The overall beginning of Taiwanese New Literature Movement!

Taiwanese people wanted a new type of literature. However, the questions included: which writing system should be used for the new literature? Who were the target readers?

【The Main Argument】

Which language should one use to write for everyone? Which language should be spoken for everyone? Was "Write what you speak" a petty notion? Taiwan—Whose Taiwan was it?

The Japanese colonization period was a golden age for Taiwan's classical literature; however, it was also an era during which new-generation intellectuals could not bear the staleness of classical literature. The new intellectuals, who received a modern education, began "a debate on new and old literature" with the classical writers who inherited the literary tradition from the Qing dynasty. This phase marked the infancy of Taiwan's New Literature Movement.

In the late 1920s, due to the suppressive measures adopted by the Governor-General of Taiwan, many social movements were forced to stop. A number of intellectuals turned to focus on their works of literature. Consequently, the Taiwanese language movement and the nativist literature movement started, leading to a peak in the revolution of Taiwanese literature.

◎ 1924-1926 Debate over New and Old Literature: The sound of the era was about to change

Was classical literature the reason why the literary scene was dilapidated? Was it the broken-down ruins buried in the weeds? Wo-Jun Zhang, influenced by the May Fourth Movement, passionately raised questions that targeted writers of classical literature: Must literature continue to be so dull?

.png) Wo-Jun Zhang: Let's tear down the "ruins buried in the weeds" and build a new genre of literature!

Wo-Jun Zhang: Let's tear down the "ruins buried in the weeds" and build a new genre of literature!"The debate over new and old literature" was initiated by a group of young intellectuals, who reflected on the current status of Taiwan's literary scene and concluded that there must be literature reform and cultural rejuvenation.

The group espousing "new literature" was led by Wo-Jun Zhang, who went to China in 1921 and enrolled in the Department of Chinese Literature of Beijing Normal University. Inspired by the literature reform of the May Fourth Movement, he expressed his criticism of Taiwan's classical literature and considered it important to promote literature written in modern Chinese.

From 1924, like a fighter, he continuously published many articles that challenged classical literature . He opined that "old literature" diminished promising talents and sabotaged passionate young people. His claim was supported by Loa Ho and Xiao-Qian Cai.

The promotion of modern Chinese literature was not only a discussion on "which writing system should be used," but also presented a belief that "literature should be written for the people." Thus, instead of saying those young intellectuals were against classical literature, it would be more correct to say that they were against the aristocratic nature of classical literature and against the political calculations of "attracting old-generation literati with classical literature" made by the Japanese colonial government.

Heng Lian: You're only "picking up the leftovers of the West"!

Heng Lian: You're only "picking up the leftovers of the West"!The leader of the group for "old literature" was Heng Lian. Lian was considered one of the "three major poets in Taiwan during the Japanese colonial period." He undertook much effort for classical Chinese poems. During 1924, the year the debate erupted, he began publishing TAIWAN SHI HUI. Until October 1925, 22 issues were released. It was an important stronghold for classical literature.

Through publication, creation, and association, Heng Lian laboriously passed on classical Chinese literature. He emphasized the aesthetic function of literature, disagreed with that literature must be involved in reality and written for the public, and posited that the new literature promoted by Wo-Jun Zhang was only "picking up the leftovers of the western culture". "A frog in a well does not know the vastness of the ocean."

The members of the group also included Kun-Wu Zheng and Wen-Hu Huang.

What is worth noting is that though this debate led to the rise of Taiwan's new literature, it did not cause the decline of classical literature. During the Japanese colonial period, there were many classical poetry societies, which also had great influence on popular novels. The prosperity of the literary world was unprecedented. The results of the "debate over new and old literature" were not enough to "replace the old with the new"; instead, the new and old became two major themes that developed in parallel.

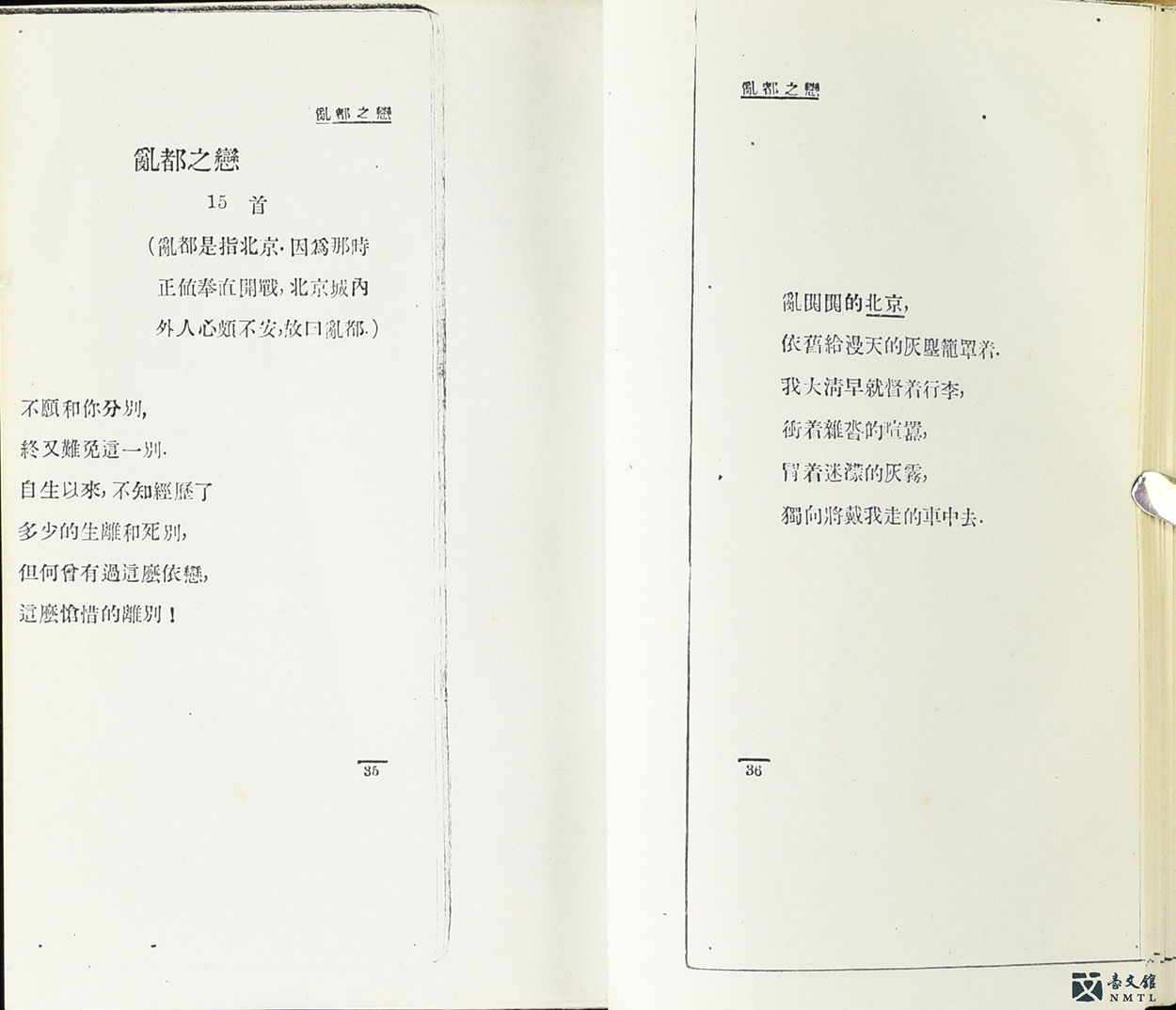

Wo-Jun Zhang, ROMANCE IN CITY OF CHAOS

In 1925, Wo-Jun Zhang published his ROMANCE IN CITY OF CHAOS in Taipei. It was the first collection of poems written in modern Chinese. "City of Chaos" refers to Beijing in the warlord era. The poems center on his romance with, and separation from, Wen-Shu Luo, his classmate at Beijing Normal University. Inspired by the May Fourth Movement (student protests), the writing style demonstrates his love of life and resentment against reality.(Donated by Ying-Zong Long, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

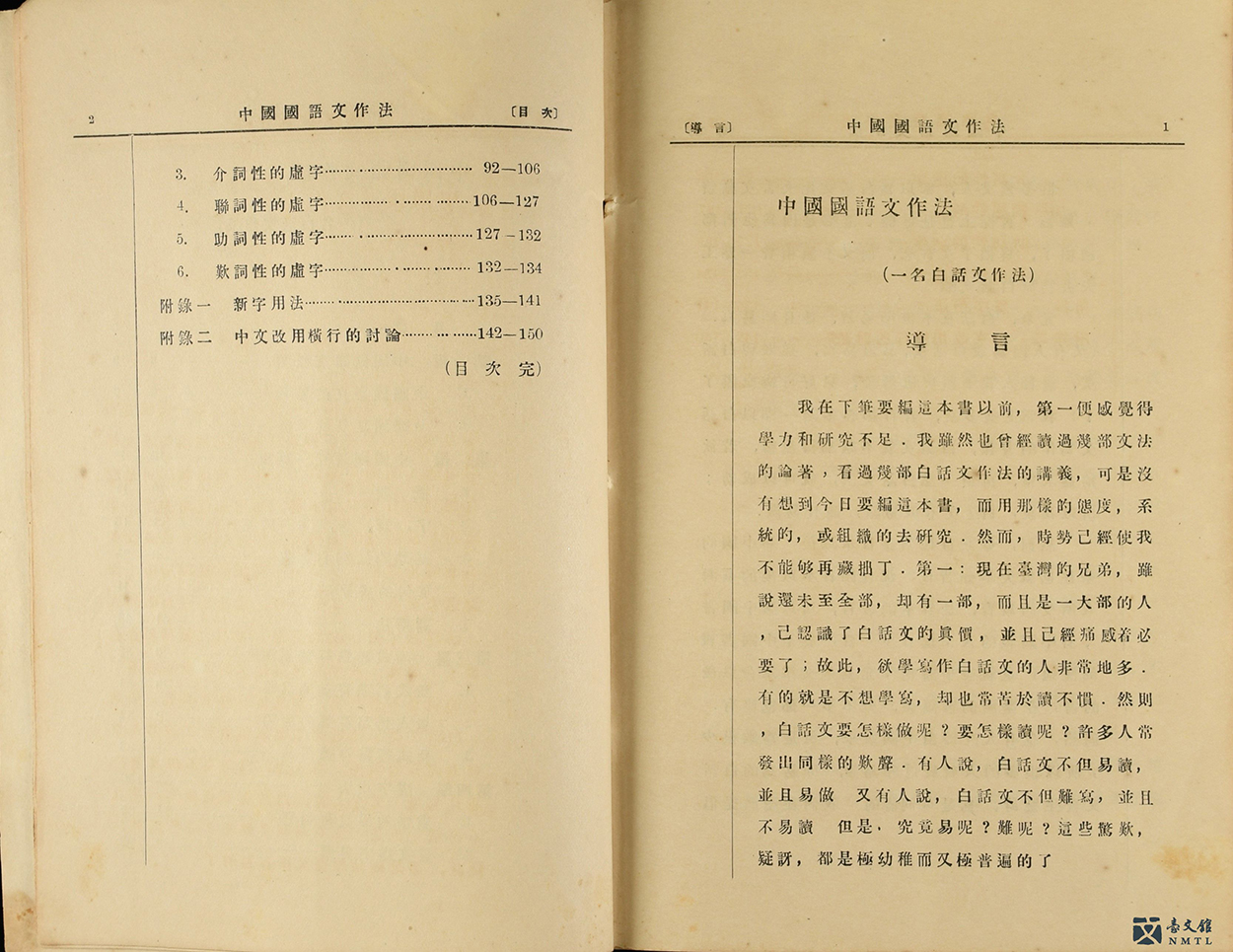

Wo-Jun Zhang, CHINESE WRITING

Also called MODERN CHINESE WRITING, the book was written by Wo-Jun Zhang in 1926. It was used as a course book for learning modern Chinese. The book is divided into three parts: "Definition of Modern Chinese", "Types of Chinese" and "Differentiation between Words and Sentences." The book covers an introduction to modern Chinese, grammar, punctuation marks, function words, and new words. The publication of this book manifests Zhang's effort in promoting modern Chinese. (Donated by Zi-Qian Huang, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

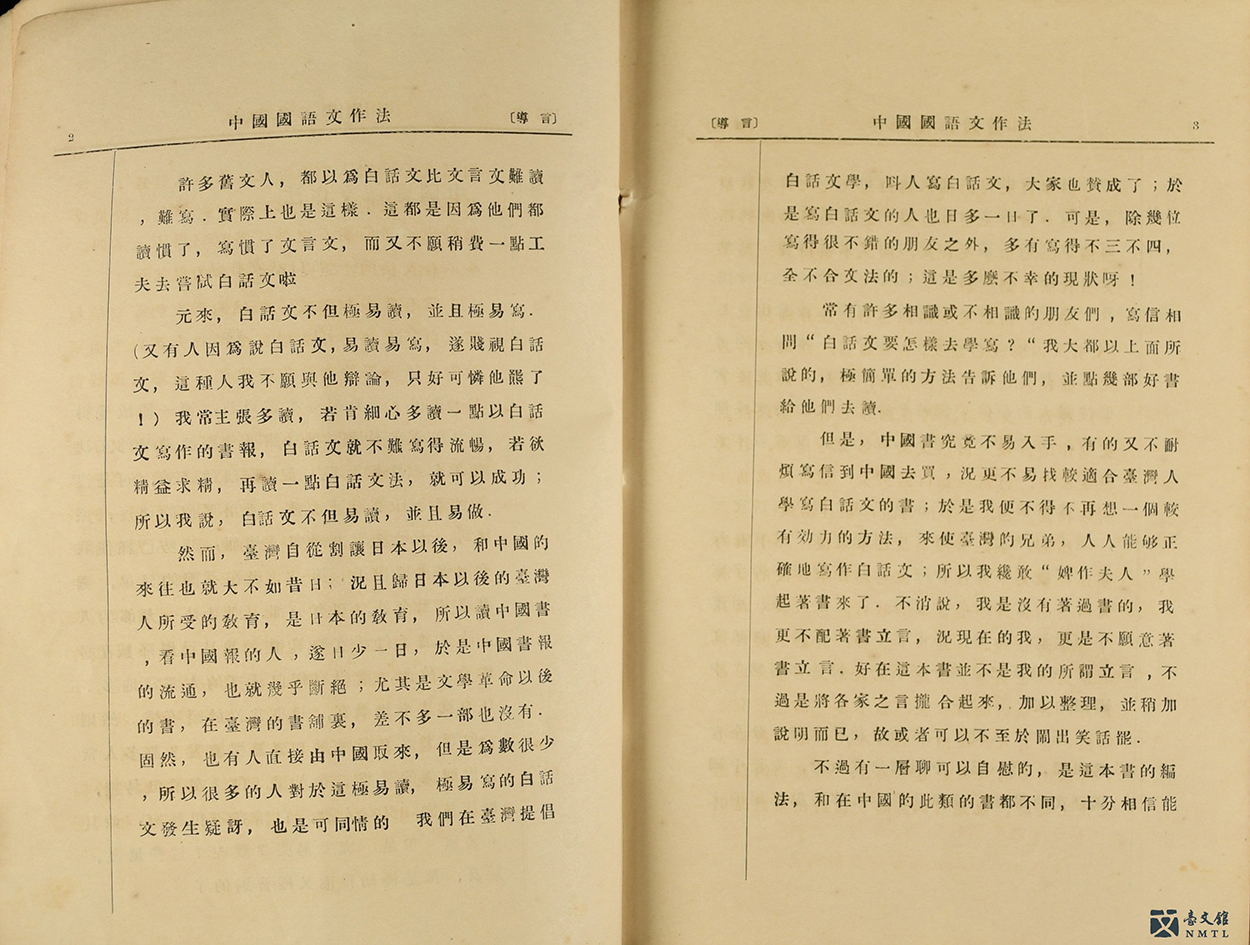

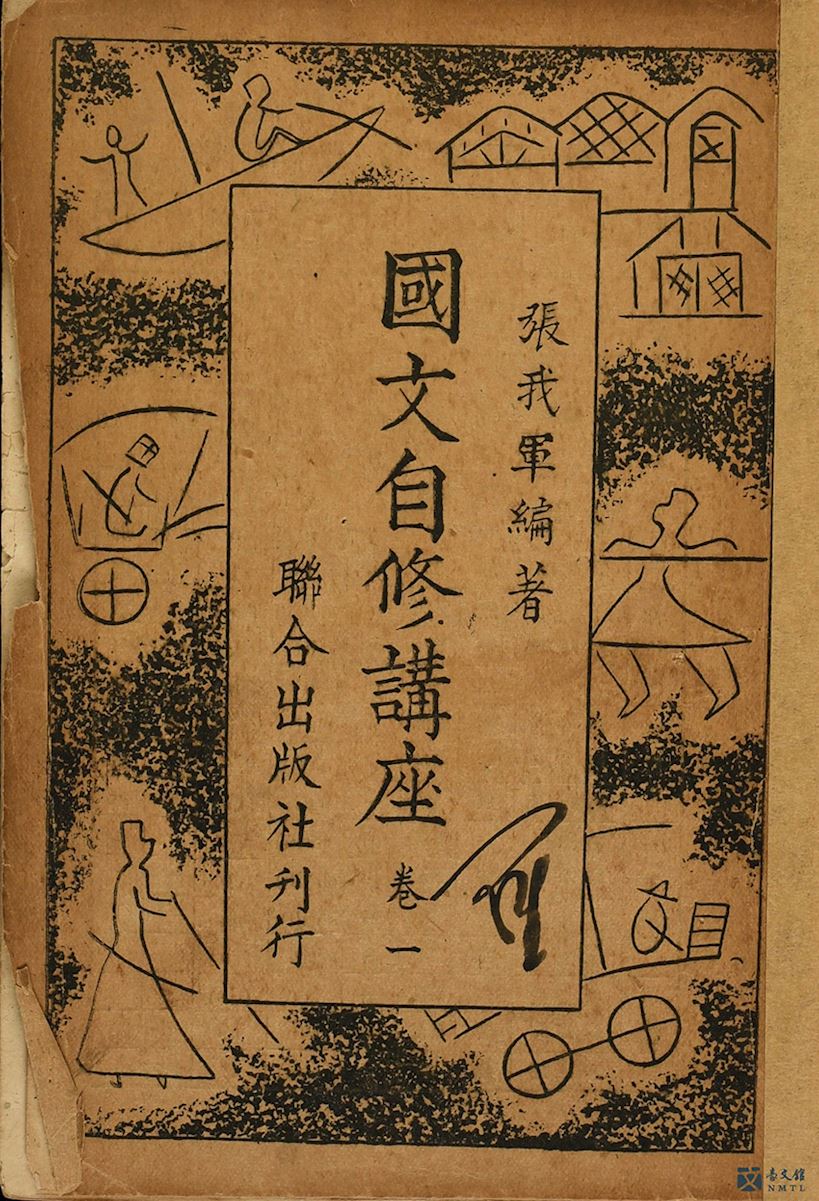

Wo-Jun Zhang, LEARN CHINESE BY SELF-STUDY Vol. 1

In 1947, Wo-Jun Zhang returned to Taiwan from China and acted as the director of the editing team of the Taiwan Education Association. There, he coordinated five volumes of LEARN CHINESE BY SELF-STUDY. The series features Chinese contemporary literary works, which were annotated with mandarin phonetic symbols by the editors. Also, in order to promote modern Chinese in Taiwan after the war, there were Japanese translations and explanations for Taiwanese readers who received Japanese education at the time. (Donated by Whose Books, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

.jpg)

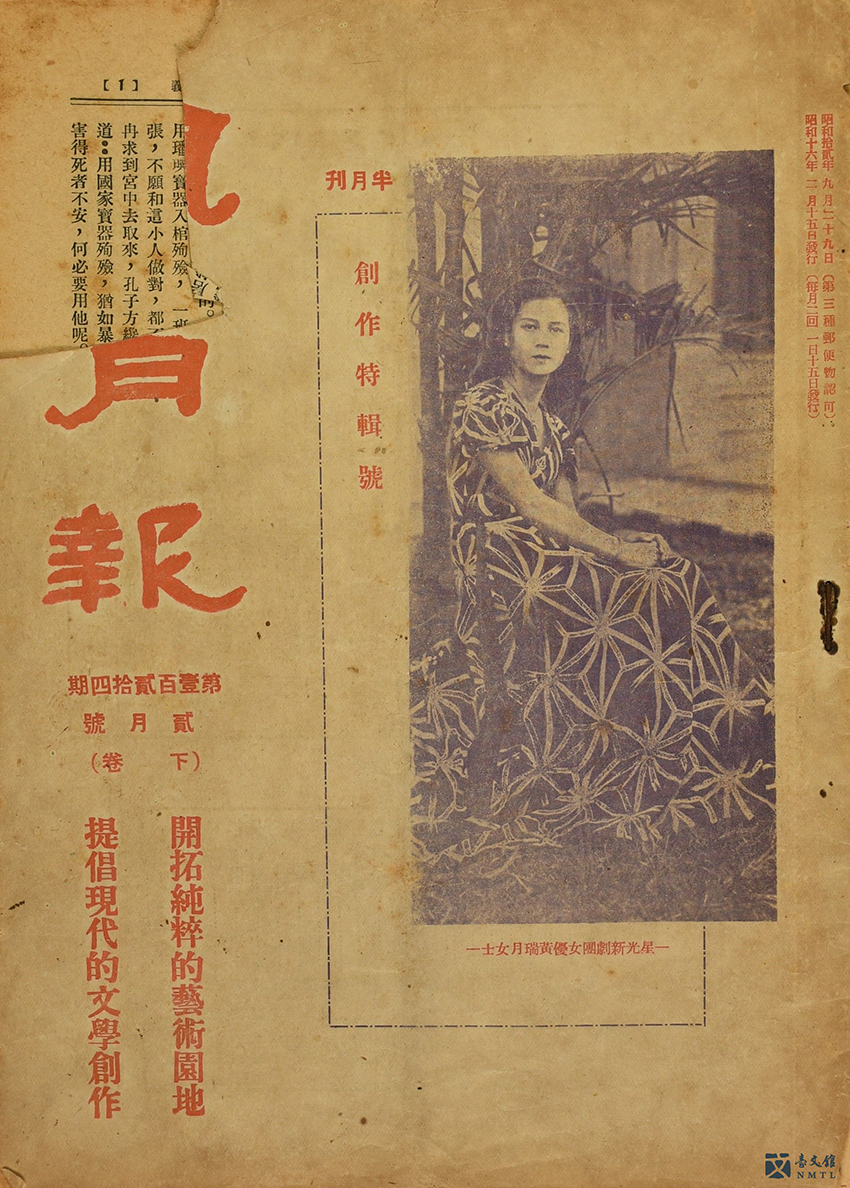

FENGYUE MAGAZINE Vol. 100 & 124

The debate over new and old literature continued in the 1940s, with writers still submitting their opinions on classical Chinese and modern Chinese to FENGYUE MAGAZINE and 369 XIAOBAO. Fengyue Magazine was a magazine dedicated to popular Chinese literature during the Japanese rule period. The magazine published many novels written in modern Chinese, showing the momentum for promoting modern Chinese in Taiwan's literary scene. (Donated by Ming-Yue Wu, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

.jpg)

SOUTH Vol. 166

In 1941, in response to Japan's southward expansion, FENGYUE MAGAZINE was renamed SOUTH. It was a platform where traditional writers and writers of popular literature could submit their works. Combining classical and modern literature, the publication accommodated both the refined and popular cultures. Meanwhile, it was a podium for the debate over new and old literature in the 1940s. (Donated by Mu-Chun Wei, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

De-Shi Huang, "Influence of May Fourth Movement on Taiwanese Literature"

This manuscript was written by De-Shi Huang in 1989, 70 years after the May Fourth Movement. The beginning of the article points out that though Taiwan was ruled by Japan, it was still deeply influenced by the May Fourth Movement in China. Examples include the promotion of modern Chinese in Taiwan by Chao-Qin Huang and Cheng-Chong Huang, the reform of Taiwan's modern literature by Wo-Jun Zhang, the novels written in modern Chinese by Loa Ho, and magazines that emerged due to the movement, such as SOUND OF SOUTH and TAIWAN LITERATURE. (Donated by De-Shi Huang, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

|

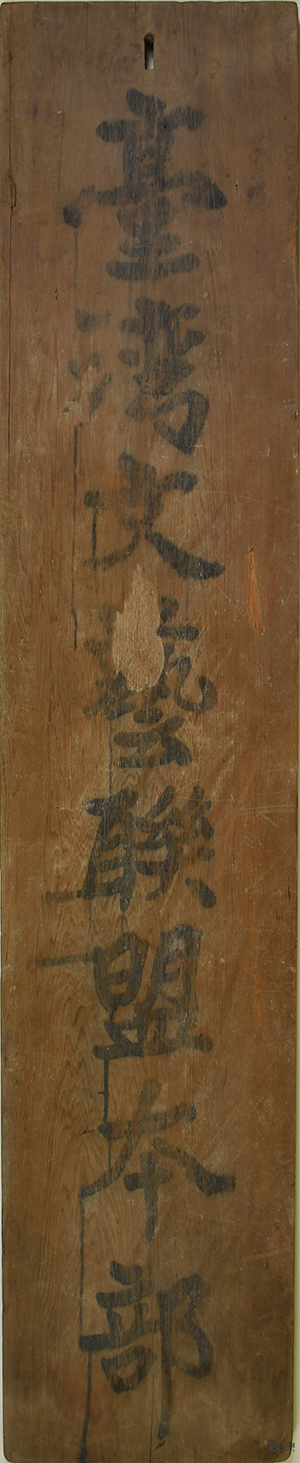

Wooden plate of "Headquarters of Taiwan Literature Alliance" In 1934, Shen-Qie Zhang, Ming-Hong Lai, and many others held the first national literature meeting in Taichung and announced the establishment of the "Taiwan Literature Alliance." This wooden plate was hung at the headquarters in Taichung. Later on, the alliance set up branches in Chiayi, Puli, Jiali, and Tokyo. Taiwan Literature Alliance not only overcame geographical boundaries, but also facilitated interaction among literary people with different stances and in various areas. (Donated by Sun-Yu Zhang, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature) |

◎ 1930-1934 Debate over Taiwanese: Fight for one's own voice

What should nativist literature be like? Could we read it out loud so that everyone could understand? Shi-Hui Huang eagerly challenged the literary scene. It was 1930, whenTaiwanese Literature Movement was flourishing. Strangely, though the new literature put an emphasis on writing for the public, the written language it used was the Chinese-style modern Chinese, which was unreadable for Taiwanese people. Should Taiwanese literature be closer to the language used by Taiwanese people? As intellectuals contemplated on how to communicate with the public, the idea of "popularization of literature" began to be heard among writers, leading to the "debate on literal Taiwanese."

.png) Shi-Hui Huang: Come and let's talk about nativism!

Shi-Hui Huang: Come and let's talk about nativism!If the "debate on new and old literature" ascertained the direction of writing in modern Chinese, then the "debate on literal Taiwanese" was one step forward: why were writers using Chinese-style modern Chinese to write about Taiwan? Could Taiwanese people write about their own land using their own language?

The person that started this debate was Shi-Hui Huang, who supported "literal Taiwanese." He wrote "The Importance of Promoting Nativist Literature" in 1930, sending shock waves across the literary scene. The words "you stand underneath Taiwan's sky and on Taiwan's soil" in his article have remained to this day the most famous manifesto in the history of Taiwanese literature.

Huang proposed "Nativist Literature," mainly referring to "literature written in Taiwanese." He hoped that literature could be closer to people's lives. This debate has been seen as the "first debate on nativism" in the history of Taiwanese literature.

Huang's claim was supported by Qiu-Sen Guo, Ho Loa, and Xiang-Zhang Li. The influence spread far, including Ho Loa's works, which incorporated more Taiwanese expressions.

Han-Chen Liao: Nativism? It is pastoral literature, and will be gone very fast.

Han-Chen Liao: Nativism? It is pastoral literature, and will be gone very fast.In contrast with "the debate on new and old literature", "the debate on literal Taiwanese" was more like a conflict within the "new literature" camp.

Han-Chen Liao, who was against "literal Taiwanese," opined that nativist literature paid too much attention to trivial local characteristics. These things would be gone very fast as time went by. He also raised a question to Huang: "If a place must have its own literature, taking into account the five Cho (prefectures) in Taiwan and 18 provinces in China, does it mean they all should have their own literature? "

Writers belonging to this camp included Ke-Fu Lin, Dian-Ren Zhu, Shi-Lang Wang, and Wo-Jun Zhang. The two opposing sides not only argued about "the uniqueness in Taiwanese literature" and "whether or not to emphasize Taiwan's uniqueness," but also inconspicuously showed the different interpretations of the same subject. "Who are the readers?" and "who are the fellow countrymen?" are often two sides of the same coin.

.png) Qiu-Sen Guo: All the illiterate people can serve the Japanese government, or learn words, or become tutors in their spare time.

Qiu-Sen Guo: All the illiterate people can serve the Japanese government, or learn words, or become tutors in their spare time. Qiu-Sen Guo was one of the writers who were the staunchest supporters of the "Taiwanese language" camp. He believed that literature was a tool for spreading ideas. Only by using the language that people could understand in writing could ideas be spread. He advocated using Chinese characters as the basis to transcribe Taiwanese and develop the new "literal Taiwanese."

After the debate ended, it seemed that no side had won. However, Guo later on founded the magazine SOUND OF SOUTH and wrote Taiwanese folk songs with Chinese characters. This attempt to textualize Taiwanese demonstrtaed the most concrete result of this debate.

Ke-Fu Lin: Use modern Chinese to write literature intelligible to Taiwanese and Chinese.

Ke-Fu Lin: Use modern Chinese to write literature intelligible to Taiwanese and Chinese.Lin belonged to the camp against literal Taiwanese. He claimed that it was unnecessary for Taiwan to be unique. Since Taiwan was closely associated with China, writers should just use words understandable to Taiwanese and Chinese.

The many writers of this camp all thought that the Chinese-style modern Chinese was a sufficient literary language, so there was no need to put any emphasis on literal Taiwanese. Meanwhile, they were also concerned that literal Taiwanese would set boundaries between Taiwanese literature and Chinese literature. This manifested that the two camps did not have the same opinion about "who the reader was" and should they focus on Taiwanese readers or Chinese readers?

In the following decades, the debate on "which language to be written" and "who the reader was" would repetitively appear in various forms.

.png)

Kun-Wu Zheng, "Airs of the States of Taiwan" in TAIWAN'S ART REALM, One Volume Edition

In 1927, Kun-wu Zheng compiled Taiwanese folk poetry in TAIWAN'S ART REALM and named them "Airs of the States in Taiwan." All the poems have the same seven-syllable and four-line form. When collecting these poems, Zheng added annotations and explanations, creating unique values for the vernacular Chinese literature in Taiwan. (Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

.jpg)

369 XIAOBAO Vol. 476

Founded in 1930, 369 XIAOBAO (small publication) was released on the 3rd, 6th, and 9th every month. It was a Chinese-language journal during the Japanese rule period and featured works written in both classical and modern Chinese, including popular novels, news stories, and interesting facts. Covering a wide variety of topics, it targeted both educated readers and laymen. The tone of the newspaper was in contrast to the seriousness of "big newspapers"; instead, the name suggested its "joviality". (Donated by Xin-Yi Su, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

NEW TAIWANESE LITERATURE No. 5, Vol. 2, First Issue

In the 1930s, NEW TAIWANESE LITERATURE held a handful of symposiums. With "expectations for new Taiwanese literature" as the theme, the development of colonial literature was discussed, as Taiwanese editors engaged in dialogue with writers. In addition, there was a "reflection and goals" session, where attendees talked about their views on "New Taiwanese Literature Movement" and "the development of Taiwanese literature." Shi-Lang Wang and Han-Chen Liao both mentioned that the reason why the literary scene was dull at the time was the lack of publications by Taiwanese writers; Taiwanese literature's uniqueness relied on its textualization in Chinese. (Donated by Ying-Zong Long, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

SOUND OF SOUTH First Issue

In 1932, SOUND OF SOUTH was published as a bimonthly magazine. Founded by Chun-Cheng Huang, the publication was also joined by Rong-Zhong Ye and Qiu-Sen Guo. After the 12th issue, it was banned by the government. Apart from accepting submissions, SOUND OF SOUTH was also a place of discussion and implementation regarding the debate over the textualization of the Taiwanese language. Fu-Ren's "The Heterogeneous Taiwanese" and Qiu-Sen Guo's "Mapping of Taiwanese and Written Chinese" were both important articles at the time. (Donated by Ying-Zong Long, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

.jpg)

TAIWAN LITERATURE First Issue

It was Taiwan Literature Alliance's official publication published by Taichung Central Bookstore. Shenqie Zhang thought this publication ought to be established based on Taiwan's "authenticity" and reflect the notion of "popularization of literature" espoused by intellectuals. Among all the literary magazines founded by Taiwanese people during the Japanese period, TAIWAN LITERATURE was the longest lasting and featured the most writers. (Donated by De-Shi Huang, Collection of National Museum of Taiwan Literature)

.jpg)