The Spirit of Wildlife in Taiwan Literature

Sky

Taiwan is our main habitat during the winter. Every October to March, about a thousand of us gather around the wetlands and fish farms in Chiayi, Tainan, and Kaohsiung to wait out the winter.

Each year, we are treated like celebrities and attract large crowds, among which are many photographers, who take pictures of us as if we're models.

People also call us "black-faced dancers" because we glide gracefully across the sky.

(Provided by Taiwan Black-Faced Spoonbill Conservation Association)

The black-faced spoonbills arrive in my hometown starting from late September through October. For bird lovers, the first ones to see these birds earn year-long bragging rights. Sometimes they even bicker and fight about who was truly the first to spot a black-faced spoonbill. Uncle Jian Yong was the most aggressive of this group. He was often the first one there, maintaining a vigil and keeping a watchful eye. I'd join him sometimes if I had nothing else to do.

——

The black-faced spoonbills use their long bills rather than their eyes to search for food, stirring the water to find fish. Some people use the Taiwanese word lā to describe this action. The same word is used in the Taiwanese phrase lā thng, which means “to stir the soup around,” and lā-sái, meaning “to talk about random things.” The birds race the wind and paint ripples on the water.

——Hung Ming-tao, "Waiting for the Black-Faced Spoonbills," The Road to Come

In this book Hung discusses how the local people reacted when they realized that their beloved wetland was to be destroyed and replaced by a road. ”Waiting for the Black-Faced Spoonbills” is set in a coastal area of southwestern Taiwan. The protagonist is a student studying black-faced spoonbills. Through his eyes, we see the clash between local development and environmental conservation. Like nature, the voices of defenseless contenders are destined to be silenced under the merciless reign of local political forces.

📖 Hung Ming-tao, The Road to Come, Chiuko Publishing

The nine short stories in this book are set in the countryside around Tainan and Gangshan. Hung narrates the everyday lives of people using both Taiwanese and Mandarin Chinese.

🎬 "Little Egrets" by Anarchy In Taiwan (Provided by: Liu Pei-lun)

For the sake of development, how many cries were uttered by the animals of this land? “Bai Lu Si” (Little Egrets), a fusion of criticism and deep emotion, sings of the helplessness of homeless little egrets.

"Little Egrets" by Anarchy in Taiwan

Lyrics:

In this bustling city,

People care only about money.

No laws or rules or acts of mercy—

only wealth makes a man happy.

In this distorted society,

people are nothing.

Land is destroyed to build karaokes

and nature goes neglected, cold- heartedly.

I saw little egrets sobbing

in the gutter at the end of the alley.

They said to me,

"The forest our parents lived in

are now lifeless buildings.

Oh, who is still willing, ...

willing to listen, to see our sufferings?

Please, we ask for nothing, ...

nothing more

than a piece of land to live on."

Government officials won't stop drinking,

businessmen thrive on brown-nosing.

How do you look at yourselves in the mirror every morning

and not see the pain you're causing?

I feel sorry, ... sorry for your parents and siblings

and for this land that needs healing.

Please, have mercy

and stop what you're doing.

I want nothing, ...

nothing more than, once again,

to see little egrets flying.

I saw little egrets sobbing

in the gutter at the end of the alley.

They said to me,

"The forest our parents lived in

are now lifeless buildings.

Oh, who is still willing, ...

willing to listen, to see our sufferings?

Please, we ask for nothing, ...

nothing more

than a piece of land to live on."

Little egrets fly

above golden fields.

Little egrets perch

upon our rooftops.

Oh, little egrets fly freely

over this beautiful island.

Little egrets fly

through winter and spring.

Oh, little egrets fly freely

over this beautiful island.

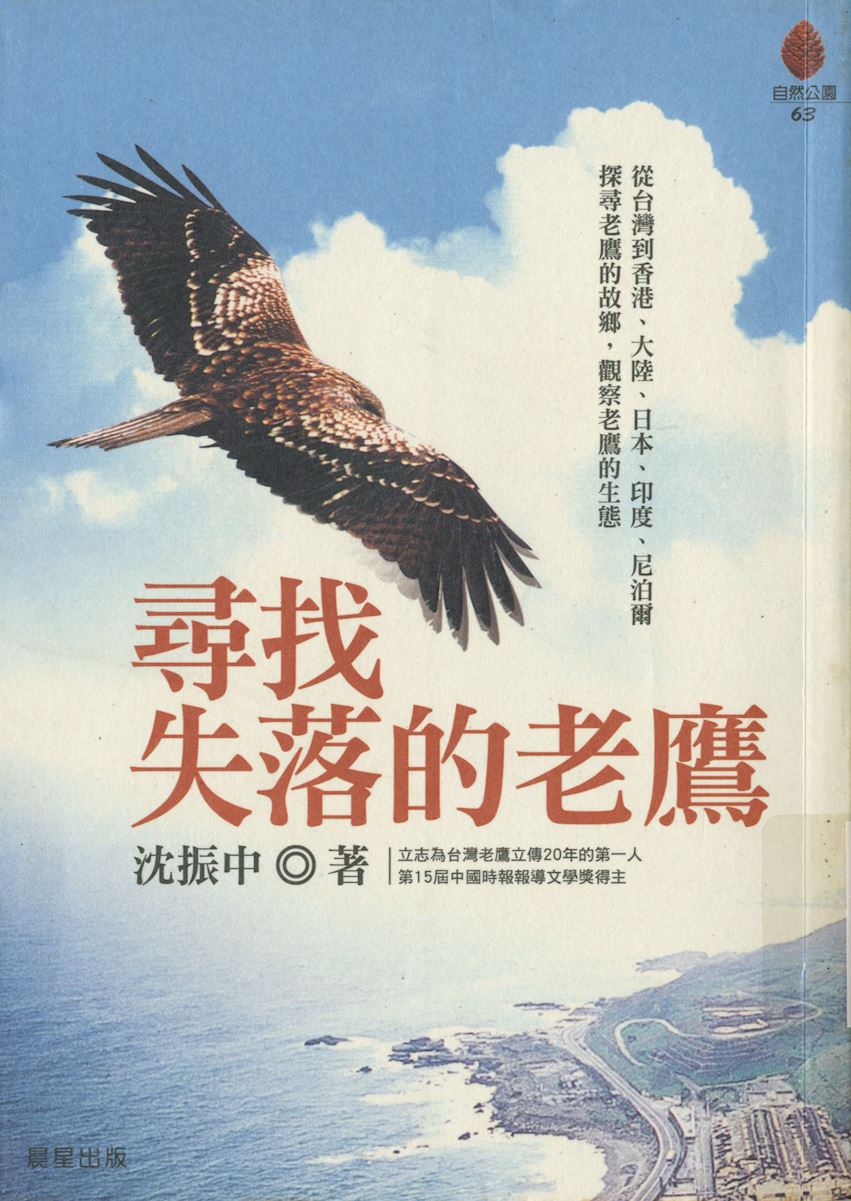

Taiwanese people used to call all big birds like us "eagles," but our proper name is "black kite." Even as recently as a half century ago, we were a frequent sight in Taiwan's rural villages, feasting on carrion or capturing chicks that had wandered too far from safety. Back then, chickens were raised free range, so their chicks were easy targets. This was actually where the game "Eagle-chick chase" originated from. We had adapted to live with humans, and even learned to build our nests with twigs and pieces of white-colored garbage such as plastic bags, underwear, and wrapping paper.

However, during the 1980s, people in rural areas started using rat poison and pesticides. Many of us died after eating poisoned rats or smaller birds. As a result, our numbers dropped drastically. Thankfully, in recent years the use of these chemicals has decreased and our population has grown from 302 in 2007 to 583 in 2018.

.jpg)

(Provided by Tsai Taihua)

To these eagles, chicks mean no more empty stomachs, but the garbage dumps mean so much more. They not only find food there but also entertainment, playing with plastic bags, clothes, paper, aluminum foil, underwear, and gloves. The eagles toss these around and chase each other around for them. The eagles also use the opportunity to hone their flying skills and establish bonds with one another. During breeding season, the fruit of mankind's throwaway culture is also put to good use as building material for nests. Eagles set shredded garbage in the middle of their nests as a cushion.

——Shen Chen-chung, "Eagles Dining on Eels and Grilled Meat," In Search of the Lost Eagles

This is Shen Chen-chung's third book dedicated to eagles, written after years of rigorous observation and documentation. In this book, he writes about eagles in Taiwan, as well as those he saw during trips to Japan, Hong Kong, and Nepal with photographer Liang Jie-de. Their work helps us all envision the future of Taiwan's eagles.

📖 Shen Chen-chung, In Search of the Lost Eagles, Morningstar Publishing Co.

Shen Chen-Chung, known as "Mr. Eagle," surveyed and studied the ecology of black kites from 1992 to 2012.

In the 1950s, people treated us like flying banknotes–"this butterfly is worth three dollars, that one is worth five, and this adult one —— ten dollars". We were captured and shipped by the millions to be mounted in displays and butterly-wing mosaics.

Our habitat was gradually turned into commercial orchards and betel nut plantations in the 1970s, placing the survival of many of our kind at peril as our numbers drastically declined.

But thanks to growing attention toward environmental conservation, we're no longer being used in art displays. We now instead fly free in our familiar surroundings and coexist with humans.

(Souce: Wu Ming-yi, The Dao of Butterflies)

As I turned around, I discovered another vibrant butterfly perched atop a goatweed plant. Based on its color patterns, it may have been a delias. The elevation of Danayi Valley isn't that high, so the chances of it being a Delias lativitta formosana or Delias berinda wilemani were quite low. These butterflies, although similar in appearance, have different feeding habits both as caterpillars and as adults. Being able to observe them in this way is a means for us to learn just a little bit more about them. Delias will not dine on any plant that is not in the caper family and no Delias berinda wilemani can bear the heat of this valley.

It's similar to how Yangui and Shu-hui told me that they could never get used to life in Taipei and its "really narrow" city streets. The city made them feel extremely restless ... So much so that they returned to their hometown to work at a church. We have neither the right nor power to demand that butterflies like Delias berinda wilemani eat Taxillus lonicerifolius lonicerifolius plants. Similarly, we have neither the right nor power to demand that the Tsou acclimate to city living or adopt "a more civilized lifestyle."

——Wu Ming-yi, "Danayi Valley," The Dao of Butterflies

The author strikes in this book a balance between documenting real-life events and expressing his deep-set emotions. His words convey details that touch on the history of nature, art, and literature and that entwine intimately with feelings and memories, creating a tender soliloquy. This book is thus a forest of words, making it incomparable to any other text. Within this forest, butterflies are lantern-carrying guides that illuminate the darkness and lead the author to better understand the life that flows around him.

📖 Wu Ming-yi, The Dao of Butterflies, Eryu Culture Publishing House

Complementing his previous work "The Book of Lost Butterflies", this is Wu Ming-yi's second essay collection to focus on butterflies.