A Room of One's Own or Passing Through the Wilderness|Sparks of Gender Movements Appeared Before the Advent of a Greater Wave of Gender Awareness|Factories and Brothels: Women That Were Forgotten|Guide to Female Power

In 1949, many female writers followed the Nationalist government to Taiwan. These new-generation intellectuals, many of who had participated in the May Fourth Movement, all had unique areas of specialization and helped broaden the literary landscape for female writers in Taiwan. In the dark days of authoritarianism, these women towed the official line and wrote within the theme of "fighting communism to save the country." Most of their writings indeed resonated with the plight of the country. Yet, in the meantime, their self-consciousness also increased as they attempted to challenge the patriarchy and express concern about the status of women through their writings. This was the first wave of women's literature in Taiwan.

A Room of One's Own or Passing Through the Wilderness

In 1955, the Chinese Women Writing Association was founded and joined by many famous writers, including Su Xue-lin, Zhang Xiu-ya, Dong Zhen, Meng Yao, Pan Ren-mu, Lin Hai-yin, Chung Mei-yin, Liu Mu-sha, Xie Bing-ying, and Chi Chun. The association had over a hundred members.

The following year, the Chinese Women Writing Association published A COLLECTION OF WOMEN'S WRITINGS. On the surface, the book was dedicated to "adhering to the Three Principles of the People, continuing the fight against the Chinese Communist Party and Russia, and forming a troop of writers." However, the writings differed from the large-scale narratives about the country's predicament, as they mostly focused on the complicated frame of mind faced by writers after undergoing the war and settling in Taiwan.

These female writers had more freedom in the unique time and space of this important era. They were also more capable of thinking about family power dynamics, which helped open a new chapter in the advance toward gender equality in Taiwan.

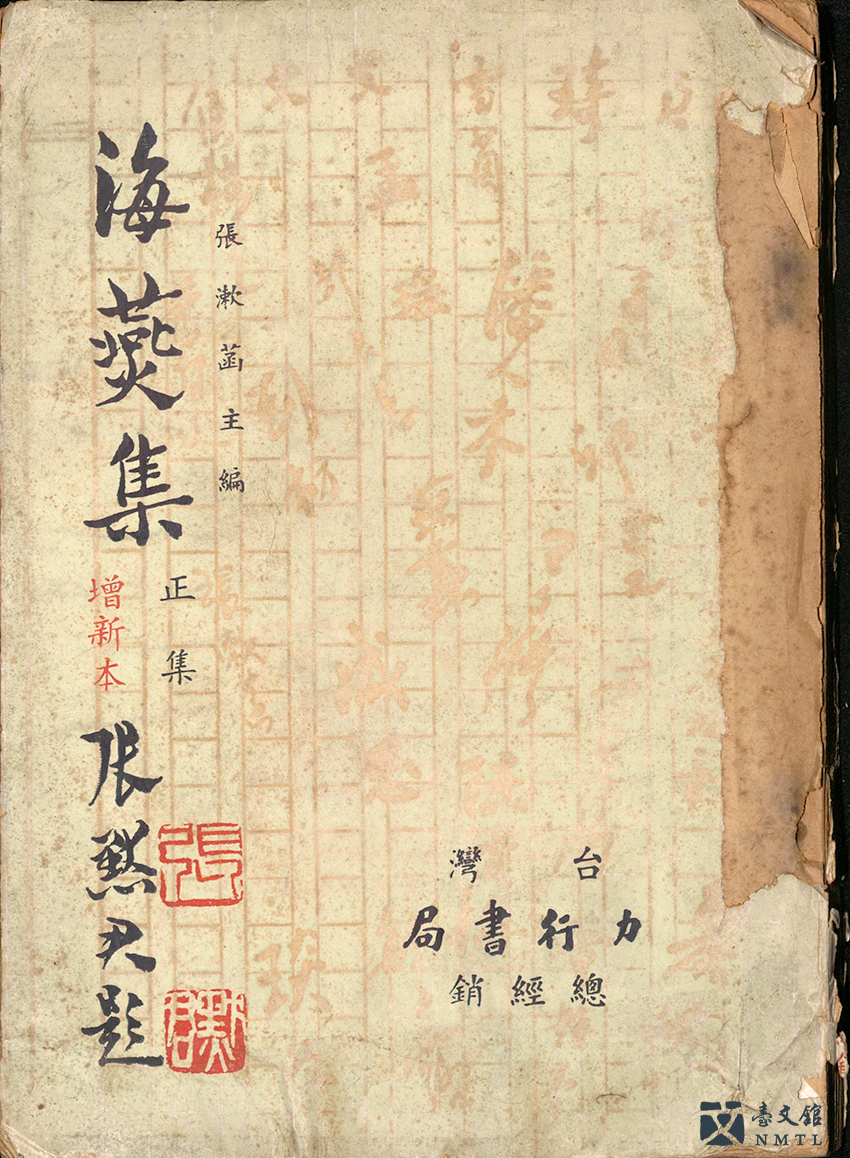

► PETREL COLLECTION

In 1953, writer Zhang Shu-han gathered works by Su Xue-lin, Zhang Xiu-ya, Kuo Liang-hui, Ai Wen, and Pan Ren-mu as well as her own works into a book called PETREL COLLECTION. It was the first collection of female writings in Taiwan. The display is the edited version published in 1959. (Donated by Cui You-ming / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

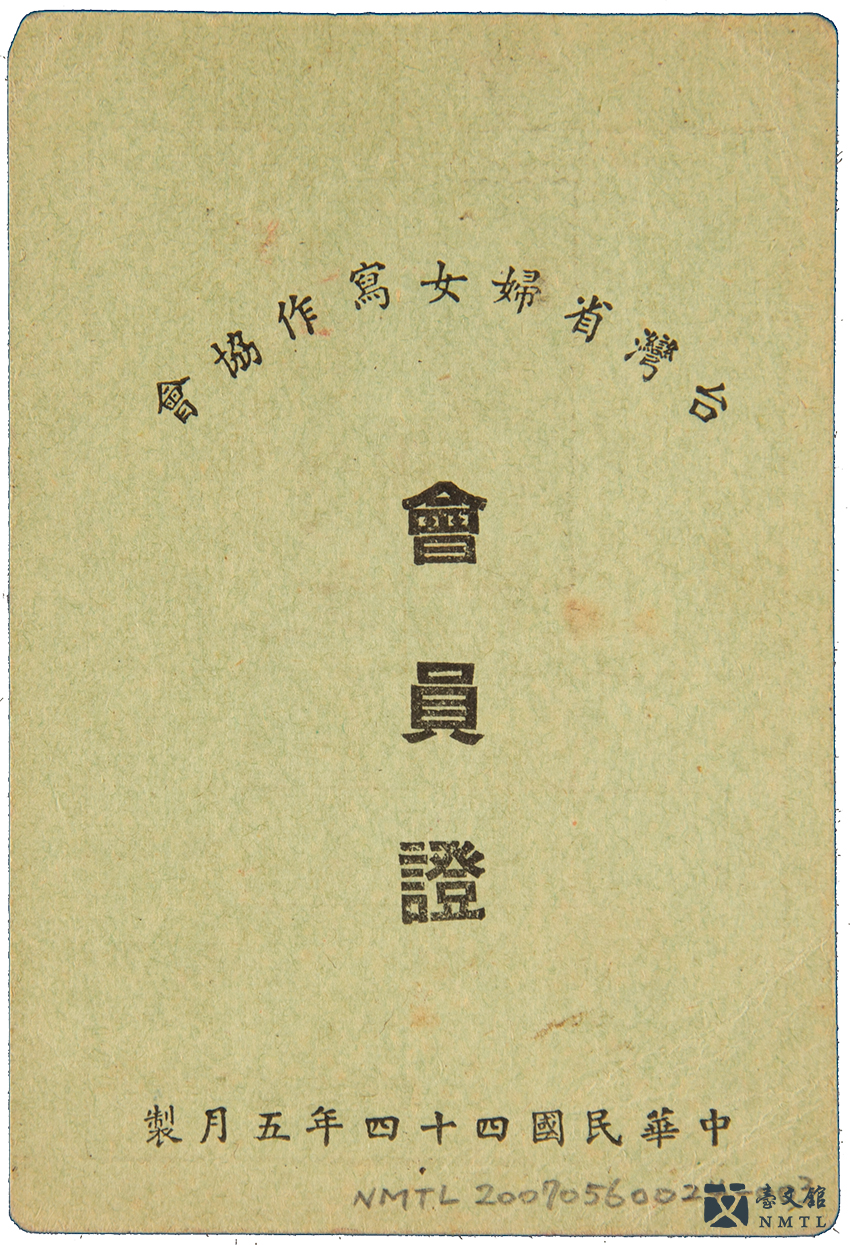

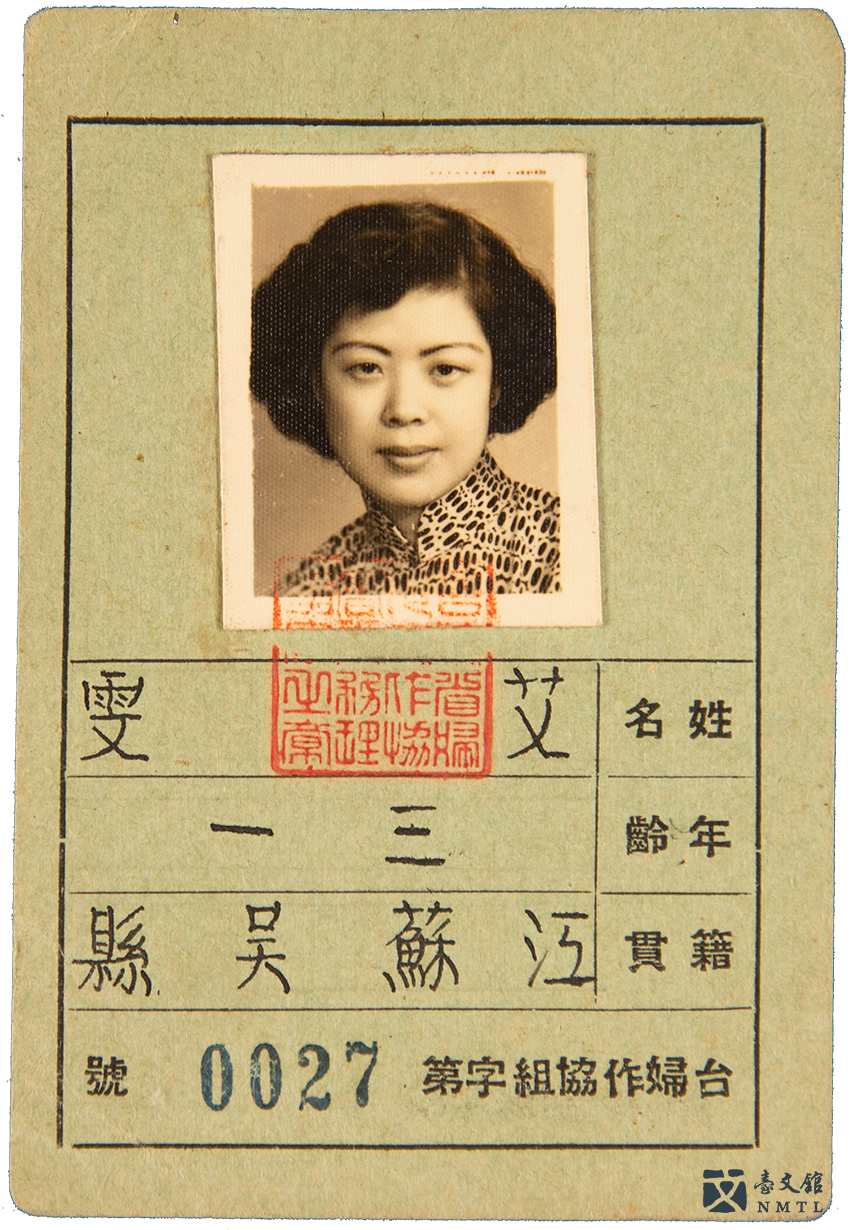

► Taiwan Women Writing Association Membership Card

Writer Ai Wen's Taiwan Women Writing Association Membership Card. Produced and Issued in 1955. (Donated by Ai Wen / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

► The 1st Chinese Women Writing Association Literature Awards: Senior Editor Award

Writer Pan Ren-mu's Senior Editor Award of The 1st Chinese Women Writing Association Literature (1996). (Donated by Dang Ying-tai / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

► Translator's Foreword

A manuscript written by Zhang Xiuya following her 1973 translation of Virginia Wolf's A ROOM OF ONE'S OWN. (Donated by the family of Zhang Xiu-ya / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

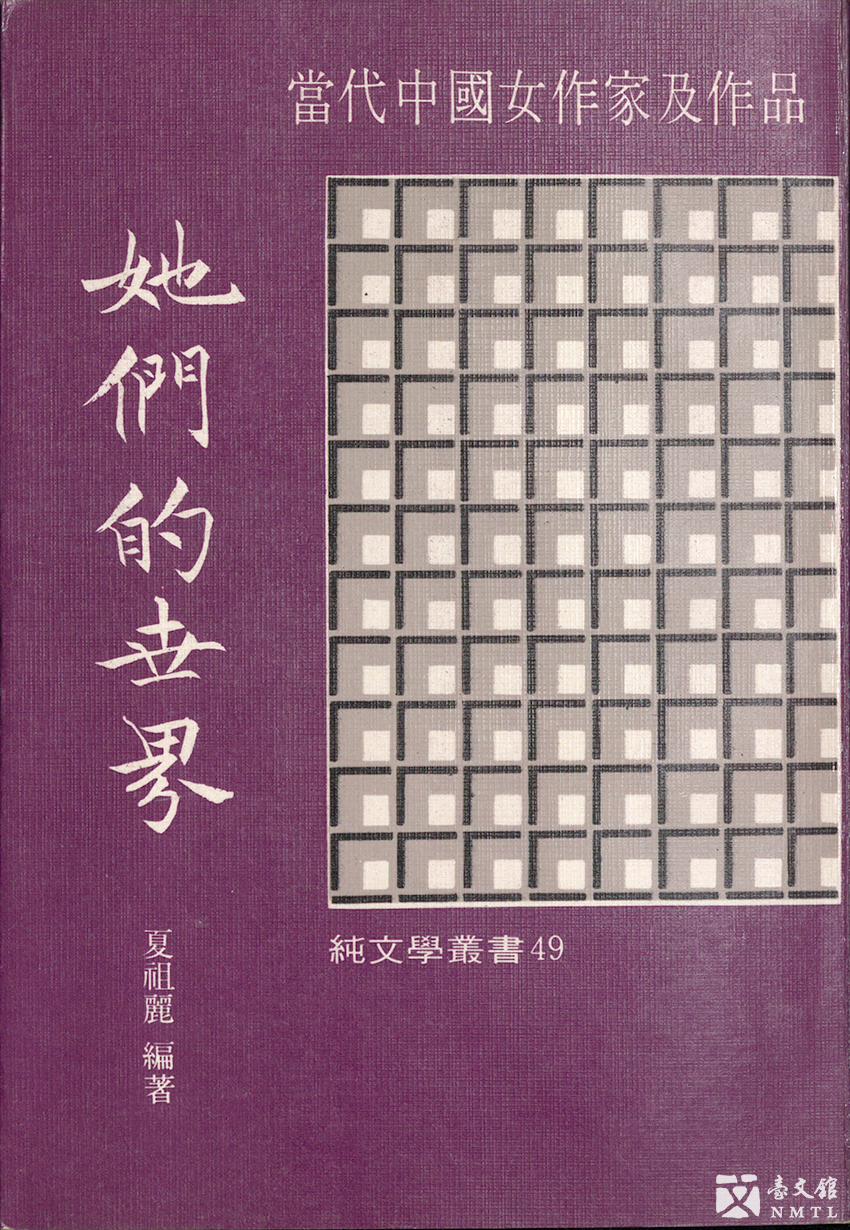

► THEIR WORLD

The book cover of THEIR WORLD: CONTEMPORARY CHINESE FEMALE WRITERS AND THEIR WORKS. This was published by Pure Literature Publishing House, founded by Lin Hai-yin in 1968. The editor Xia Zu-li is Lin's daughter. The book is a collection of Xia's interviews with female writers conducted over a two-year period beginning in 1970 for WOMEN'S MAGAZINE. It also features the writers' works. (Donated by Xia Zu-zhuo / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

How nice it is that he's not home. Only at this time do I feel that I belong to myself and I can do whatever I want. …He is not going to eat at home, so I can dress up and go out. Does he also "dress up for the person he admires?" Who admires him, except for me? I will just let him be, in case he complains he has lost his freedom as a man. That eternal freedom enjoyed by men.

I don't have to cook. That's nice. It's like women are only alive because their sole purpose is to cook and give birth to children for men. What exactly are you complaining about, woman?

──Wang Ling-xian, "How Nice It Is That He's Not Home," 1968.

⁍ Wang Ling-xian's "How Nice It Is That He's Not Home" depicts a wife's utterly complicated mindset. Her husband is out wining and dining clients, while she stays at home alone. She is free momentarily, since she does not need to do chores. Yet, she is still thinking about her husband. Her mind is still shackled by her family. Is this momentary freedom true freedom for women?

Sparks of Gender Movements Appeared Before the Advent of a Greater Wave of Gender Awareness

In the 1960s and 1970s, the authoritative government was still suppressing political dissidents. Gender awareness was like plum trees in the winter, persistently waiting to bloom again.

In 1962, Kuo liang-hui's HEART LOCK was published, which boldly challenged the boundaries of traditional morality. Although it was immediately banned by the literary world, discussions about it continued. Erotic literature was like warm air flowing beneath the façade of conservatism. In 1969, Lin Hwai-min's "Cicadas" was published. The following year, he wrote "Winter of André Gide," the modernist language of which hides messages about homosexuality. In 1977, Pai Hsien-yung's CRYSTAL BOYS was published in installments. His readers were introduced to unvarnished portrayals of furtive homosexual affections and family conflicts. At the same time, Lu Hsiu-lien encouraged women to challenge tradition through writing and publishing, and attempted to promote the postwar feminist movement to the outside world. New ideas about gender sporadically appeared before the advent of a greater wave of awareness about women's rights.

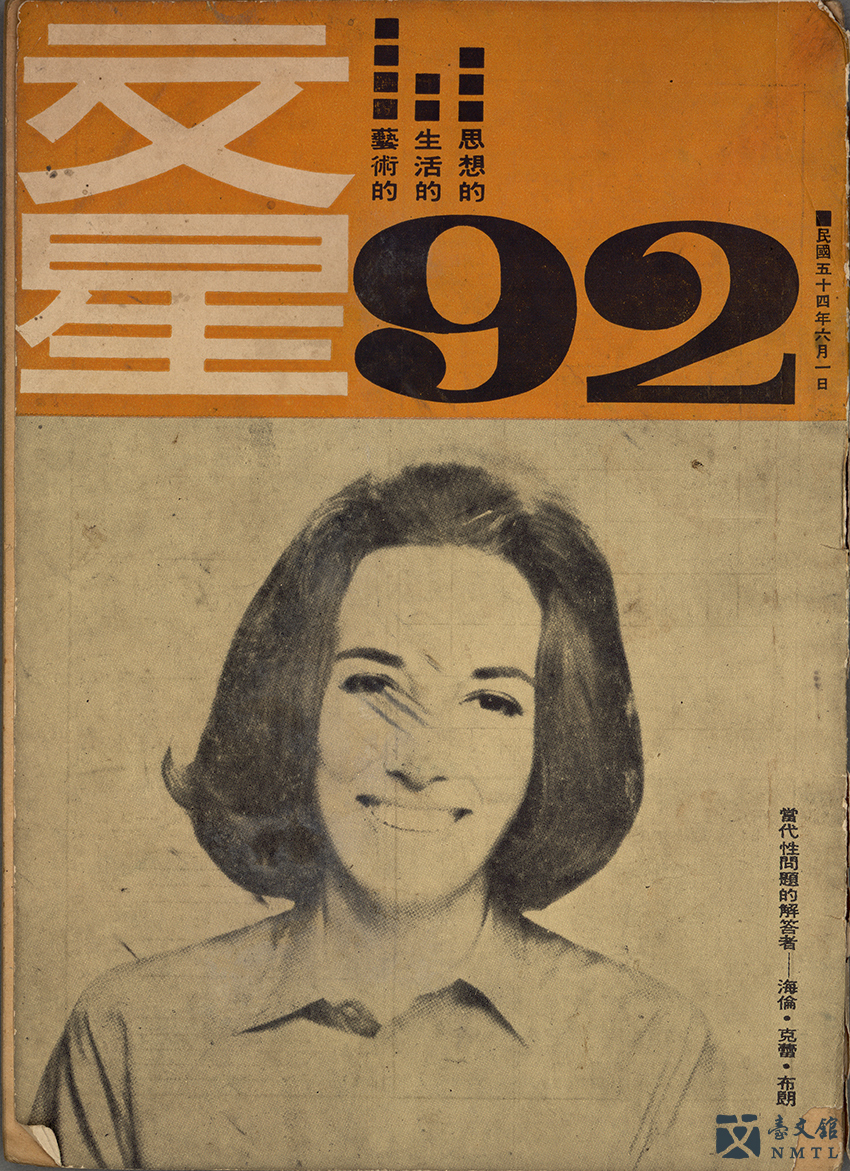

► LITERATURE STAR, Issue 2, Vol. 16

The 92nd issue of LITERATURE STAR in 1965. This issue features Lu Xiao-zhao's article "From 'Heart Lock' to 'Jade Nude'," which discusses literary and artistic freedom and claims that the government should not have banned these two books. (Donated by Lin Jui-ming / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

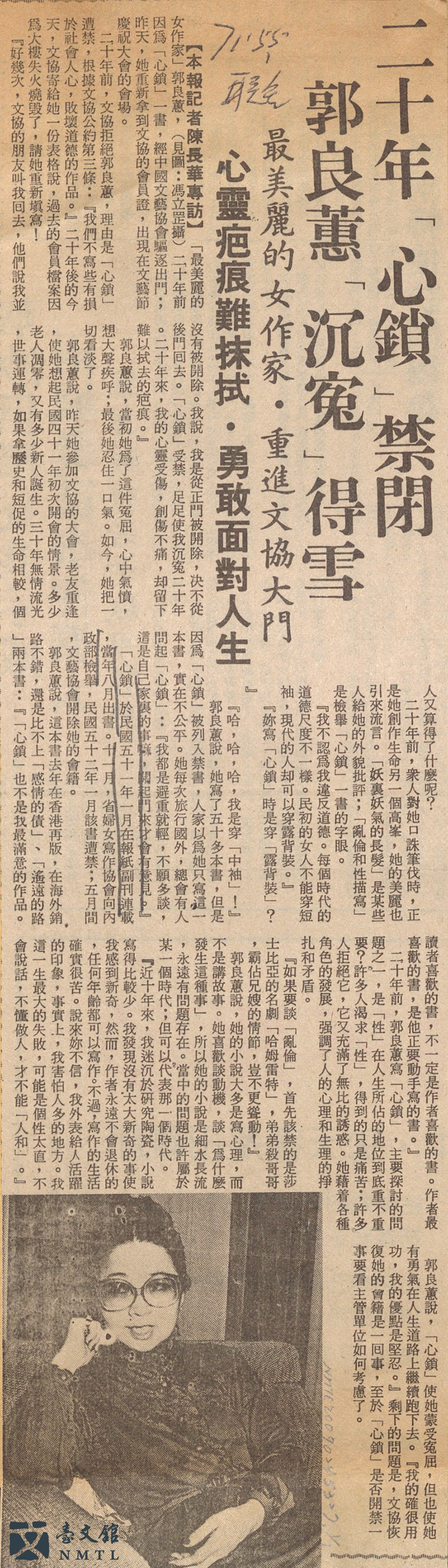

► Newspaper Clipping of "Kuo Liang-Hui's 'Heart Lock' Finally Unbanned After 20 Years"

Chen Chang-hua's interview published in the May 5th, 1982 edition of UNITED DAILY NEWS. The article once again stresses that the story "Heart Lock", which was published 20 years ago, mainly focuses on whether sex is important in life and that the author wanted to draw attention to the psychological and physical struggles and conflicts through the development of each character. (Donated by Jiang Mu (Muye) / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

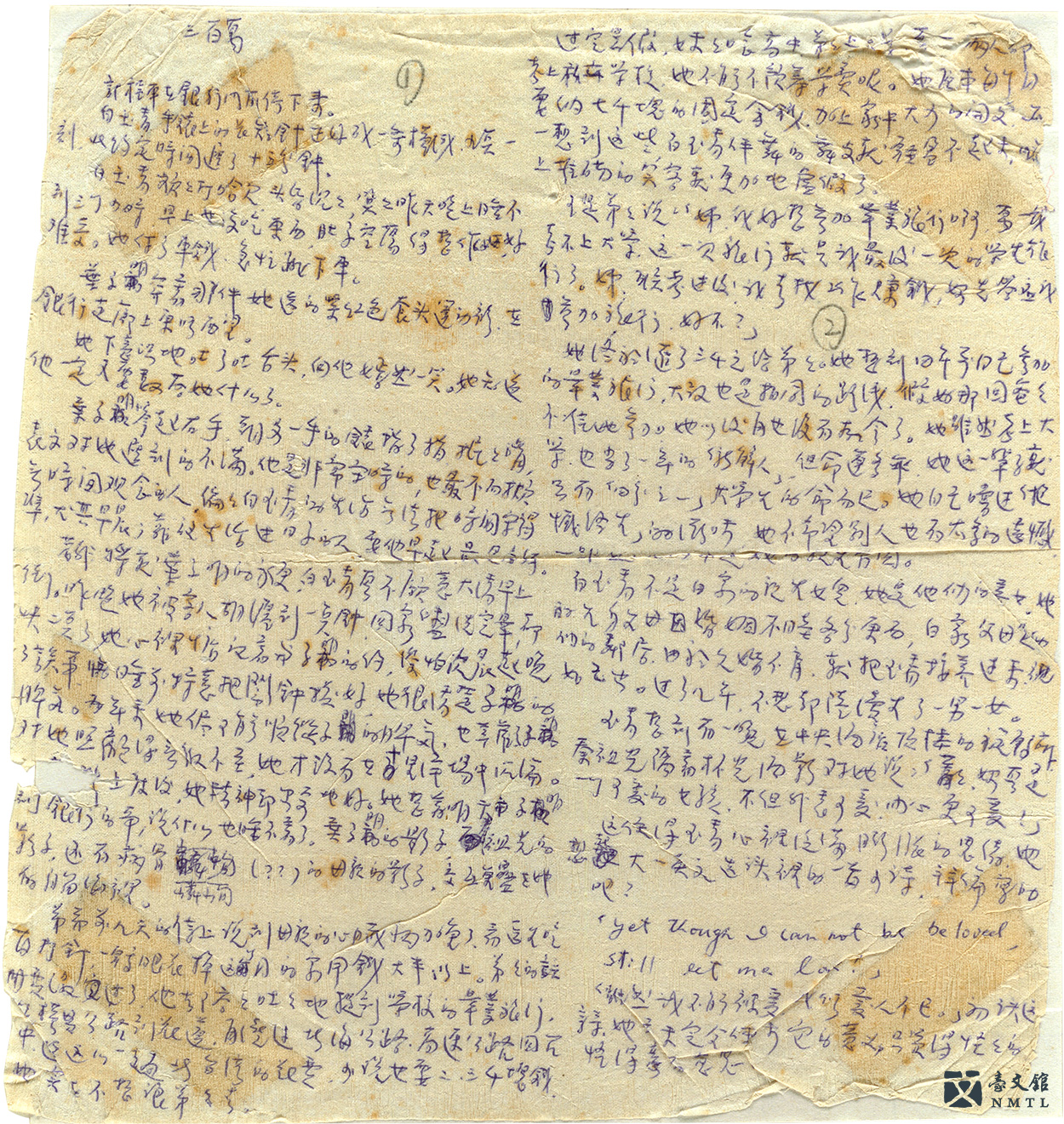

► Manuscript of "Three Million"

After the Formosa Incident in 1979, Lu Hsiu-lien was given a sentence of jail time and was released in 1985. During her jail time, she used tissue paper to write novels. Four sheets of her "tissue paper manuscripts" have been restored and kept by the National Museum of Taiwan Literature. "Three Million" was the book published later on, THE STORY OF THREE WOMEN, featuring three women who are classmates at university. The women confide with one another about their stories during their separate life journeys. (Donated by the family of Zhang Xiu-ya / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

Three months and ten days ago, on an unusually sunny afternoon, my father threw me out of the house. The sunlight pouring into our alleyway turned everything white. With bare feet, I tried hard to run all the way to the end of the alleyway. When I looked back, I saw my father chasing after me. His towering figure was shaking with one hand brandishing that gun he once used when he was a regimental commander in China. His grey hair stood on end and his bloodshot eyes emanated rage. His voice, filled with indignation, trembled, and he yelled in a hoarse tone: You bastard! Bastard!

──Pai Hsien-yung, CRYSTAL BOYS, 1977.

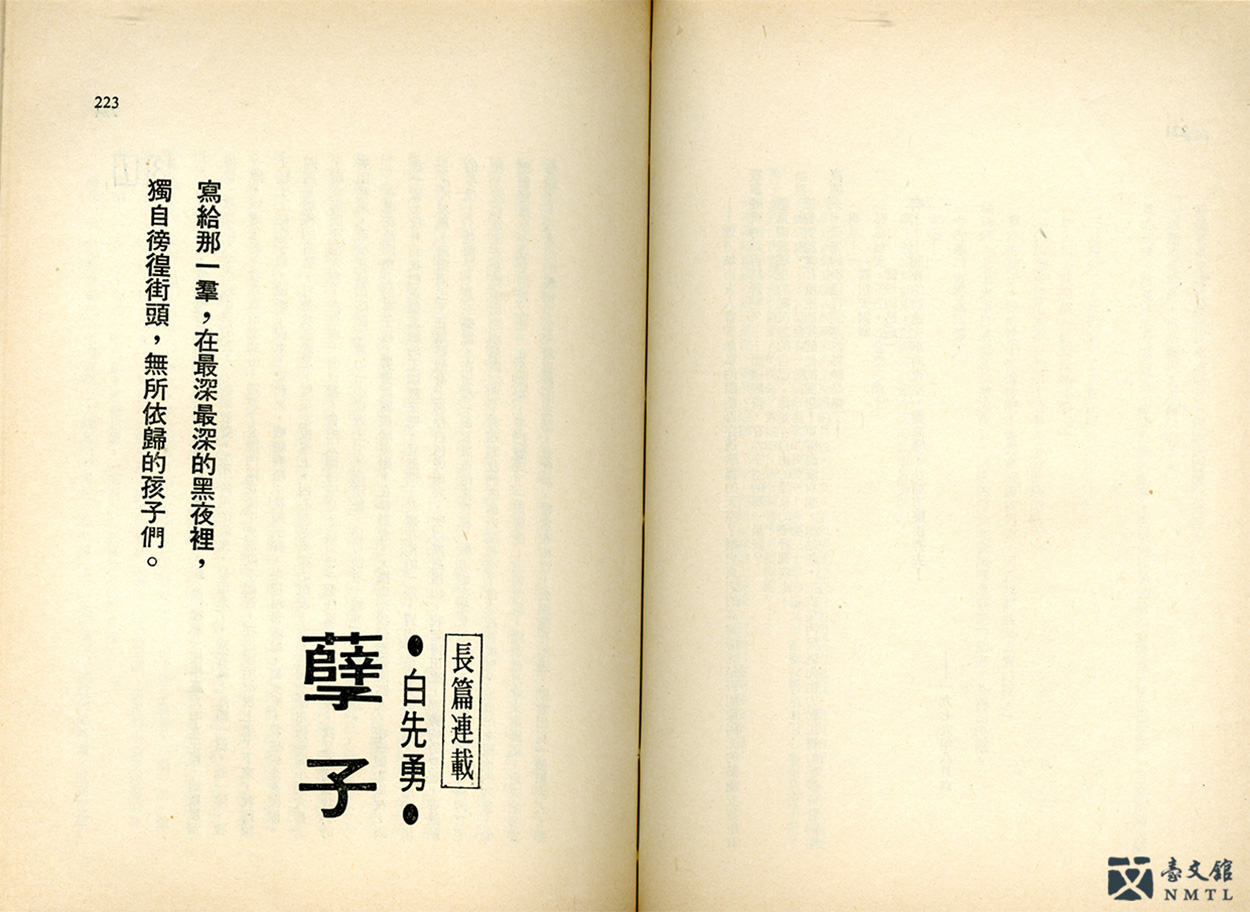

⁍ Pai Hsien-yung's CRYSTAL BOYS was not the first queer novel in Taiwan, but its story was ahead of its time. It was published in serialized form beginning in July 1977 in MODERN LITERATURE. The installments were published as a full book in 1983. The male protagonist, Ah Chin, leaves home after his father discovers that he is gay. Then, he finds out about the 228 Peace Park - a secret meeting place for gays. There, they comfort one another psychologically and physically and strive to build a new family identity. The release of CRYSTAL BOYS forced society to look at the marginalized homosexual community and also predicted a brand-new era for gender-focused writings.

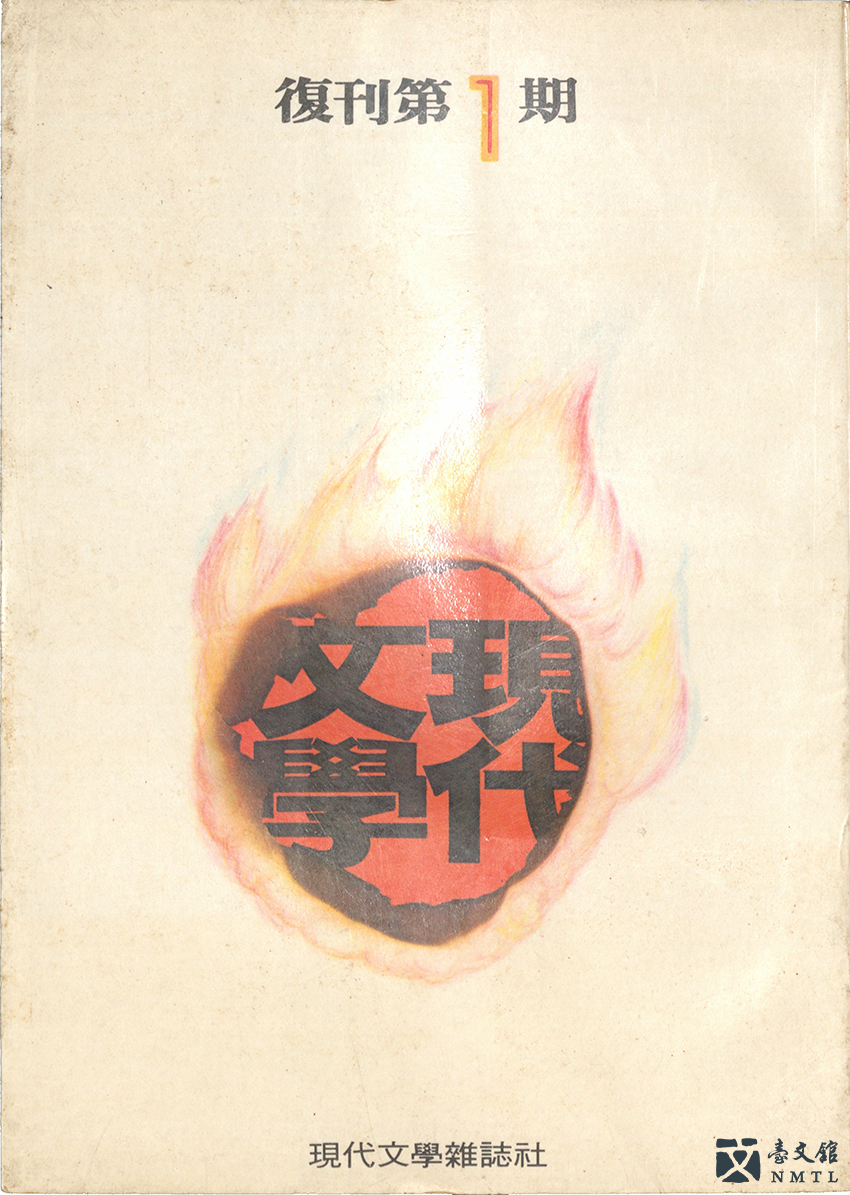

► MODERN LITERATURE BIMONTHLY Issue 1 (Reissued)

The first issue of the reissued MODERN LITERATURE BIMONTHLY was released on July 1st, 1977. The publisher was Pai Hsien-yung. The issue also features his serialized novel "Crystal Boys." The novel was published in installments through the 12th issue. The last part of the novel was published in installments in Singapore's NANYANG SIANG PAU through 1981. The installments were published as a book in 1983 by Vista Read. (Donated by Li Kuei-hsien / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

Factories and Brothels: Women That Were Forgotten

Intellectual and middle-class women were not the only women around. Lu Hsiu-lien's "We Protect Women Hotline" targeted Taiwan's blue-collar female workers, who had made essential contributions to Taiwan's economic transformation. In 1966, Taiwan's first processing export zone was set up in Qianzhen, Kaohsiung. In a very short timeframe, bucolic farm villages were gutted by the new industrial economy and the heady rush of prosperity. Men moved to cities to make a living. And women? They packed up their things and went to work at factories right after finishing their compulsory education. In the meantime, indigenous women from remote areas were lured into prostitution. The hustle and bustle of the city, the mundaneness of life, and feelings of helplessness were all captured in the literature of this time.

When the pimp turns on the lights and starts yelling,

I feel as if I had heard the church bell

toll again on a Sunday morning.

The pure sunlight from North Lala to Nan Dawu

spills over the entire Aluwei Tribe.

When a customer gives a moan of satisfaction,

I feel as if I had heard the school bell

toll again after the whole class saying "Thank you, Teacher" in unison.

The swings and seesaws on the schoolyard

are immediately occupied by our laughter.

When the church bell tolls ──

Mother, do you know?

Hormonal injections have ended your daughter's childhood early.

When the school bell tolls ──

Father, do you know?

The fists of the security guards have smothered your daughter's laughter.

Ring the bell again, Pastor.

Redeem the souls that have lost their virginity.

Ring the bell again, my teacher.

Release the laughter to the schoolyard of freedom.

When the bell tolls again ──

Father, Mother, do you know?

I really, really

wish to be born again…

──Malieyafusi Monaneng, "When The Bell Tolls: For Those Indigenous Child Prostitutes," BEAUTIFUL RICE EARS, 1989.

⁍ Malieyafusi Monaneng, a Paiwan poet. In the 1960s, Taiwan's indigenous communities were impoverished, so there were often human traffickers going to the tribes to abduct young girls and take them to brothels in Taipei as "child prostitutes." Monaneng's sister was one of these girls. This poem describes how the young indigenous girls were forced to work in prostitution, as well as their mindset and reflection.

In the late 1980s, women's organizations, indigenous rights organizations, and churches joined to organize the Huaxi protest, capturing much public attention. The government was subsequently compelled to pass the Child and Youth Sexual Exploitation Prevention Act in 1995, which helped end child trafficking and prostitution.

∞ Guide to Female Power ∞

Thirty-two years ago,

the groom held thorns in both of his hands (perhaps he did not know)

as a bouquet of flowers for me.

The bride was thankful and became a tree.

Flowers are a lock of love;

thorns are chains of misery.

I kneeled and bowed to the roster of the dead in the future,

forgetting my parents' sacrifice for me.

My blood, sweat, and tears are my duties,

as I strive to stay loyal to my family.

I mold flowers of an obedient daughter-in-law;

I mold flowers of a wife;

I mold flowers of a mother;

I place them on the tips of the thorns,

and put on a smile of "happiness and prosperity"

that covers up the pain of being punctured,

trying not to let others know.

When my heart is left with endless punctures,

the tree that cannot shout twists its branches.

Dear God, let the strong wind blow.

Please open my lock of thorns;

let me mold again

a flower of beautiful loneliness

to heal my wound.

Please just open my lock of thorns!

──Chen Hsiu-hsi "Lock of Thorns", 1975.

Forever Auntie: Chen Hsiu-hsi

Chen Hsiu-hsi, born in 1921, started to write haiku and tanka poetry in her teenage years. She wrote more than 3,000 poems throughout her life. After the war, she began to learn Chinese and wrote her first contemporary poem in Chinese at the age of 50. In 1971, she served as Director of Li Poetry Society. She was a generous person and dedicated herself to grooming later generations of poets. The literary world nicknamed her Auntie Chen. Her most famous work was "Taiwan" which was then adapted to the political song "Formosa (The Beautiful Island)" by Lee Shuang-Tze. She had a rough marriage and fell into despair after being cheated on by her husband. "Lock of Thorns" depicts her bitterness owing to being trapped in her marriage.

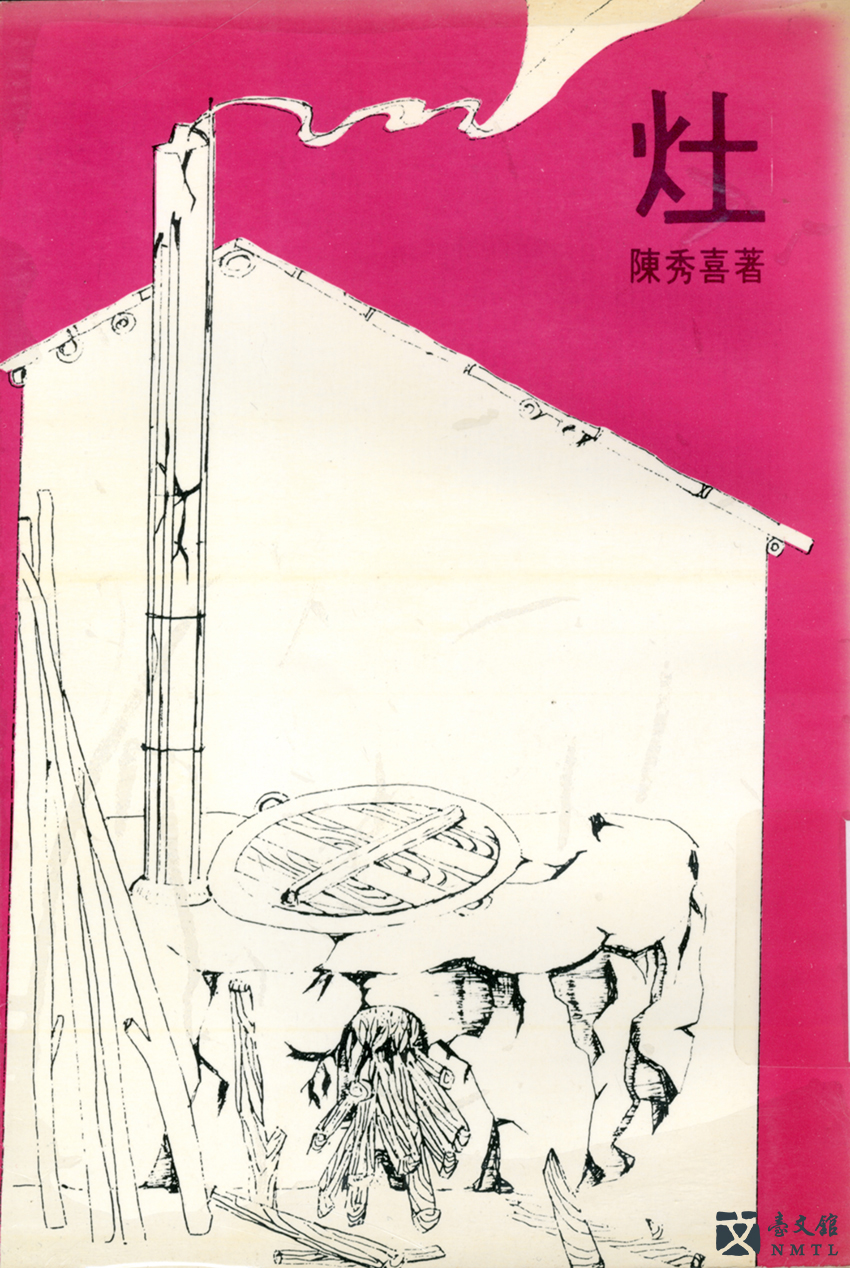

► Chen Hsiu-hsi's Poetry Collection: STOVE

First printing from December 1981 by Chunhui. Due to the poet's marital and life experiences, her poems are mostly about maternity and female awareness against the suppression of traditions. "Thorns and Thistles" and "Stove" address the shackles put on women by traditional marriage and the physical and psychological pains women suffer from conceiving and giving birth. (Donated by Li Kuei-hsien / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

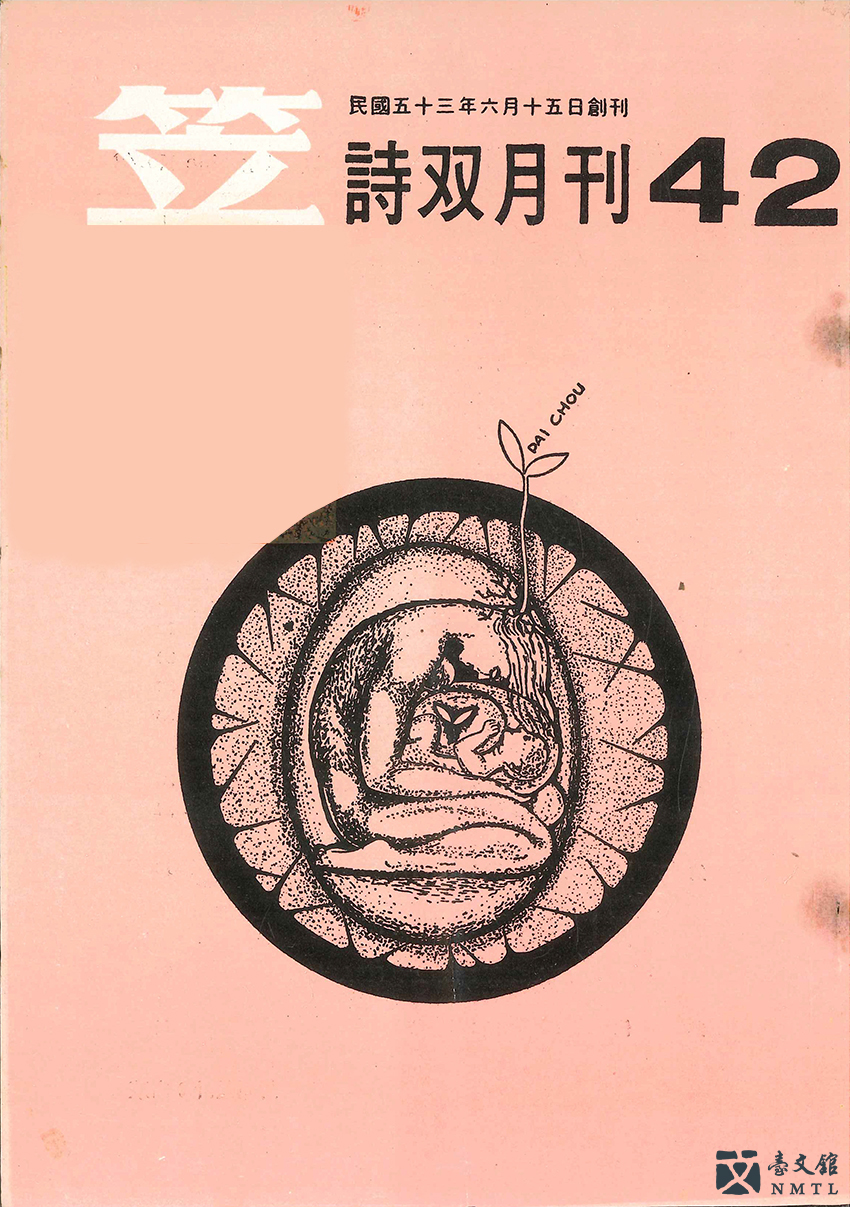

► LI POETRY MAGAZINE, Issue 42

Published in 1971. The cover is the work of poet Bai Di. Starting from this issue, the director's name, Chen Hsiu-hsi, appeared on every copyright page until she passed away in February 1991. During this time, Chen moved to Guan Zi Ling and named her house Li Yuan. She also actively engaged in grooming the next generation of writers. After she passed away, her family set up Chen Hsiu-hsi Poetry Scholarship. Starting in 1992, the scholarship was awarded every Mother's Day for 10 years until 2001. It was given to poets such as Du Pan Fang-ge, Li Yu-fang, Chiang Wen-yu, Zhang Fang-ci, Chaing Zi-de, and Zhan Che. (Donated by Wu Yong Fu Foundation / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

◇ ◇ ◇

Gardener of The Soul: Lady Wei Wei

Lady Weiwei's real name was Le Chenjun. She once acted as Director of Mandarin Daily News. She also wrote for the "Lady Wei Wei Column" in UNITED DAILY NEWS for 26 years. The "Lady Wei Wei Column" family version invited female readers to share their secrets and worries. In an era when psychiatry and psychotherapy were still immature, Lady Wei Wei was a channel for Taiwanese women to speak about their life stories. Due to her reputation for balancing work and family, Lady Wei Wei was a role model for women at the time.

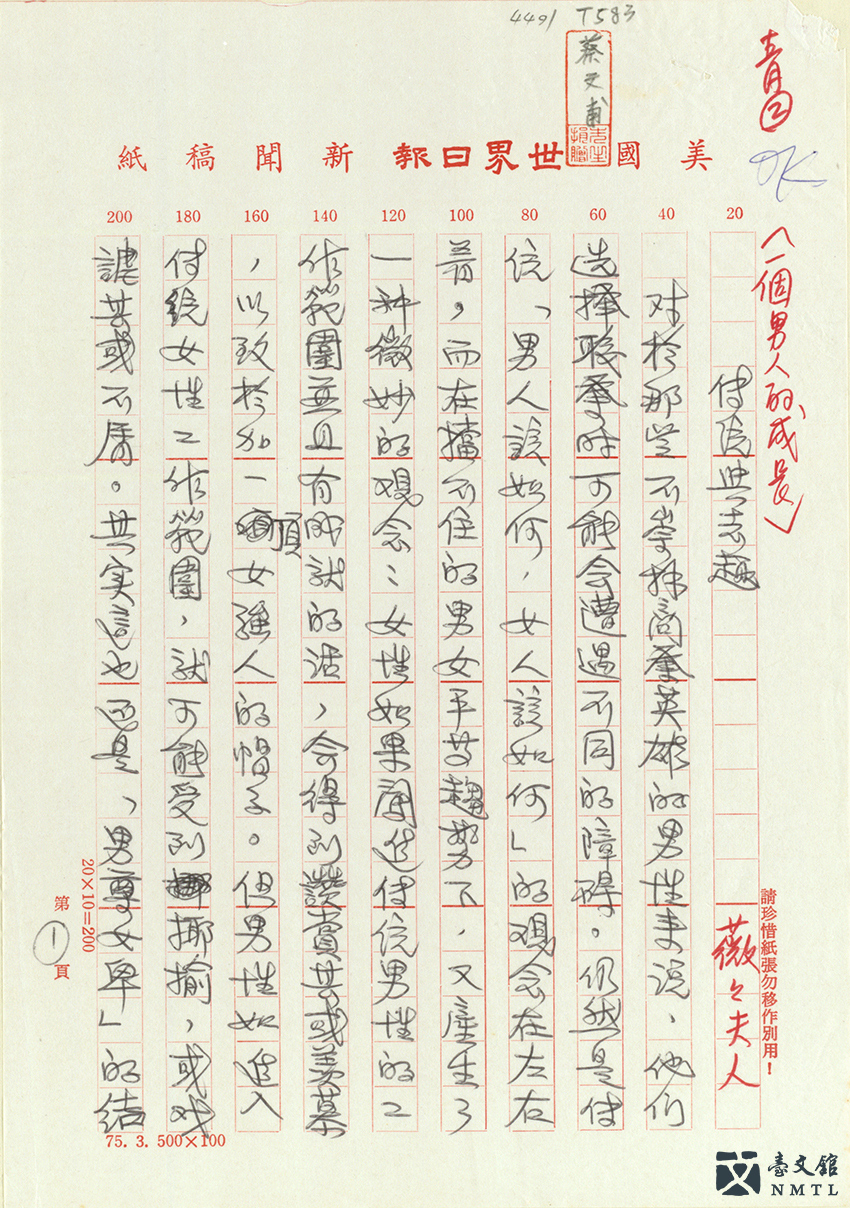

► Manuscript of "Traditions and Hobbies"

This article was included in Madam Vivi's A MAN'S GROWTH. She believes that, regardless of gender, everyone should be able to give full scope to their talent and pursue their goals rather than be shackled by gender stereotypes. (Donated by Cai Wen-fu from Chiuko Publishing House / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

◇ ◇ ◇

A Free Spirit: Sanmao

Sanmao, aka Chen Maoping, was unable to adapt to middle school education. So, she left school to be homeschooled and began to write. She later on studied philosophy at the Chinese Culture University. When she was 24, she went to study in Spain, where she met Jose. They went to the Sahara Desert together, got married, and settled down. She then wrote works that were bestselling books for the next decades, including STORIES OF THE SAHARA and WEEPING CAMEL. She became a symbol of a nomadic woman in search of her own identity. Sanmao was also the translator of the comic stirp MAFALDA and the lyricist of many folk songs such as "Olive Tree." Her poignant love story and far-flung travels have influenced generations of readers in Taiwan and China.

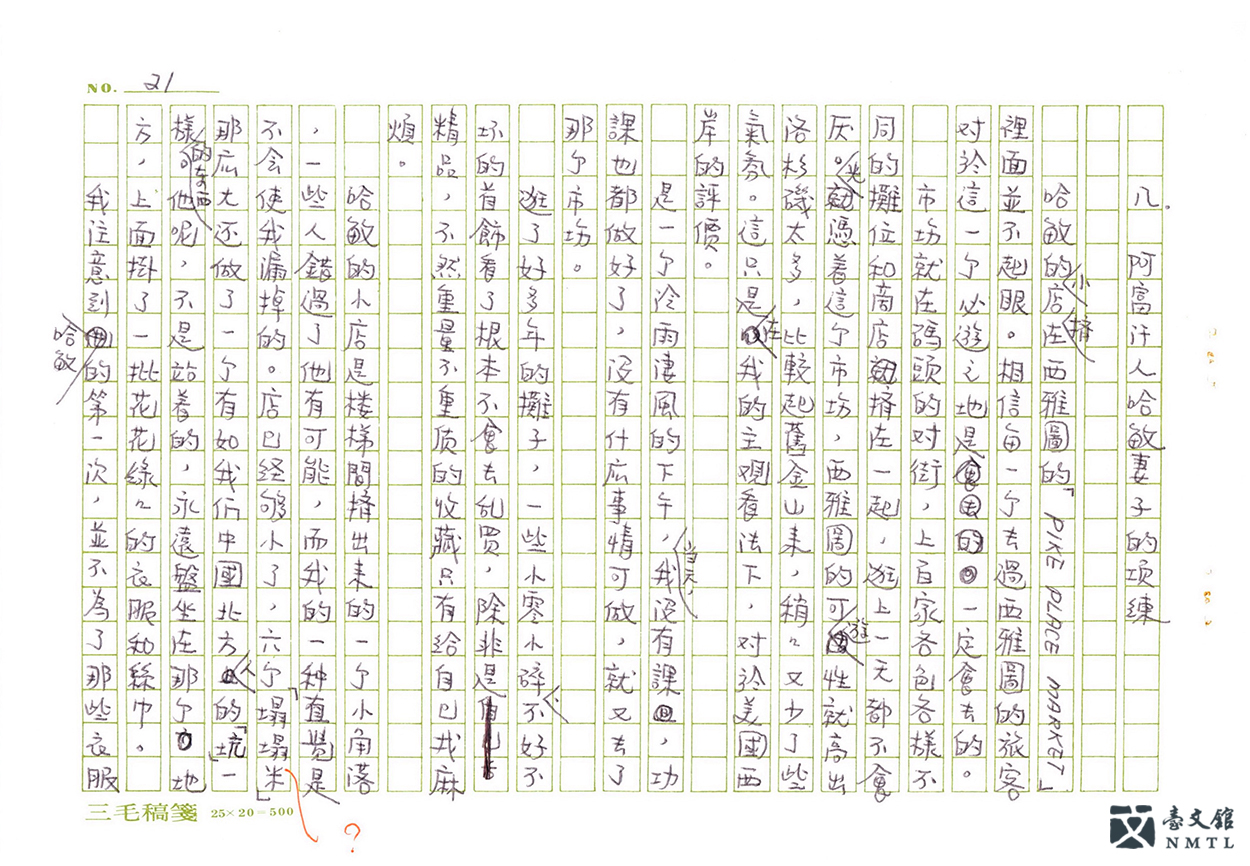

► Manuscript of "Necklace Belonging to Afghan Hamin's Wife"

One of the narratives featured in Sanmao's MY BABY. It depicts how Sanmao befriended an Afghan secondhand dealer, Hamin, in Seattle and bought a necklace that had belonged to his wife. The work is featured in MY BABY. (Donated by Chen Tian-xin, Chen Sheng, Chen Jie / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

► Necklace Belonging to Afghan Hamin's Wife

One of Sanmao's collections. Before Sanmao left Seattle, she said goodbye to Afghan secondhand dealer, Hamin, whom she often went to. She bought this necklace, which belonged to Hamin's wife, about whom he often talked. Related stories can be found in MY BABY. (Donated by Chen Tian-xin, Chen Sheng, Chen Jie / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

► Still Locked (inscribed with characters "Live to Be A Hundred")

There are many items representing traditional Chinese culture in Sanmao's collection, including this lock necklace inscribed with characters "Live to Be A Hundred." It was a present from Jin Yong's wife. Related stories are featured in Sanmao's MY BABY. (Donated by Chen Tian-xin, Chen Sheng, Chen Jie / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

► Plates of Happiness - Colorful Porcelain Plate

One of Sanmao's collections. This was the first porcelain plate she bought in Andalusia, Spain, where her husband Jose was born. Four years into their marriage, they finally saved enough money to buy a house with a garden. Sanmao also learned to decorate the house with porcelain plates on the walls, which also symbolized her new beginning with her husband. Related stories can be found in MY BABY. (Donated by Chen Tian-xin, Chen Sheng, Chen Jie / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)

► Leather water bottle

When Sanmao was travelling abroad, she collected items to commemorate her encounters with people in different times and places. This leather water bottle is one of these. It is a bit similar to the wineskin Sanmao mentioned in "My Baby," which was also used during travel. Her many readers followed Sanmao to different places across the world through her adventures and the stories hidden in her collected items. (Donated by Chen Tian-xin, Chen Sheng, Chen Jie / From the National Museum of Taiwan Literature permanent collection)