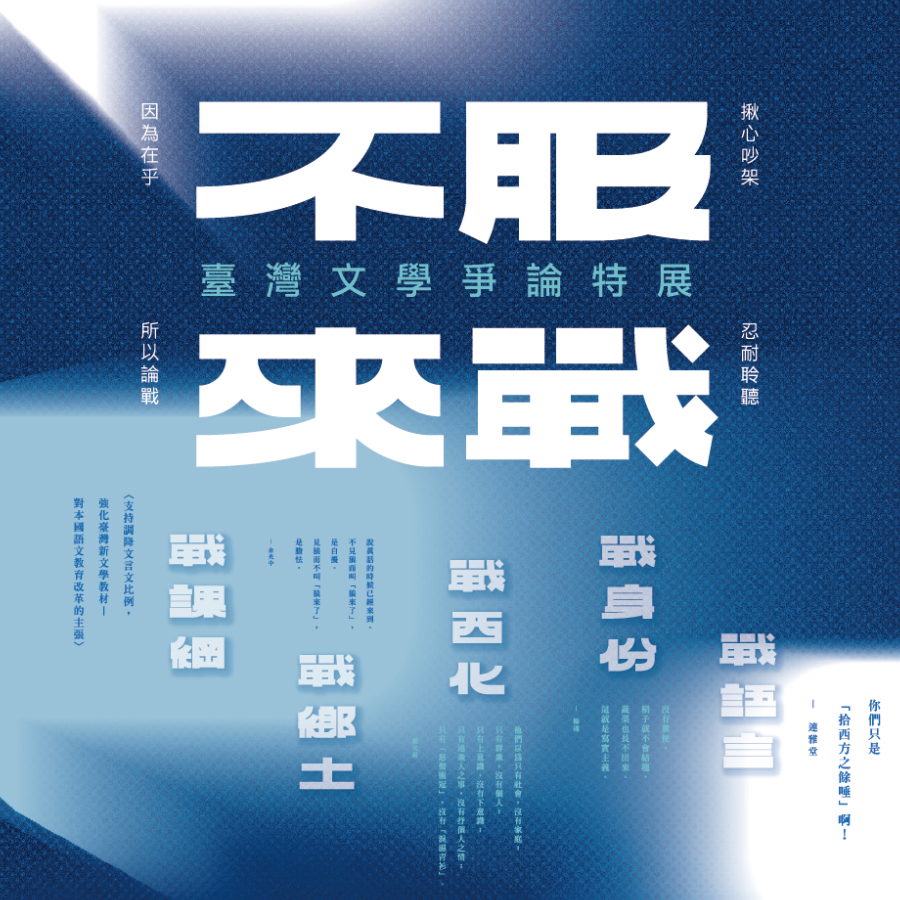

Taiwanese Literature's "Conundrum about Identity"

From the end of the Japanese rule period to the beginning of the Nationalist government, and from the suppression during the colonial period to the gaps between immigrant backgrounds, Taiwanese writers began to face the most basic problems: When we write, who are "we"?

【The Main Argument】

In 1937, after the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out, Taiwan entered the war period as the Japanese colonial government began a cultural Japanization and southward industrial expansion. In the meantime, Japan was desperate to build a "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere." Therefore, in the 1940s, the "Greater East Asia Literature Meeting" and "Wartime Literature Meeting" were successively held, which gathered Taiwanese, Japanese, and Korean writers to discuss how literature could be used to show loyalty to Japan.

This was an example of politics forcefully intervening and controlling the development of literature under a totalitarian regime. Writers either obeyed or resisted. Thus, the debate over "fecal realism" broke out. Immediately after the war, Taiwan was taken over by the Nationalist government, and the literature written during the "Japanization period" was questioned by mainland writers who were not familiar with the struggles of Taiwanese writers. In "the Supplement Qiao Debate," these mainland writers strongly criticized Taiwan for not having its own literature and uniqueness. Within only a few years, Taiwanese literature was faced with an identity dilemma by not being "Japanese enough" and "not being Chinese enough." What should Taiwanese writers do?

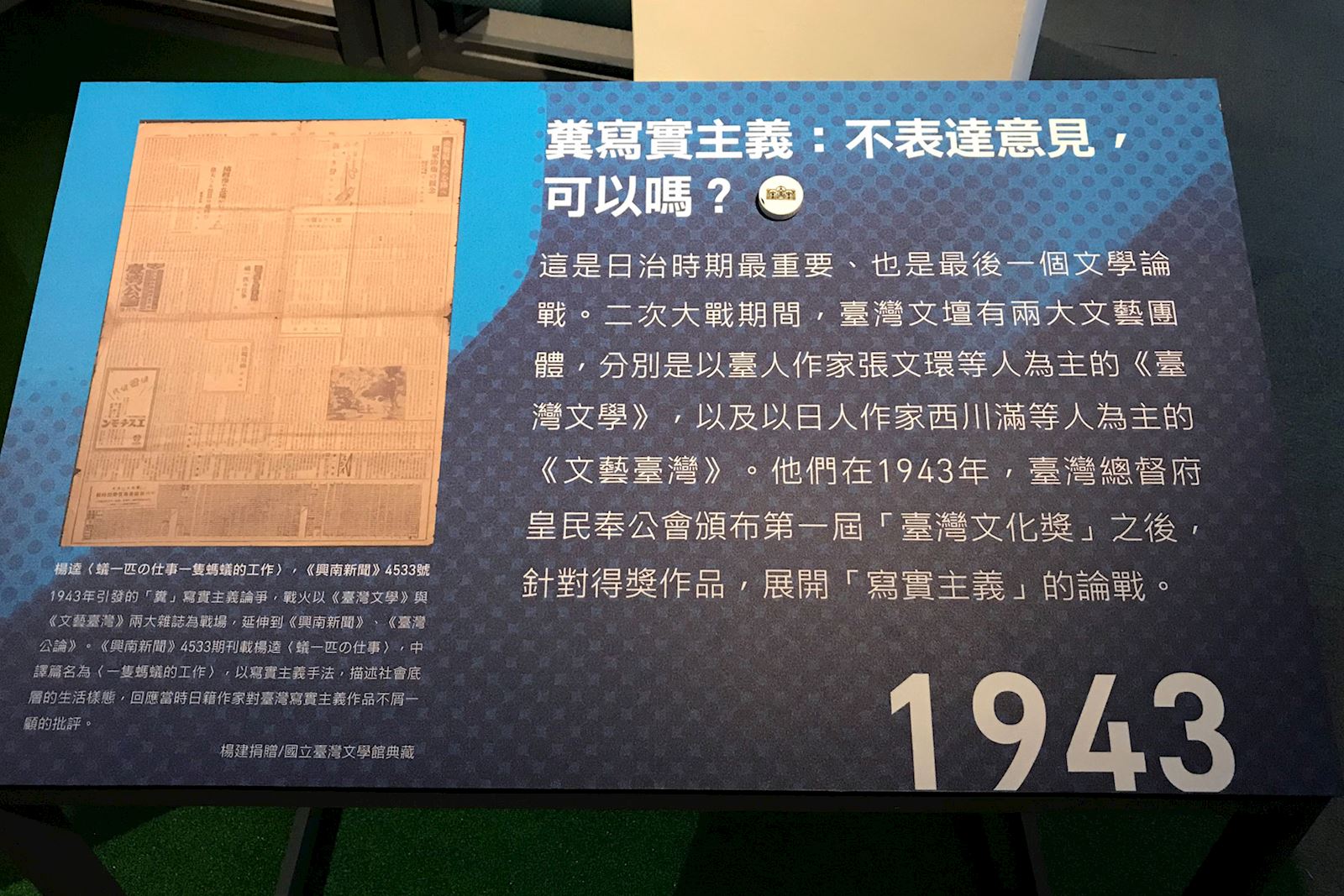

◎ 1943 Fecal Realism: Is it acceptable not to express any opinion?

This was the most important and the last literary debate during WWII. During the war, there were two major literary organizations: One was TAIWANESE LITERATURE, led by Taiwanese writers such as Wen-Huan Zhang, and the other was LITERARY TAIWAN, led by Japanese writers such as Mitsuru Nishikawa. After the first Taiwan Culture Award by the Japanization Assistance Association, Governor-General of Taiwan, in 1943, they began the debate over realism based on the winning pieces.

.png) Mitsuru Nishikawa: The "fecal realism" in Taiwanese literature is vulgar and unseemly. There is not a single trace of Japanese traditions. The real realism is nothing like that!

Mitsuru Nishikawa: The "fecal realism" in Taiwanese literature is vulgar and unseemly. There is not a single trace of Japanese traditions. The real realism is nothing like that! In 1943, WWII was still ongoing. As the war heated up, the Japanese colonial government began imposing restrictions on literary creation and promoted "imperial literature," requiring Taiwanese writers to write in accordance with the government policy.

Under this rigorous policy, Taiwanese writers, led by Wen-Huan Zhang, were unable to fight back openly. Therefore, they rebelled using naturalism. The so-called "naturalism" was a literary trend introduced from Europe and the U.S. Acting as a variant of "realism," naturalism proposes that writers should depict people and things objectively without too many subjective opinions. Since no subjective opinions were involved, the writers were able to avoid clarifying "whether they supported the war or not."

However, Mitsuru Nishikawa, the pro-Japan Taiwan-born Japanese writer, published "A Review on Contemporary Literature" in the middle of the year. This article criticized Taiwanese writers' works as "fecal realism," meaning that Taiwanese writers only wrote about reality that was as ugly as "feces," which was not realism at all.

At the same time, he also criticized Taiwanese writers' naturalist writing for its poor imitation of the West and lack of any characteristic of Japanese literature. At the time, Japan was in a war against the U.S. Thus, this criticism also implied "Taiwanese writers were not loyal to their country while passively opposing the war."

This article hurls insults at Taiwanese writers with vulgar words and carries political implications. Its publication caused a commotion in the literary scene. Except for Hayao Hamada and Shih-Tao Yeh, student of Mitsuru Nishikawa, almost the entire literary scene lashed out at Nishikawa.

Kui Yang: Rice grains will not ripen without feces. Vegetables will not grow either. This is realism.

Kui Yang: Rice grains will not ripen without feces. Vegetables will not grow either. This is realism.Among all the representative articles against Mitsuru Nishikawa, Kui Yang's "Advocacy of Fecal Realism" was the most important piece. At the time, most Taiwanese writers criticized that Nishikawa attacked people with feces. Kui Yang used an alternative approach and wrote that "feces are good! Land needs feces as fertilizer and literature comes from land."

Yang's counterattack not only clarified his own stance, but also implied that Nishikawa's views were narrow-minded and that, furthermore, Nishikawa's "Japanese literary tradition" was only the kind of literature that was romantic, empty, and unrealistic. Yang deliberately brought up works from two Japanese writers: Reiko Sakaguchi and Tetsuomi Tateishi, which cleverly avoided political censorship and showed that he was not encouraging any conflict between Japan and Taiwan.

However, even though "Advocacy of Fecal Realism" was better in its reasoning, it still did not survive political suppression. At the end of 1943, in Taiwan's Decisive Battle Literature Conference, Mitsuru Nishikawa published "The Battle Position of Literary Magazines," including all the literary magazines into his LITERARY TAIWAN in a bid to eradicate platforms for submissions by Taiwanese writers.

At this point, the once prosperous Taiwanese New Literature was severely sabotaged until the war ended.

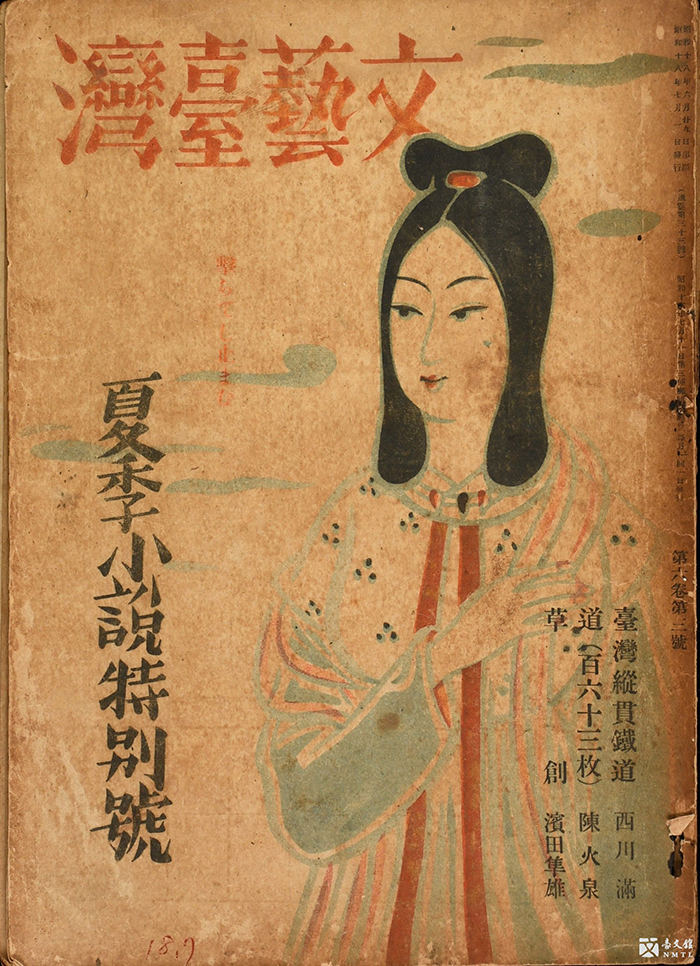

LITERARY TAIWAN No. 1 & No. 3, Vol. 6

Supervised by Mitsuru Nishikawa, Literary Taiwan was the longest lasting literary magazine with mixed themes during the Japanese period. With an ultimate goal of promoting art, the magazine featured literature, folk culture, and paintings. The first issue was released in 1940. In the beginning, it was published by Taiwan Writers Association. The publisher changed to the Literary Taiwan Society in March 1941. During the war, the guidelines of the magazine echoed the national policy of Japan and continued until its suspension in 1944. Nishikawa submitted "Literary Criticism" in No. 1 of Vol. 6 to criticize the nativist literature of Taiwanese writers as "fecal literary realism."(Donated by De-Shi Huang and Tian-Yi Zhao, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

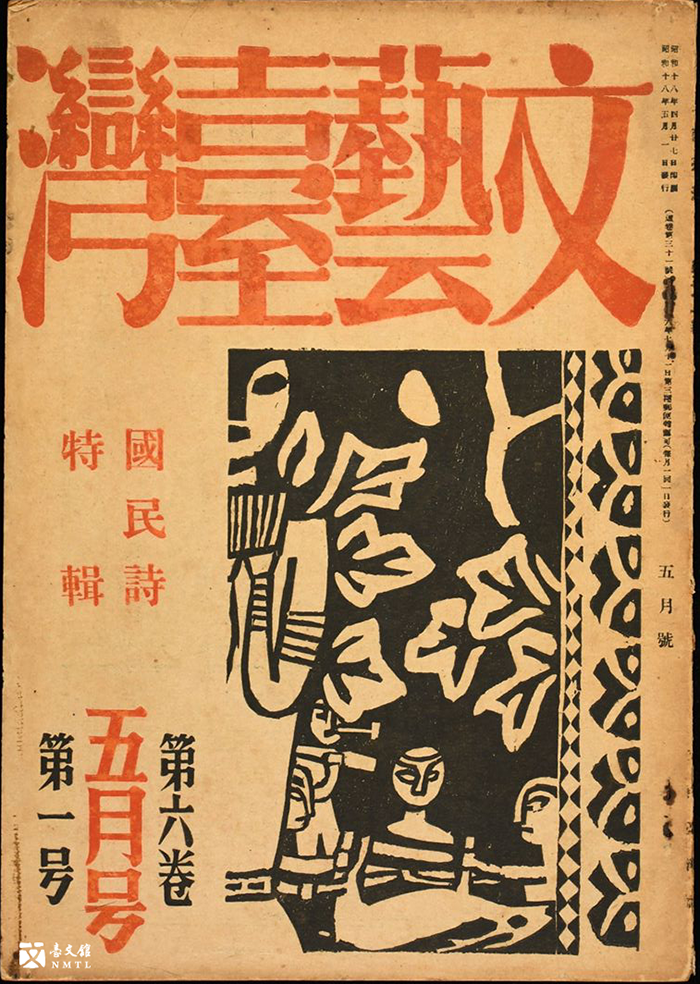

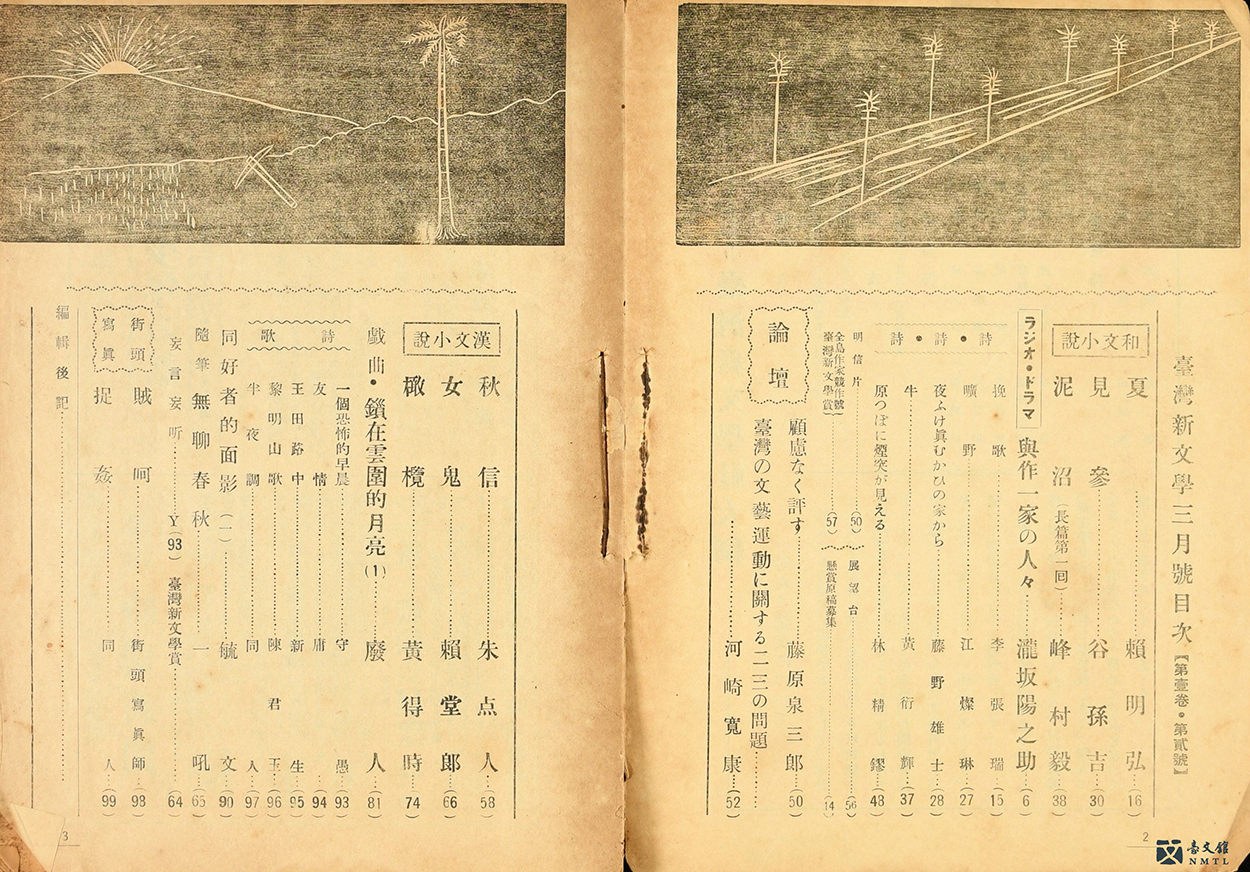

NEW TAIWANESE LITERATURE No. 2 & No. 6, Vol. 1

Founded in 1936, while withdrawing from Taiwan Literature Alliance and starting somewhere else, this magazine maintained its aim of unifying Taiwanese writers. At the same time, it associated with left-wing writers from Japan, which could be seen from the submissions that came from Fujino Yuji and Yasuo Tanaka in No. 2 & 6 of volume 1. In No. 2, Fang-Nian Lin's "See the Chimney from The Vast Field" has a strong realist style and resembles a Japanese free-verse poem. Meanwhile, the No. 6 issue features works from Shui-Tan Guo, Xin-Rong Wu, and Feng Zhu. It was evident that after Kui Yang entrusted Shui-Tan Guo with coordinating the magazine, the number of submissions from writers from the coastal areas and southern Taiwan increased. Their works are filled with realism.(Donated by Tian-Yi Zhao, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

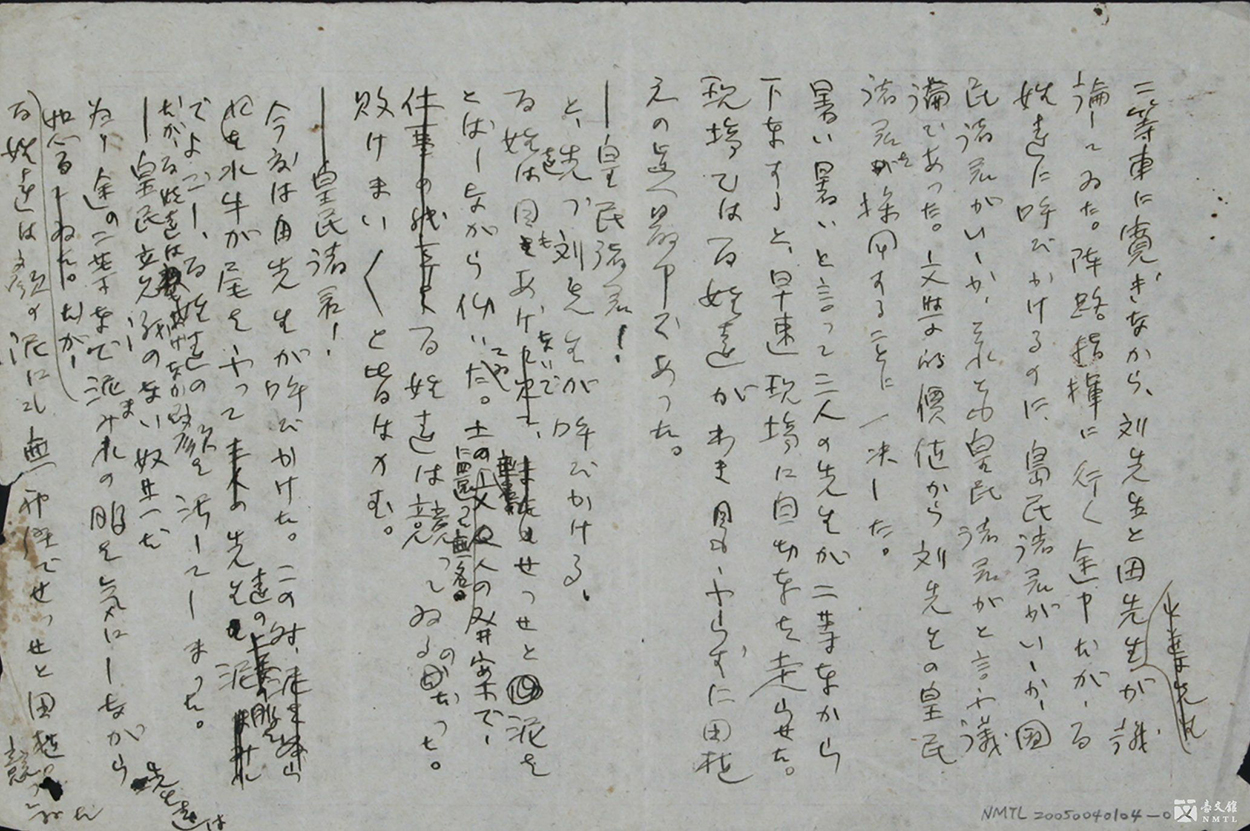

Kui Yang, "Rice Transplanting Competition"

A manuscript in Japanese. The translation of the title is "Rice Transplanting Competition." In this fable, Kui Yang responded to the controversy over fecal realism in 1943. In the story, "Mr. Liu" and "Mr. Tien" teach farmers how to transplant rice seedlings for competition; after they are splashed with cow dung on the field, they respond with disgust. On the surface, they led the Japanization movement, yet they lacked the knowledge that cow dung and mud are the indispensable sources of nutrients for rice seedlings, insinuating that Mitsuru Nishikawa and Hayao Hamada did not understand what Taiwanese society was really like. (Donated by Jian Yang, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

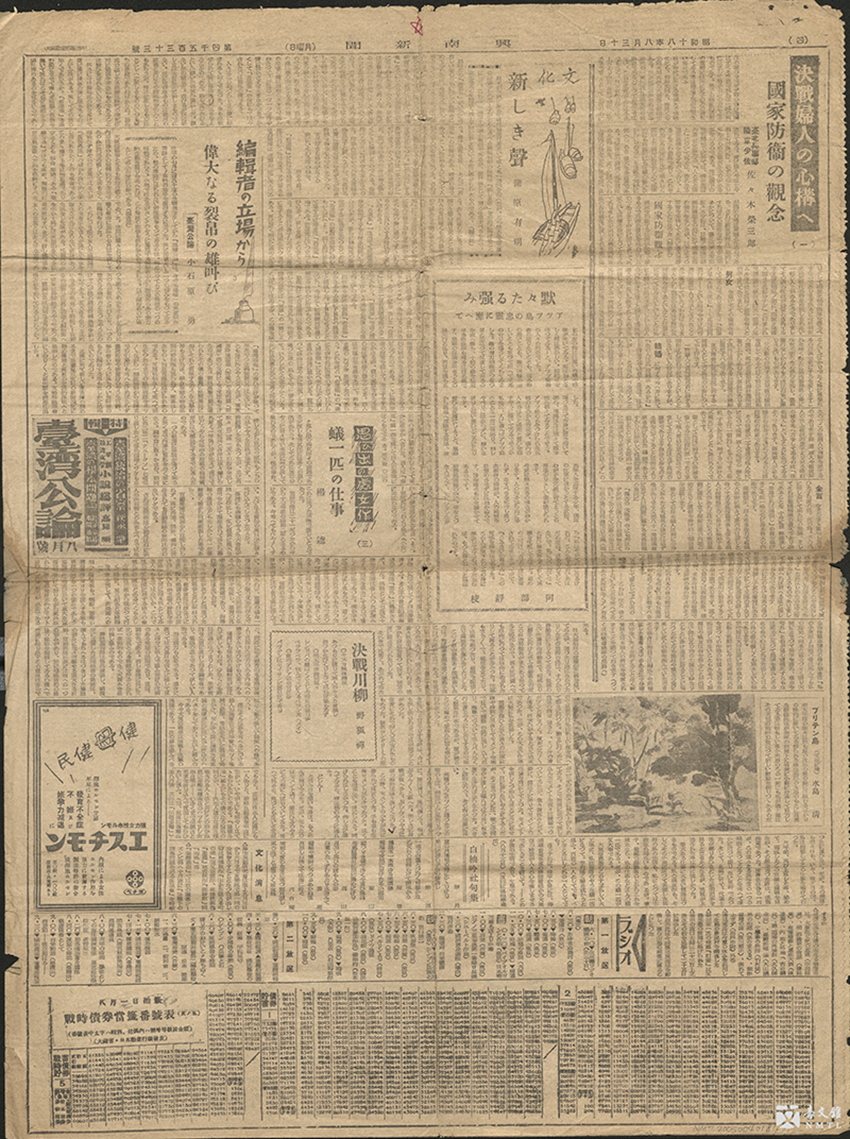

Kui Yang, "The Work of An Ant" in XINNAN NEWS No. 4533

The "fecal realism" debate in 1943 took place in two major magazines: TAIWANESE LITERATURE and LITERARY TAIWAN. Then it extended to XINNAN NEWS and TAIWAN PUBLIC OPINION. Issue 4533 of XINNAN NEWS published Kui Yang's "The Work of An Ant." Written with a realist style, the work illustrates the lives of people from the bottom rung of the social ladder to respond to the harsh criticism of the realist literature in Taiwan by Japanese writers. (Donated by Jian Yang and Xin-Yi Su, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

◎ 1947-1949 Supplement Qiao Debate: Writers must work together, but do they recognize their differences?

Following the end of WWII, Japan surrendered and Taiwan was taken over by the Nationalist government. Within two years, Taiwanese underwent the excitement of being free from colonization followed by complete disillusionment with the Nationalist government. Finally, the February 28 Incident erupted. Six months after the incident, mainland writer Lei Ge founded "Supplement Qiao," trying to communicate with both mainland and Taiwanese local writers in order to discuss the future of Taiwanese literature. The foreword in the first issue mentions that "Qiao (bridge) symbolizes the transition from old to new; Qiao symbolizes the transition from unfamiliarity to friendship; Qiao symbolizes a new world; Qiao symbolizes an emerging new era." Using "Supplement Qiao" as a platform, writers discussed if "Taiwanese literature" really had its own uniqueness based on the atmosphere in Taiwan at the time; they also discussed the relationship between Taiwanese literature and Chinese literature. This series of arguments was later called "The Supplement Qiao Debate."

.png) Kui Yang: Taiwan's literary scene does not cry nor scream; it is deadly quiet. Why are we silently waiting for death?

Kui Yang: Taiwan's literary scene does not cry nor scream; it is deadly quiet. Why are we silently waiting for death? After the initial commotion shortly after the war and the severe damages brought by the February 28 Incident, writers realized that it was essential to solve the conflict between people from different immigrant backgrounds and contemplate on the future of literature.

In 1947, Lei Ge founded Supplement "Qiao" for TAIWAN XINSHENG BAO, Taiwan's biggest newspaper. The concept of "Qiao" was building a communication channel for writers from different immigrant backgrounds to create a future for Taiwanese literature. Lei Ge, as a writer from the mainland, worked hard to collaborate with severely damaged local Taiwanese writers through translation and symposiums.

In such context, Supplement "Qiao" initiated the discussion on "the future of Taiwanese literature." Ming Ouyang, Feng Yang, and Kui Yang began to publish articles, which became a dozen rounds of debate.

This "Supplement Qiao Debate" initiated several major debating topics in Taiwan after the war: is "Taiwanese literature" an appropriate name? What's the relation between "Taiwanese literature" and "Chinese literature"? How should Taiwanese literature during the Japanese rule period be viewed?

These discussions eventually ended up with one focus: Did Taiwanese literature have its "unique characteristics"?

Tuo-Ying Luo: Taiwanese literature's characteristics are regressive, such as being "low-spirited, melancholic, numb, and enslaved;" "nativist literature" is mostly "literature" with little worth and dissociated from the revolution in China.

Tuo-Ying Luo: Taiwanese literature's characteristics are regressive, such as being "low-spirited, melancholic, numb, and enslaved;" "nativist literature" is mostly "literature" with little worth and dissociated from the revolution in China. During the "Supplement Qiao Debate," writers generally agreed that literature should focus on the left-wing, people-oriented literary realism. However, despite this consensus, writers had different views regarding "whether Taiwanese literature had its own unique characteristics."

Mainland writers such as Tuo-Ying Luo and Ge-Chuan Qian mostly did not think Taiwanese literature had its own characteristics and thought that even if there were any unique traits, they were remains from Japanese colonization, which should be neglected and even eradicated. For example, Tuo-Ying Luo used "enslavement" to describe the literary style during the Japanese rule period and thought that "nativist literature," dissociated from Chinese literature, was therefore of little worth.

.png) Kui Yang: During the Japanese colonization period, Taiwan's nature, politics, economy, and society changed enormously. But how much have Taiwanese people's emotions changed? This gap is extremely wide!

Kui Yang: During the Japanese colonization period, Taiwan's nature, politics, economy, and society changed enormously. But how much have Taiwanese people's emotions changed? This gap is extremely wide!On the other hand, the group of local writers, led by Kui Yang, did not claim that "Taiwanese literature must be independent from Chinese literature," but they opined that the uniqueness of Taiwan's history and society must be highlighted.

At the same time, they could not accept that the notion of "enslavement" completely negated the literary achievements during the Japanese rule period. They claimed that writers must understand and inherit the literary tradition from the Japanese rule period in order to truly understand the uniqueness of Taiwan and the special traits and needs of Taiwanese society. Mainland writers belittled the literary experience local writers gained from the colonial period, demonstrating the enormous gap between their views.

This heated debate seemed to give impetus to the rejuvenation of the literary scene. However, in 1949, the April 6th Incident erupted; Lei Ge, chief editor of Supplement Qiao, and Kui Yang, the main writer involved in the debate, were all arrested because of this political event. This literary debate that had significant potential was suppressed all of a sudden by political power.

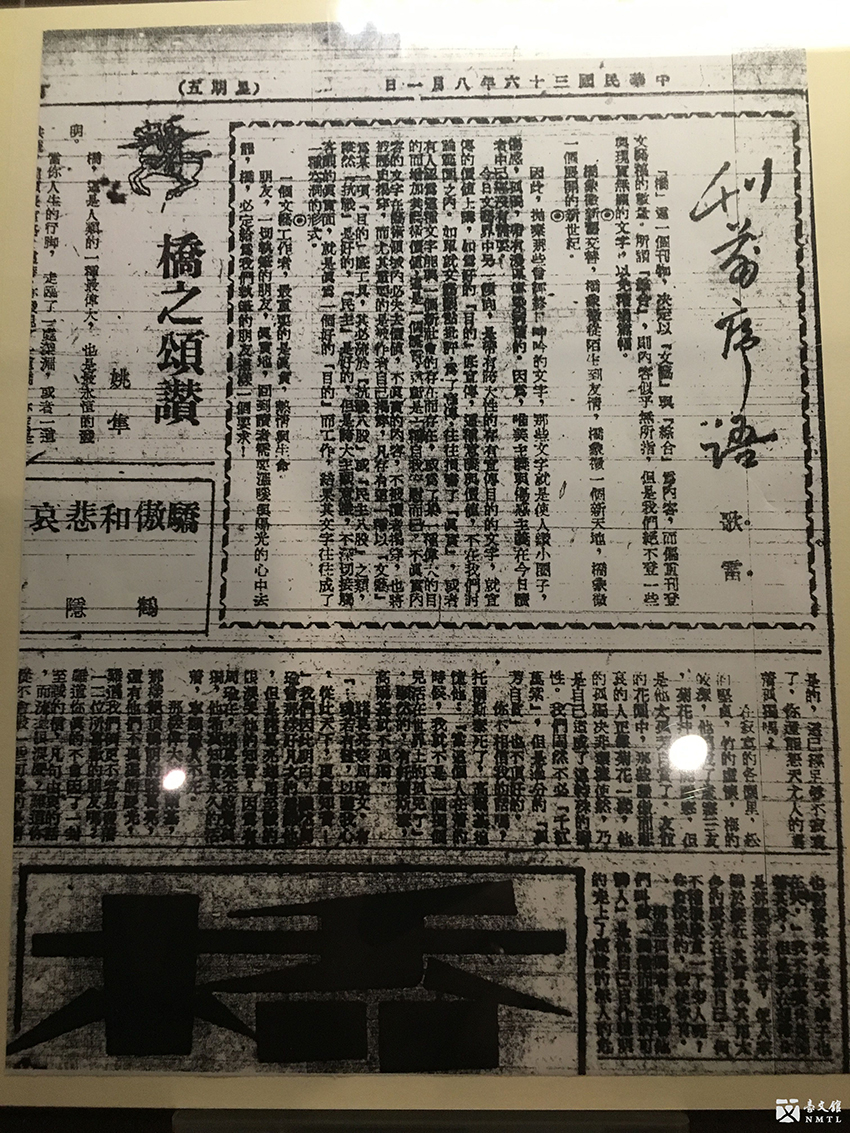

TAIWAN XINSHENG BAO Supplement Qiao

TAIWAN XINSHENG BAO added a supplement "Qiao (bridge)" on August 1, 1947. The editor in chief, Lei Ge, mentioned in the "Foreword Before Publication" that "Qiao" symbolizes "the transition from old to new," hoping to provide a place for dialogue between mainland and Taiwanese writers, as well as reconstructing Taiwanese literature after the war. At the same time, writers from different backgrounds, holding different opinions about "Taiwanese literature," engaged in the "Supplement Qiao Debate."