ground, it will soak up the essence of heaven and earth and transform into a cat ghost. A cat ghost will hurt people, especially babies. The folk custom of making offerings to "cat ghosts" in Taiwan was described in HAI YIN POETRY by Liu Jia-mou.

Fanpo Ghost (Huan-pô-kuí; daxedaxe)

Source: TAIWAN'S LOCAL LEGENDS.

According to the legend of Puli's Kaxabu people, Fanpo Ghost is an evil sorcerer who practices black magic. She is able to fly by placing banana leaves under her armpits and to see at night by exchanging eyes with a cat. Fanpo Ghost loves food with a fishy smell, and will steal tribal members' fish and children's hearts to eat. When injured by an arrow or gun, the wound of the Fanpo Ghost will fester but she will not die until she sees the arrow or gun that shot her.

The Summoners

In facing difficulties, societies sometimes turn inward to seek out enemies onto whom blame can be pinned. The process of rooting out and publicly punishing 'enemies' is a way of venting built-up social anxiety and, in some cases, of restoring social cohesion. In social psychology, this is known as the 'scapegoat' phenomenon. In being publicly fingered and accused as the culprit, the scapegoat not infrequently admits to the wildest of claims, such as shapeshifting into a demon, in order to end the terror of the inquisition. Such forced confessions may have been the origin of more than a few ghoulish legends. Different from socially accepted shamans and sorcerers, those suspected of weaving magical spells in private or of being able to conjure up and control demonic beasts earned the fear and condemnation of the community. Thus, individuals consigned to this latter category became natural candidates when scapegoats were needed. Atayal folklore tells of a conjurer able to command bird demons. Minzoku Taiwan (Taiwan Folklore) preserves a Chinese folktale about a golden goblin that brings fortune to its master in return for a diet of human flesh.

Are there really people who are able to summon up ghoulish beasts? The 'scapegoats' never make positive claims of their own. It is those around them … those in need of a convenient enemy … who speculate, spread rumors, and make accusations. Whatever the ultimate truth of the matter, the endings of these folk stories are never pretty for those who are able to conjure up demons and monsters. The fingered scapegoat is always sacrificed to restore social stability.

Golden Goblin

Source: "Golden Goblin" by Satoshi Miyayama, MINZOKU TAIWAN (TAIWAN FOLKLORE) Volume II, No. 2, 1942.

It is said that if a person worships the Golden Goblin, it will work and earn money for him or her. In return, the person must present the Golden Goblin with a human as an offering every year. Although worshipping the Golden Goblin will make one rich, most who do so do not enjoy a happy life. Based on the literature from the Japanese Colonial Period, Golden Goblin was actually a housemaid who turned into a restless spirit after being tortured to death. She worked for her master when alive and continued to do so after her death. However, surveys show that this story may be a variant of the legend of the poisonous golden silkworm (Jincan gu).

Bird of Calamity

Source: "Matori" (Devil Bird) by Haruo Satō, in SHOKUMINCHI NO TABI (A JOURNEY IN THE COLONIES).

'Devil birds' are birds that are purportedly summoned and controlled by Atayal wizards. Those unlucky enough to see one of these powerful birds was said to be marked for certain death. The Atayal treated such conjuring as a serious taboo and anyone fingered as raising a 'devil bird' would be put to death along with his or her entire family in order to squelch any possibility of future reprisals. Although this bird has been described as a white pigeon with red talons, a one-legged bird covered in red plumage, and other combinations of colors and characteristics, we know today that 'devil bird' is a homophone of the Atayal word for 'incantation'. Thus, the devil bird is likely the imagined manifestation of tribal black magic.

Exploring the Frontiers of Mortality

The Wandering Ghosts|Lonely Maidens on the Prowl|The Austronesian Afterworld

The line between life and death may be less clear than we imagine. Both Austronesian and Chinese cultures on Taiwan have perspectives that are rooted in religious beliefs on the world that awaits us all after death. Rather than a hazy, indistinct landscape, the afterlife has clear social structures with clear divisions between good and evil and fairly meted out punishments and rewards. Assurances that things do not end at death and that sins known and unknown would be paid in full on judgement day have been effective at keeping social order in the mortal realm.

For Chinese, ghosts are the form that the souls of the departed assume to interact with the living. Thus, ghosts are extensions of life and worthy of assistance and normalization. One example is provided by the folk traditions surrounding the helping of orphaned (unremembered) souls and the souls of unmarried women to end their earthly wanderings and enter into the 'normal' realm of the afterlife.

Most of Taiwan’s indigenous tribes hold a belief in some sort of spiritual realm that departed souls travel to and live in after death. However, tribes differ greatly on the location of this realm, with the perspectives of each reflecting their unique ideas about the world.

The Wandering Ghosts

In Taiwan's traditional beliefs, the concept of "ghost" is not clearly defined. It may lie between god, ghost, and ancestor depending on whether it is being worshiped or not after death. In the SPRING AND AUTUMN ANNALS, it is written that "a ghost who has a home will not turn into a vengeful spirit." If a person is being worshiped after his/her death, which means becoming an ancestor of the family, he/she will enjoy a peaceful life in the underworld. On the contrary, those not worshiped, such as unmarried women* or those who die in a foreign land, will become wandering ghosts. Some wandering ghosts desiring to be worshiped will "haunt" or "show their presence or do some miraculous display" in order to attract worshippers and have temples built for them. These temples are known as ghost temples.

Paying respect to these wandering ghosts enables ghosts and humans to coexist in harmony. This gave birth to the Pudu ceremony held during the ghost month each year, which allows hungry ghosts with no one to worship them to have a sumptuous meal. But some people remain fearful of these wandering ghosts and thus invite the "Lord of All Spirits" or Zhong Kui to the Pudu ceremony as a further measure to keep wandering ghosts from harassing the living.

* In Chinese tradition, a woman who dies unmarried is not worshipped by her family, as she is not considered part of the family lineage.

Dashiye

Source: "The Chronology of Folk Customs and Festivals", CHIAYI INTERNAL INTERVIEW BOOK, Provincial Documents Committee of Taiwan.

Dashiye, also known as the "King of Ghosts," is a deity in the underworld charged with managing the souls of the dead that is worshiped by both Buddhists and Taoists in Taiwan. In the Ghost Festival ritual during the 7th lunar month, people pray to Dashiye for an "uneventful" ceremony. In Chiayi's Minxiong Township, Dashiye Temple is dedicated to Dashiye. The reason why locals worship Dashiye is described in detail in the CHIAYI INTERNAL INTERVIEW BOOK.

Lonely Maidens on the Prowl

The prevalence of female ghosts in Taiwanese stories and fables reflects contemporary social structures. Traditional Chinese society is patriarchal, and marrying a daughter was invariably seen as a step that was necessary for her to fulfill her life's purpose as a daughter-in-law and mother. Daughters who didn't marry had no place in the social order. They weren't written into the family genealogical list and would not be prayed for by future generations. Thus, their fate was sealed as wandering, forlorn ghosts after death. Even women who married into a family but not as a first wife and who did not bear a son would not be remembered in death. Furthermore, girls who died before having the opportunity to marry were said to become wandering spirits known as 'lonely maidens'.

Stories such as these added to traditional pressures for girls to marry when the opportunity arose. However, women weren't without a workaround to such a grim 'providence'. In death, female ghosts could disturb the dreams of and stir trouble among the living in hopes of drawing attention to their plight and directing strangers and familiars alike to dedicate prayers for them at temples. Family members could also dedicate a memorial tablet for her at one of the many temples that are consecrated to the souls of unmarried women. A family could even arrange a posthumous marriage for their daughter, which earned for her a name and prayers in the host family's genealogical record.

Sister Lintou

Source: TAIWAN FŪZOKUSHI (TAIWAN MANNERS AND CUSTOMS) by Kataoka Iwao,1921.

The tale of Sister Lintou, Tainan's most famous female ghost, has been in circulation since the 18th century. In life, 'Sister Lintou' was a widow with sons and daughters. However, she was taken advantage of by a heartless grifter and left penniless. After her children died of starvation one after another, she ended her life by choking in a noose tied to a stand of thorny pines (lin tou). In death, her ghost wrought havoc on her home village until a fengshui master intervened. He helped send her on a journey to find and rain revenge upon the man who had destroyed her family's life. Taiwan's colonial-era 369 TABLOID, Kataoka Iwao's TAIWAN MANNERS AND CUSTOMS, and Higashikata Takayoshi's TAIWAN SHŪZOKU (TAIWANESE CUSTOMS) all included stories related to Sister Lintou.

Chen Shou-niang

Source: HAI YIN POETRY by Liu Jia-mou, Provincial Documents Committee of Taiwan.

Chen Shou-niang was a chaste lady during the reign of the Daoguang Emperor in the Qing Dynasty who became a bitter ghost after she died tragically. It is said that Chen Shou-niang lived near the entrance of Jingting Alley in Tainan (today's Beimen Road) and was the wife of Lin Shou. After the death of her husband, her mother-in-law and sister-in-law urged Chen Shou-niang to remarry, which she resolutely refused. In the end, she was tortured to death by both of them. She became a ghost and haunted the village. This incident was documented by Liu Jia-mou in HAI YIN POETRY.

The Austronesian Afterworld

Taiwan's Austronesians have a view of the afterlife that differs starkly from that of the Chinese. While the Chinese afterlife is ordered and bureaucratic, many indigenous tribes see existence after death as differing little from that during life, aside from its location on a different plane. Moreover, tribes and even villages conceptualized the afterlife differently from one another. Colonial-era books Banzoku Kanshū Chōsa hō Kokusho (An Investigation of the Customs of the Aborigines in Taiwan) and Banzoku Chōsa hō Kokusho (Investigation of the Savage Peoples) report that the Amis of the Pacific Coast believed that villages of the dead were located somewhere in the eastern skies and that those who did evil in life lived with dogs and cats in death. The residents of Falangaw Village, in the vicinity of today's Taitung City, held that the spirits of the dead went to the sun. One group of Atayal related that departed tribe members went to live along a cliff somewhere in the west and, although they believed in this village of the dead, they were unsure as to its actual location. Most of Taiwan's Paiwan believed that souls found rest on their sacred mountain Mt. Beidawu, while most Tsou believed their ancestors went to Mt. Tashan. Still other village communities, while believing in spirits, had no beliefs in an afterlife. The widely diverse perspectives on death and the hereafter encapsulate well the inherent diversity that defines Taiwan's different Austronesian groups.

The White Rock of Mt. Tashan

Source: BANJIN DŌWA DENSETSU SENSHŪ (COLLECTION OF ABORIGINAL FOLKTALES) by Yasushi Senoo & Suzuki Tadasu, 1930.

Tsou legend says that the souls of their dead travel to Mt. Tashan. One Tsou romantic fable is set at the boundary between life and death in Laiji (Pnguu) Village at the foot of this mountain. The story goes that a couple had just married when the husband died in a sudden accident. The spirit of the bereaved young wife's husband appears before her and leads her to Mt. Tashan (Hohcubu), where they live together in the village of the dead and raise a family. Indigenous stories such as this starkly distinguish Austronesian conceptualizations of the afterlife from those of the Chinese.

Spirits in the Physical Realm

Source: THE FORMOSAN NATIVE TRIBES: A GENEALOGICAL AND CLASSIFICATORY STUDY by Utsurikawa Nenozo, Mabuchi Tōichi, Miyamoto Nobuhito, 1935.

Chinese tradition holds that souls go to the underworld after death. However, some indigenous tribes believe that the afterworld exists in our physical world. For example, the Rukai believe that when one dies, his/her soul will return to the sacred land of Kariyalra, a dense forest between Dalupalringi and Taidrengere, to become one of the ancestral spirits. In the legend of "Princess Balenge," which tells the story of a human and a hundred-pace viper falling in love, the viper reveals that it is the king of Dalupalringi and thus may actually be the king of the spiritual world.

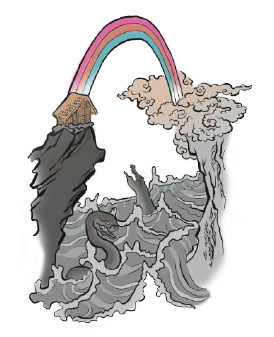

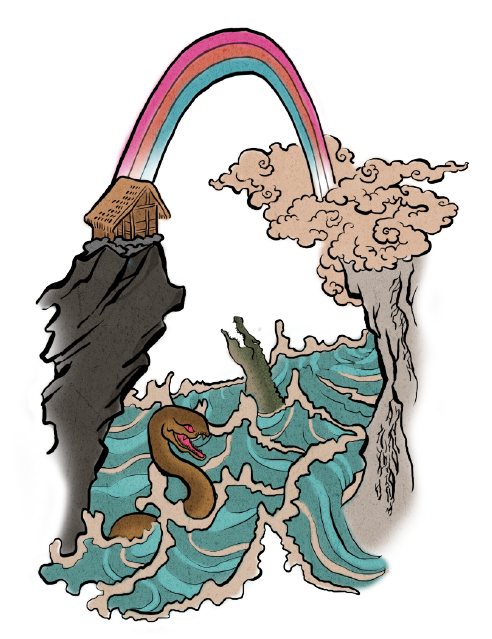

Abyss Bridge and the Monsters Under the Bridge

Source: BANZOKU CHŌSA HŌ KOKUSHO (INVESTIGATION OF THE SAVAGE PEOPLES) REPORT by the Special Taiwanese Custom and Practice Research Board, Government-General of Taiwan, 1915.

Indigenous beliefs regarding the afterworld differ from those of the Chinese. Moreover, different tribes have different legends. The Atayal believe that when a tribal member dies, he/she has to cross hongu' utux (the Bridge of the Spiritual World), which is like a rainbow in the sky, to reach the spiritual world. Men who had killed enemies and women who were skilled at weaving are welcomed by their ancestors in the spiritual world. Others less accomplished would not be able to enter the spiritual world and may even be eaten by the monsters under the bridge - like the kbibing monsters in the Nan'ao branch legend of the Atayal.